David Bronstein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids David Bronstein |

|

|---|---|

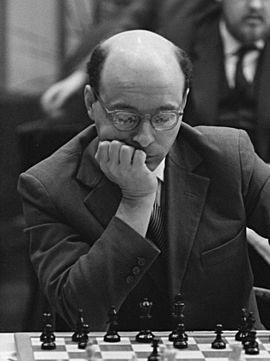

Bronstein in 1968

|

|

| Full name | Дави́д Ио́нович Бронште́йн David Ionovich Bronstein |

| Country | Soviet Union → Russia |

| Born | February 19, 1924 Bila Tserkva, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | December 5, 2006 (aged 82) Minsk, Belarus |

| Title | Grandmaster (1950) |

| Peak rating | 2595 (May 1974) |

David Ionovich Bronstein (Russian: Дави́д Ио́нович Бронште́йн; born February 19, 1924 – died December 5, 2006) was a famous chess player from the Soviet Union and Ukraine. He became an International Grandmaster in 1950, which is the highest title a chess player can get. David Bronstein almost became World Chess Champion in 1951, missing it by a tiny bit.

He was one of the strongest players in the world from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s. Other chess players called him a creative genius and a master of clever moves. He was also a well-known chess writer. His book Zurich International Chess Tournament 1953 is thought to be one of the best chess books ever written.

Contents

Early Life

David Bronstein was born in Bila Tserkva, a city in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the Soviet Union. He came from a family that didn't have much money. He learned to play chess at age six from his grandfather.

When he was a teenager in Kyiv, a famous chess teacher named Alexander Konstantinopolsky helped him improve his game. At just 15 years old, David finished second in the Kyiv Championship. The next year, at 16, he earned the Soviet Master title by placing second in the 1940 Ukrainian Chess Championship. He became very good friends with the winner, Isaac Boleslavsky, and later married Boleslavsky's daughter, Tatiana, in 1984.

After finishing high school in 1941, David planned to study mathematics at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. However, his plans were stopped because World War II spread across eastern Europe. He had started playing in a big Soviet Championship event, but it was canceled when the war began. After the war ended, he studied for about a year at the Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University.

David was not allowed to join the military during the war. Instead, he worked different jobs, like helping to rebuild buildings damaged by the war. During this time, his father, Johonon, faced difficulties and was unfairly held for several years.

Becoming a Grandmaster

As the war ended and the Soviet Union was winning against the invaders, David Bronstein could play competitive chess again. His first big Soviet tournament was the 1944 USSR Chess Championship. In that event, he won a game against Mikhail Botvinnik, who would soon become the world champion.

Bronstein moved to Moscow as the war finished. He was seen as a promising young player, but he quickly became much stronger. He placed third in the 1945 USSR Championship. This result earned him a spot on the Soviet team. He won both his games in the famous 1945 USA vs. USSR radio chess match, helping the Soviet team win. He then played well in other team matches, showing he belonged among the best Soviet chess players. Bronstein tied for first place in the Soviet Championships in both 1948 and 1949.

Challenging for the World Title

Bronstein's first big international win was at the 1948 Saltsjöbaden Interzonal tournament, which he won. This win allowed him to play in the Candidates' Tournament in 1950 in Budapest. He earned his Grandmaster title in 1950 when FIDE, the World Chess Federation, officially gave out the title. Bronstein won the Candidates' Tournament by beating his friend Isaac Boleslavsky in a playoff match in Moscow in 1950.

Between 1945 and 1950, Bronstein improved incredibly fast, leading him to challenge for the World Chess Championship in 1951.

1951 World Championship Match

Many people believe David Bronstein is one of the greatest players who never won the World Championship. He came very close in the 1951 World Championship match against Mikhail Botvinnik, who was the champion. The match ended in a 12–12 tie. Each player won five games, and 14 games were drawn.

The lead in the match changed many times. Both players tried out different opening moves, and almost every game was exciting and played with great effort. Bronstein often used Botvinnik's favorite opening moves, which seemed to surprise the champion. Botvinnik had not played in competitive games for three years since winning the title in 1948. Both players showed very high-quality chess. Bronstein won four of his five games with clever combinations of moves. He was ahead by one point with two games left, but he lost the 23rd game and drew the last game. Because of FIDE rules, the champion kept the title if the match was a tie. Bronstein never got this close to the title again.

Botvinnik later said that Bronstein didn't win because he wasn't as strong in the endgame (the final part of a chess game) and in simple positions.

1953 Candidates Tournament

Bronstein played well at the 1953 Candidates Tournament in Switzerland. He finished tied for second place with Paul Keres and Samuel Reshevsky, two points behind the winner, Vasily Smyslov. Bronstein's book about this tournament is considered a classic.

Chess Career After 1953

His result in the 1953 Candidates Tournament allowed him to play directly in the 1955 Gothenburg Interzonal, which he won without losing a single game. From there, he went to another close call at the 1956 Candidates' tournament in Amsterdam. He tied for third place, behind the winner Smyslov and second-place Keres.

Bronstein had to qualify for the 1958 Interzonal by placing third at the USSR Championship in Riga in 1958. At the 1958 Interzonal in Portorož, Bronstein was expected to win. However, he missed qualifying for the next stage by just half a point. He lost a game in the last round to a weaker player, Rodolfo Tan Cardoso, when the power went out during the game because of a thunderstorm. Bronstein said he couldn't focus after that. He also missed qualifying for the 1962 cycle. At the Amsterdam 1964 Interzonal, Bronstein played very well, but only three Soviet players could move on because of a FIDE rule. He finished behind his countrymen Smyslov, Mikhail Tal, and Boris Spassky. His last Interzonal was in 1973, when he was 49 years old, and he finished sixth.

Bronstein won many first prizes in tournaments. Some of his most important wins were the Soviet Chess Championships in 1948 (tied with Alexander Kotov) and 1949 (tied with Smyslov). He also tied for second place in the Soviet Championships in 1957 and 1964–65. He tied for first with Mark Taimanov at the World Students' Championship in 1952. Bronstein also won the Moscow Championships six times. He played for the USSR at the Olympiads in 1952, 1954, 1956, and 1958. He won prizes for his performance on his board in each of these events, losing only one of his 49 games. He also won four team gold medals at the Olympiads. In a 1954 team match against the USA, Bronstein won all four of his games, which is very rare at such a high level.

He also won major tournaments in Hastings (1953–54), Belgrade (1954), Gotha (1957), Moscow (1959), Szombathely (1966), East Berlin (1968), Dnepropetrovsk (1970), Sarajevo (1971), Sandomierz (1976), Iwonicz Zdrój (1976), Budapest (1977), and Jūrmala (1978).

Legacy and Later Years

David Bronstein wrote many chess books and articles. He also had a regular chess column in the Soviet newspaper Izvestia for many years. He is especially known for his book Zurich International Chess Tournament 1953. This book sold many copies in the USSR and is considered one of the best chess books ever. Later, he co-wrote his autobiography, The Sorcerer's Apprentice (1995), with his friend Tom Fürstenberg. Both books are important in chess history. Bronstein wanted to explain the ideas behind the players' moves, rather than just showing long lists of moves.

Bronstein loved to play the rarely seen King's Gambit in top-level games, showing his creative style. He also helped make the King's Indian Defence a popular and important opening. This is shown in his contribution to the 1999 book Bronstein on the King's Indian. Throughout his long career, Bronstein used a very wide variety of chess openings.

Two chess variations are named after him. In the Caro-Kann Defence, there is the Bronstein–Larsen Variation. In the Scandinavian Defence, there is the Bronstein Variation.

Bronstein refused to sign a letter that criticized Viktor Korchnoi when Korchnoi left the Soviet Union in 1976. Because of this, Bronstein's state-paid chess salary was stopped, and he was not allowed to play in major tournaments for over a year. He was mostly banned from high-level events for several years in the mid-1980s.

Bronstein was a forward-thinking chess player. He was one of the first to suggest making competitive chess faster. In 1973, he came up with the idea of adding a small amount of extra time for each move a player makes. This idea has become very popular and is used on almost all digital chess clocks today. He also enjoyed playing against computer chess programs and usually did well.

Bronstein liked to try out unusual and less common openings, like the King's Gambit and Latvian Gambit. However, he usually didn't use them in very serious games. Like most grandmasters from the 1950s and 1960s, he preferred e4 openings, especially the Ruy Lopez, French Defence, and Sicilian Defence. Even though he knew a lot about openings, his endgame skills were sometimes considered less strong.

In his later years, Bronstein continued to play in tournaments, often in Western Europe after the Soviet Union broke up. He kept playing at a very good level, even tying for first place at the Hastings Swiss in 1994–95 when he was 70 years old. He wrote several important chess books and inspired many people with his friendly attitude and stories about his rich chess history. David Bronstein passed away on December 5, 2006, in Minsk, Belarus, due to problems from high blood pressure.

His last book, Secret Notes, was almost finished when he died and was published in 2007. In the introduction, Garry Kasparov, a big fan of Bronstein's chess, wrote that he believed Bronstein should have won the 1951 match against Botvinnik based on his play.

Best Combination

| This section uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves. |

During the 1962 Moscow vs. Leningrad Match, Bronstein played on the top board for the Moscow team. Playing with the white pieces, he beat Viktor Korchnoi in a game that ended with a tactic he called "one of the best combinations in my life, if not the best."

- 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0-0 Nxe4 6.d4 b5 7.Bb3 d5 8.dxe5 Be6 9.c3 Be7 10.Bc2 0-0 11.Qe2 f5 12.exf6 Bxf6 13.Nbd2 Bf5 14.Nxe4 Bxe4 15.Bxe4 dxe4 16.Qxe4 Qd7 17.Bf4 Rae8 18.Qc2 Bh4 19.Bg3 Bxg3 20.hxg3 Ne5 21.Nxe5 Rxe5 22.Rfe1 Rd5 23.Rad1 c5 24.a4 Rd8 25.Rxd5 Qxd5 26.axb5 axb5 27.Qe2 b4 28.cxb4 cxb4 29.Qg4 b3 30.Kh2 Qf7 31.Qg5 Rd7 32.f3 h6 33.Qe3 Rd8 34.g4 Kh8 35.Qb6 Rd2 36.Qb8+ Kh7 37.Re8 Qxf3 38.Rh8+ Kg6 39.Rxh6+ (diagram)

- Bronstein:

- 1–0

Notable Games

- Sergei Belavenets vs. Bronstein, USSR Championship semifinal, Rostov-on-Don 1941, King's Indian Defence, Fianchetto Variation (E67), 0–1 A 17-year-old Bronstein plays against the head of the USSR Classification Committee.

- Ludek Pachman vs. Bronstein, tt Prague 1946, King's Indian Defence, Fianchetto Variation (E67), 0–1 A surprising and clever attack that was praised around the world.

- Bronstein vs. Isaac Boleslavsky, Candidates' Playoff Match, Moscow 1950, game 1, Grunfeld Defence (D89), 1–0 Bronstein makes a smart sacrifice that leads to a beautiful win.

- Mikhail Botvinnik vs. Bronstein, World Championship Match, Moscow 1951, Nimzo-Indian Defence, Rubinstein Variation (E47), 0–1 Bronstein beats Botvinnik with the black pieces in their 1951 World Championship match.

- Bronstein vs. Mikhail Botvinnik, World Championship Match, Moscow 1951, game 22, Dutch Defence, Stonewall Variation (A91), 1–0 A very deep combination of moves helps Bronstein win and take the lead in the match.

- Samuel Reshevsky vs. Bronstein, Zurich Candidates' 1953, King's Indian, Fianchetto Variation (E68), 0–1 This game was chosen by Grandmaster Ulf Andersson as his favorite game by another player.

- Bronstein vs. Paul Keres, Goteborg Interzonal 1955, Nimzo-Indian Defence, Rubinstein Variation (E41), 1–0 An exciting game between two attacking geniuses.

- Itzak Aloni vs. Bronstein, Moscow Olympiad 1956, King's Indian Defence, Saemisch Variation (E85), 0–1 Bronstein sacrifices three pawns to open lines and attack Aloni's king.

- Bronstein vs. M-20(Computer), Moscow Mathematics Institute 1963, King's Gambit: Accepted, Schallop Defense (C34), 1–0 This is the oldest known game between a grandmaster and a computer.

- Stefan Brzozka vs. Bronstein, USSR 1963, Dutch Defence, Leningrad Variation (A88), 0–1 A surprising and deep move that breaks through White's position.

- Lev Polugaevsky vs. Bronstein, USSR 1971, English Opening, Symmetrical Variation (A34), 0–1 Bronstein offers a clever pawn sacrifice that leaves his opponent stuck.

- Bronstein vs. Ljubomir Ljubojevic, Petropolis Interzonal 1973, Alekhine's Defence, Four Pawns' Attack (B03), 1–0 A long-range rook sacrifice helps him win the game in a brilliant way.

- Bronstein vs. Viktor Kupreichik, USSR Championship semifinal, Minsk 1983, King's Indian Defence (E90), 1–0 The experienced master Bronstein shows a younger player some tricks in the King's Indian.

- Bronstein vs. Ivan Sokolov, Pancevo 1987, Grunfeld Defence, Russian Variation (D98), 1–0 Another young master experiences Bronstein's strong chess skills.

- Stuart Conquest vs. Bronstein, London 1989, CaroKann Defence (B10), 0–1 A dazzling display of tactics leaves White unable to do anything in just 26 moves.

- Bronstein vs. Walter Browne, Reykjavik 1990, Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation (B99), 1–0 Bronstein comes up with new ideas in a very deep opening, and even a top player like Browne can't find a way to win.

Books

- The Chess Struggle in Practice: Lessons from the Famous Zurich Candidates Tournament of 1953, 1978

- 200 Open Games, 1991

- The Modern Chess Self-Tutor, 1995

- The Sorcerer's Apprentice, 1995

- Bronstein on the King's Indian, 1999

- Secret Notes, 2007

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: David Bronstein para niños

In Spanish: David Bronstein para niños

- Game clock – for the Bronstein delay

- List of Jewish chess players

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |