Downtown Eastside facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Downtown Eastside

|

|

|---|---|

|

Neighbourhood

|

|

View of the Downtown Eastside and Woodward's site at dusk from Harbour Centre in summer 2018.

|

|

| Nicknames:

DTES, Skid Row

|

|

| Country | Canada |

| Province | BC/BCE |

| City | Vancouver |

| Population

(2011)

|

|

| • Total | 18,477 for the greater DTES area |

| • Estimate

(2009)

|

6,000 – 8,000 for the DTES |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| Postal code |

V6A

|

| Area code(s) | 604, 778, 236 |

The Downtown Eastside (DTES) is a neighbourhood in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. It is one of the city's oldest areas. The DTES faces some big challenges like homelessness, poverty, and many people needing extra support for their mental health.

However, it is also known for its strong sense of community resilience, a history of people working together for change, and many artistic contributions.

Around the early 1900s, the DTES was the main hub of Vancouver. It was the center for politics, culture, and shopping. Over many years, the city's main area slowly moved west. The DTES then became a poorer, but still quite stable, neighbourhood.

In the 1980s, the area began to decline quickly. This was partly because the government stopped funding affordable social housing. As of 2018, key issues include old and run-down homes, not enough affordable places to live, and many people needing help with their mental health.

About 7,000 people are estimated to live in the DTES. Compared to the rest of Vancouver, the DTES has more men and adults who live alone. It also has many more Indigenous Canadians, who are often affected more by the neighbourhood's social problems.

Since Vancouver's real estate prices started to boom in the early 2000s, the area has seen more gentrification. This means new, more expensive buildings are being built. Some people think gentrification helps renew the city. Others believe it leads to more people losing their homes and becoming homeless.

Many efforts have been made to improve the DTES. By 2009, over $1.4 billion had been spent. Services in the wider DTES area cost about $360 million each year. People from different political views say that little progress has been made overall. However, there are many individual success stories.

Ideas to help the area include investing more in social housing, improving care for people with mental health needs, spreading services out more across the city, and better coordinating these services. But the city, province, and federal governments do not fully agree on long-term plans for the area.

Contents

Understanding the Downtown Eastside

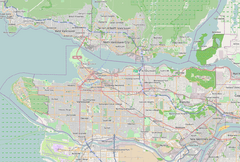

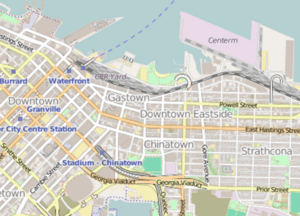

Where is the DTES Located?

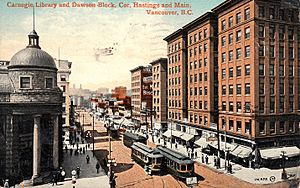

The "Downtown Eastside" usually refers to an area about 10 to 50 blocks in size. It is a few blocks east of Vancouver's main Downtown business area. The neighbourhood centers around the intersection of Main Street and Hastings Street. People have gathered here for over a hundred years.

The Carnegie Community Centre is also located at this intersection. The area around Hastings and Main is where the neighbourhood's social challenges are most visible.

What are the DTES Boundaries?

The exact borders of the DTES can change and are not always clear. Here are some ways people describe its boundaries:

- A 2016 study looked at an area of six blocks along Hastings and Cordova Streets. This was between Cambie Street and Jackson Avenue.

- The City of Vancouver describes a "Community-based Development Area." This is where important places for low-income residents are found. It includes Hastings Street from Abbott Street to Heatley Avenue, and the blocks around Oppenheimer Park.

- Some definitions say the DTES extends along Main Street past Terminal Avenue. It can also include land next to Vancouver's port.

The Greater DTES Area

For planning and statistics, the City of Vancouver uses "Downtown Eastside" for a much larger area. This greater DTES area includes places like Chinatown, Gastown, Strathcona, and the Victory Square area. It also has a light industrial area to the north.

This larger area is bordered by Richards Street to the west and Clark Drive to the east. To the north are Waterfront Road and Water Street. Various streets like Malkin Avenue and Prior Street form the southern border. The greater DTES area has popular tourist spots. It also has almost 20% of Vancouver's historic buildings.

A Look Back: History of the DTES

Early Days and Growth

The DTES is part of the traditional lands of the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh, and Musqueam First Nations. European settlers arrived in the mid-1800s. Most early buildings were destroyed in the Great Vancouver Fire of 1886.

Residents rebuilt their town near Burrard Inlet. This area now includes Gastown and part of the DTES. Around 1900, the DTES was the city's center. It had the city hall, courthouse, banks, and main shops. The Carnegie Library was also there.

Hundreds of hotels and rooming houses served travelers. These travelers connected between Pacific steamships and the Canadian Pacific Railway. Large Japanese and Chinese immigrant communities settled in Japantown and Chinatown.

The Great Depression and Changes

During the Depression, many men came to Vancouver looking for work. Most went home later. But injured, sick, or elderly workers stayed. They remained in the DTES area, then called Skid Road. It became an affordable place to live as Vancouver's main downtown moved west.

In 1942, the Canadian government forced all ethnic Japanese people to leave. This included 8,000 to 10,000 people from the DTES. Most did not return to the once-busy Japantown after the war.

In the 1950s, the city center kept moving west. The interurban rail line closed, and its main station was at Carrall and Hastings. Theatres and shops moved towards Granville and Robson streets. As fewer tourists came, the neighbourhood's hotels became run-down. They were slowly turned into single room occupancy (SRO) housing, which is still used today.

The 1980s: New Challenges

In the early 1980s, the DTES was a lively but calm place. Things started to change before Expo 86. About 800 to 1,000 people living in DTES hotels were asked to leave to make room for tourists.

At the same time, the provincial government changed its policy for people with mental health issues. Patients from Riverview Hospital were sent home. The promise was that they would get support in their communities. But between 1985 and 1999, the number of days people spent in B.C. psychiatric hospitals dropped by almost 65%. Many of these people moved to the DTES. They were drawn by the accepting culture and low-cost housing. But they struggled without enough treatment and support.

From the 1990s to Today

In the 1990s, the DTES faced even more difficulties. Woodward's, a large department store on West Hastings street, closed in 1993. This greatly affected the once-busy shopping area. Also, a crisis in housing and homelessness began.

Between 1970 and the late 1990s, the number of low-income homes in the DTES and other parts of the city decreased. This was partly because buildings were turned into more expensive condos or hotels. In 1993, the federal government stopped funding social housing. The rate of building social housing in B.C. dropped by two-thirds, even though more people needed it.

By 1995, reports showed homeless people sleeping in parks and abandoned buildings. Cuts to the provincial welfare program in 2002 made things even harder for poor and homeless people. Across the city, the number of homeless people grew from 630 in 2002 to 1,300 in 2005.

In the 2000s, a lot of money was invested in DTES services and buildings. This included redeveloping the Woodward's Building. The provincial government also bought 23 SRO hotels to turn them into social housing. In 2009, The Globe and Mail estimated that governments and private companies had spent over $1.4 billion since 2000. These projects aimed to solve the area's many problems.

Opinions differ on whether the area has improved. A 2014 article in the National Post said, "For all the money and attention here, there is little success at either getting the area's shattered populace back on their feet, or cleaning up the neighbourhood." Former NDP premier Mike Harcourt called the current situation "100-per-cent failure." However, in 2014, B.C. housing minister Rich Coleman said, "I’ll go down for a walk in the Downtown Eastside, night time or day time, and it's dramatically different than it was. It's incredibly better than it was five, six years ago."

Who Lives in the DTES?

Population Numbers

There are no official numbers for the DTES population. Estimates range from 6,000 to 8,000 people.

Official numbers are available for the wider DTES area. In 2011, about 18,477 people lived there. Compared to Vancouver as a whole, the wider DTES had more males (60% vs. 50%) and more seniors (22% vs 13%). It had fewer children and youth (10% vs 18%) and slightly fewer immigrants. It also had more Indigenous Canadians (10% vs. 2%).

A 2009 study looked at an area of just over 30 city blocks in and around the DTES. It showed that 14% of residents were of Indigenous background. The average household size was 1.3 residents, and 82% of people lived alone. Children and teenagers made up 7% of the population, compared to 25% for Canada overall.

People living in single room occupancy (SRO) hotels in the wider DTES area are often studied. A 2013 survey found that 77% of this group were male. Their average age was 44. Indigenous people made up 28% of this group, and Europeans 59%.

Culture and Community in the DTES

Many people from outside the DTES might feel worried about the area. But its residents are proud of their neighbourhood. They say it has many good things. DTES residents describe a strong sense of community and rich cultural history. They say their neighbours are accepting and understanding of people with health issues.

According to the city government, Hastings Street is important to SRO residents. It is "a place to meet friends, get support, access services and feel like they belong."

Community Activism and Art

The area has a strong history of supporting its residents who face challenges. This goes back to at least the 1970s. That is when the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA) was formed. Over the years, the DTES community has often pushed back against efforts to "clean up" the neighbourhood. They resist plans that would break up their close-knit community.

Successful efforts led by residents to improve the DTES include:

- Turning the closed Carnegie Library into a community center in 1980.

- Opening a supervised injection site in 2003, which led to the creation of Insite.

- Improvements to Oppenheimer Park.

- Creating CRAB Park.

In 2010, the V6A postal area, which includes most of the DTES, had the second-highest number of artists in the city. Artists made up 4.4% of the workforce there. This is compared to 2.3% in Vancouver as a whole. The Downtown Eastside Artists' Collective is one example of an art group.

The wider DTES area has several art galleries, artist-run centers, and studios. Important local artists include poet Henry Doyle, artist Marcel Mousseau, and poet Bud Osborn.

Festivals and Performances

Notable yearly events include the Downtown Eastside Heart of the City Festival. This festival shows off the neighbourhood's art, culture, and history. The Powell Street Festival in Oppenheimer Park celebrates Japanese-Canadian arts and culture.

The Smilin' Buddha Cabaret operated from 1952 to the late 1980s. It was a symbol of "cultural vitality" at 109 East Hastings Street. It showed how the neighbourhood itself was changing. City Opera of Vancouver, the Dancing on the Edge Festival, and other artists often perform in DTES places. These include the Carnegie Centre, the Firehall Arts Centre, and the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts at the Woodward's site.

In 2010, Sam Sullivan, a former mayor of Vancouver, said about the DTES: "Behind the visible people who clearly have a lot of troubles, there's a community. Some very intelligent people say this is the cultural heart of the city."

Current Challenges in the DTES

Mental Health Support

The DTES population has very high rates of people needing mental health support. In 2007, Vancouver Coastal Health estimated that 2,100 DTES residents "exhibit behaviour that is outside the norm." These people need more health service support.

According to the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) in 2008, up to 500 of these people had "extreme behaviours, no permanent housing and regular police contact." The VPD reported in 2008 that in its district, which includes the Downtown Eastside, mental health was a factor in 42% of all incidents involving police. The police department says its officers often have to act as first responders for mental health issues. This is because there is not enough other support for these people.

A 2013 study of SRO tenants in the wider DTES found that 74.4% had a mental illness. This included 47.4% with psychosis. Only one third of those with psychosis were getting treatment. A 2016 study of 323 people who often had contact with the law in the DTES found that 99% had at least one mental health condition.

Poverty and Income

The wider DTES area is much poorer than the rest of Vancouver. The average income there was $13,691. For the city as a whole, it was $47,229. 53% of the wider DTES population has low income. This is compared to 13.6% of people in Metro Vancouver.

In the V6A postal area, similar to the wider DTES, 6,339 residents received some form of social assistance in 2013. Of these, 3,193 were considered disabled. The basic welfare rate for single adults who can work is $610 per month. This includes $375 for shelter and $235 for all other costs ($335 since July 2017). People who support low-income DTES residents say this amount is not enough to live on. This amount has not increased since 2007. In 1981, the basic welfare rate was worth $970 per month after adjusting for inflation.

A 2008 survey of SRO residents found that their average income from all sources was $1,109 per month.

Besides mental health issues, DTES residents often find it hard to get jobs. This is due to physical disabilities, and lack of education or skills. A 2009 survey of 30 blocks in and around the DTES showed that 62% of residents over 15 were not working or looking for work. This is compared to 33% in Vancouver as a whole.

The DTES is sometimes called "Canada's poorest postal code," but this is not actually true.

Housing Challenges

Both homelessness and poor housing are big problems in the DTES. These issues make the neighbourhood's mental health challenges even worse. In 2012, there were 846 homeless people in the wider DTES area. This included 171 people who were not in any shelter. Homeless people in the DTES made up about half of the city's total homeless population. Over a third of them are Indigenous.

Thousands of DTES residents live in SROs. These provide low-cost rooms without private kitchens or bathrooms. Conditions in SROs can vary a lot. But many are known for being dirty and chaotic. Many are over 100 years old and are in very bad shape. They often lack basic things like heat and working plumbing. In 2007, it was reported that four out of five rooms had bed bugs, cockroaches, and fire safety problems. Even at their best, SROs have little living space. This means tenants spend more time in the public areas of the DTES.

SRO landlords have often been criticized for not fixing problems and for illegally evicting tenants. The city has often been slow to make SRO owners do major repairs. They say owners could not afford repairs without raising rents.

Law Enforcement and Community Relations

The VPD uses a practice called "carding" or "street checks." This is when police stop and question people they think might be involved in suspicious activity. In Vancouver, 15% of street checks are on Indigenous people. They make up only 2% of the general population. 5% of checks are on Black people, who are less than 1% of the population. Some civil rights groups believe these practices are unfair and lead to too much harassment against Indigenous and Black residents.

In 2008, the VPD started to crack down on small offences. These included selling things illegally on sidewalks and jaywalking. This ticketing stopped after community groups objected. They worried that residents with unpaid tickets would be afraid to report serious safety concerns to the police.

In 2010, police started an effort to stop violence against DTES women. This led to several violent offenders being found guilty. However, trust in the police remains low for some. Some DTES activists say that "gentrification/condos and police brutality" are the two worst problems in the neighbourhood.

In 2020, the Defund604 network was formed. They called for reducing the budget of the Vancouver Police Department. Among other requests, they asked for a $152 million budget cut to the VPD. This matched the City of Vancouver's budget shortfall due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Defund604 network is still active as of summer 2021.

Housing Availability and Cost

The City calls the housing and homelessness situation in the DTES a "crisis." Governments, experts, and community groups widely support a Housing First model. This model puts stable, good housing first. It sees housing as a necessary step before other help for homeless people or those with mental health issues. Many people with mental health needs require supportive housing.

The DTES has many low-income adults who live alone and are at risk of homelessness. So, changes in housing options for low-income adults are very important to the neighbourhood. SROs have known problems. But if an SRO resident loses their room and becomes homeless, it costs the provincial government about $30,000 to $40,000 more per year in extra services.

Changes in Housing Units and Rents

In recent years, the number of homes for low-income single people has slightly increased. In the downtown area (Burrard Street to Clark Drive), there were 11,371 units in 1993. By 2013, there were 12,126 units. The number of privately owned SROs went down by 3,283 units during this time. But the number of social housing units went up by 4,038 units. In 2014, another 300 privately owned SRO units were lost.

However, rents in many of those units have gone up. Rents in social housing units for low-income single people are set at the amount given for shelter in welfare rates. But rents in privately owned SROs can change. In 2013, 24% of privately owned SROs rented at the basic welfare shelter rate of $375 per month. This was down from 60% in 2007.

According to one group that helps tenants, the average lowest rent in privately owned hotels in the wider DTES area was $517 per month in 2015. There were no empty rooms renting for less than $425 per month.

The city has a rule to discourage turning SROs into other types of buildings. But groups that help SRO tenants say the city's rule does not go far enough. It does not stop rent increases. The city says that only the province, not the city, has the power to control rents. They say the province should raise welfare rates.

Since 2007, the provincial government has bought 23 privately owned SRO hotels in the wider DTES area. These have 1,500 units. They did major renovations in 13 of those buildings. This cost $143.3 million, with $29.1 million paid by the federal government. Because of rising rents and often very bad conditions in the remaining 4,484 privately owned SROs, DTES activists have called for governments to replace them. They want another 5,000 social housing units for low-income single people.

Migration to the DTES

The DTES has a history of attracting people with mental health issues from all over B.C. and Canada. Many are drawn by its affordable housing and services. Between 1991 and 2007, the DTES population grew by 140%.

A 2016 study found that 52% of DTES residents who experience long-term homelessness and serious mental health issues had moved from outside Vancouver in the past 10 years. This number has tripled in the last decade. The same study found that once people moved to the DTES, their conditions often got worse.

A 2013 study of tenants in DTES SROs found that 93% of those surveyed were born in Canada. But only 13% were born in Vancouver. Vancouver Coastal Health estimates that half of the people who use its health services in the DTES are long-term residents. They also estimate that 15 to 20% of the population changes each year.

|

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |