Edmund Curll facts for kids

Edmund Curll (born around 1675 – died 11 December 1747) was a well-known English bookseller and publisher. He became famous, especially because of the writer Alexander Pope, for publishing books in ways that some people thought were unfair or sneaky. Curll started with very little money but became rich by being clever and sometimes tricky in his publishing business. He made money from popular news stories, sold special medicines, and used any kind of attention to help his business grow. He published all sorts of books, whether they were high quality or not, as long as they sold well. He was born in the West Country, and his father was a tradesman. He began his career in 1698 as an apprentice to a London bookseller.

Contents

How He Started Publishing

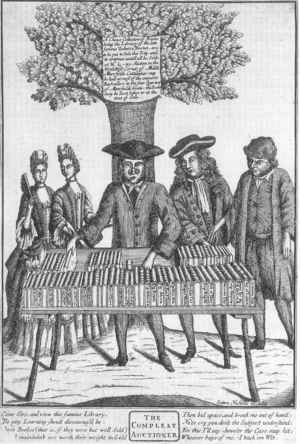

After finishing his seven-year training, Edmund Curll began selling books at auctions. His old boss, Richard Smith, went out of business in 1708, and Curll took over his shop. Early on, Curll often worked with other booksellers. They would write, publish, and sell pamphlets and books. He was good at using any big news story to create "accounts" and arguments.

For example, in 1712, a witch trial involving Jane Wenham was very popular. Curll worked with partners: one wrote a pamphlet saying she was innocent, while another wrote one saying she was guilty. Both pamphlets were sold in all three shops. He even created fake arguments between the "authors" in newspapers to get free advertising.

His Unique Book Shop

Curll's book collection was always very mixed. As a publisher, he made inexpensive books on cheap paper. Most of his books cost only one or two shillings, which meant regular people like tradesmen, apprentices, and servants could afford them. He also published political writings for the Whig group.

Some of his early books included serious titles like John Dunton's The Athenian Spy. But he also sold more playful books like The Way of a Man with a Maid. Curll also sold actual medical cures and was very bold in promoting them. In 1708, he published The Charitable Surgeon, which pretended to be a medical advice book. It claimed that a cure by John Spinke was useless and that the only good cure came from Curll's own shop. Dr. Spinke wrote a pamphlet to answer this, and Curll, in his usual style, wrote a reply. To create more buzz, Curll made a wild claim that Spinke was uneducated and offered five pounds if Spinke could translate five lines of Latin at Curll's shop. Spinke did it and used the money to buy some of Curll's "cure," which he had tested. It turned out Curll's "cure" was also just mercury! But Curll kept publishing his Charitable Surgeon, adding "a new method of curing."

By 1712, Curll's shop was so successful that he opened another one in Tunbridge Wells. He also moved to a bigger store on Fleet Street in London. Around this time, he started writing some of his own pamphlets. In 1712, he worked with John Morphew, a Tory publisher, to make money from the excitement around the Henry Sacheverell controversy. After this, Curll was able to hire one of Morphew's writers.

Publishing Without Permission

One big part of Curll's career, which made his reputation last, was publishing works that originally came from another publisher, often without the author's permission. Usually, Curll managed to stay just within the law, but not always.

In 1707, Curll announced in newspapers that he would publish Poems on Several Occasions by Matthew Prior. However, Jacob Tonson had the only rights to Prior's works. Curll published them anyway. In 1716, Curll again announced he would publish Prior's works, and Prior himself wrote letters of protest to the newspapers. But the arguments with Tonson and Prior's objections only served as free advertising, and Curll published the book anyway.

The Swift and Pope Problems

In 1710, Curll printed Jonathan Swift's Meditation Upon a Broomstick. That same year, he wrote a "key" to other Swift works, and in 1713, he made a key to A Tale of a Tub. Swift was annoyed that Curll revealed he was the author (as Swift was rising in the Church of England). However, Swift also found it funny how dull Curll's explanations of his works were. He wrote to Alexander Pope that publishers like Curll were useful for writers who wrote satire. Curll kept publishing Swift's works, especially after Swift used Curll's notes (without permission) in his own A Tale of a Tub. In 1726, Curll produced a very wrong "key" to Swift's Gulliver's Travels.

Another case of publishing without permission involved the poet Edward Young. Young sent a poem to Curll for publishing, along with a letter. When the poem was published in 1717, Young placed an advertisement claiming the poem and letter were fake. In reality, the poem praised a politician who had lost his job, and Young's letter was real.

Curll's connection with the anonymously published Court Poems in 1716 led to a long fight with Alexander Pope. Curll got three poems that were anonymous, but written by Pope, John Gay, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Pope wrote to Curll warning him not to publish the poems, which only made Curll sure of who wrote them. So, he published them.

In response, Pope and his publisher, Bernard Lintot, met with Curll at a tavern. Pope and Lintot seemed to give up, only worrying about John Gay. However, they had put something in Curll's drink that made him very sick when he went home. Pope then published two pamphlets about the event and told the public that Curll was dead. Curll used this attention for his own benefit. He published and advertised The Catholick Poet by John Oldmixon and The True Character of Mr Pope and his Writings by John Dennis. He reprinted these in 1716, when England was in a tense mood after the failure of the Jacobite rising of 1715.

The next part of the Pope/Curll battle happened in 1716. Curll got a version of the first Psalm that Pope had written years earlier. He published it and announced he would be the future publisher of all Pope's works. Also that year, Curll was sent to jail for publishing details of the trial of the Earl of Winton. As soon as he was out, he produced a biography of Dr. Robert South, a former head of Westminster School. He had also printed the praise for Dr. South written by the current school head. He was invited to the school and expected to be honored for his work. Instead, the students made him kneel and beg for an apology. Then they wrapped him in a blanket and tossed him in the air, hitting him with sticks. Samuel Wesley, a student there and older brother to John Wesley, wrote a funny poem about the blanket incident. Curll thought Pope and his friends were behind this. He then started using a "phantom poet." He published a poem called "The Petticoat" by "J. Gay." This poet was Francis Chute, who used the fake name "Joseph Gay." Curll used this trick two more times to take sales away from John Gay's poems and to annoy Pope and his friends.

Quick Biographies and "Curlicisms"

Curll was known for quickly getting biographies written about famous people as soon as they died. He would publish them without caring if they were accurate or made-up. John Arbuthnot once joked that Curll's biographies had become "one of the new terrors of death." This meant people were scared of dying because Curll would publish a quick, possibly untrue, story about them.

Curll's main goal was to be the first to sell a biography, not to make it the best or most accurate. So, he would announce a biography was coming and ask the public to send in any memories, letters, or speeches of the person who died. He would then include these (and sometimes nothing else) in the "biography." He didn't care about accuracy and would take stories from enemies as easily as from friends. If he didn't get enough contributions, he would hire a writer to invent things. In 1717 alone, he published biographies of Bishop Burnet and Elias Ashmole. He later published a quick biography of Swift, just as Swift had predicted. There was almost no way to stop Curll's press. In 1721, he published a biography of the Duke of Buckingham. He was called before the House of Lords for a trial, and the Lords made a new law making it illegal to publish anything about a lord without permission.

Curll became so well-known for his publications that the word "Curlicism" became a term for writings that were considered improper. In 1718, Curll published Eunuchism Display'd, and Daniel Defoe criticized it, calling it a "Curlicism." Curll used this criticism to his advantage by writing Curlicism Display'd as a defense. However, this pamphlet was actually just a list of books in Curll's shop, so he turned the whole thing into an advertisement.

In 1724, he published Venus in the Cloister, a translation of an old French book. That year, an anonymous complaint to the Lords mentioned this as improper writing. As with past issues, Curll tried to make money from it by publishing The Humble Representation of Edmund Curll and quickly releasing a new edition of Venus in the Cloister. He was arrested in March and held until July. The courts found there was no specific law against obscenity, so they charged him for publishing something that wasn't allowed. Curll published an apology and promised to stop publishing, but the apology was also an advertisement for two new books.

While Curll was in prison, he met John Ker, who wanted his life story published. This work contained government secrets from the time of Queen Anne, so Curll was worried. He wrote to Robert Walpole for permission. Getting no answer, he took the silence as a "yes" and published the book. The last part of the memoirs was done by Edmund's son, Henry Curll. Both Henry and Edmund were arrested. They spent fourteen months in prison (until February 1728), were fined, and sentenced to an hour in the pillory (a public punishment) for publishing Ker's memoirs. Curll wrote and published a paper for his pillory day, saying he published Ker's memoirs only out of loyalty to the old queen. Because of this, the crowd did not harm him. Instead, they cheered Curll and carried him away on their shoulders.

The Dunciad Battle

Pope and Curll had another fight in 1726 when Curll published some of Pope's letters without permission. Pope got his revenge by making Curll a very important and ridiculed character in his 1728 poem, Dunciad. In fact, no one, not even the "King of Dunces" Lewis Theobald, was made fun of as much as Edmund Curll in Dunciad.

Curll's response was to print a copied edition of the poem. Then he made a "Key" to the poem to explain all the people Pope attacked. After that, he published poems that attacked Pope personally. The Popiad, possibly written by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, The Female Dunciad, and The Twickenham Hotch-Potch all came out in 1728 as answers to Pope. In 1729, Pope's Dunciad Variorum continued to criticize Curll in prose. Curll then produced The Curliad: a Hypercritic upon the Dunciad Variorum. This book included his autobiography, a defense against claims of improper publishing, and a defense of his actions with Pope.

Later in 1729, Curll planned to publish a book by William Congreve. John Arbuthnot complained in the newspapers about Curll's plan. So, Curll renamed his shop "Congreve's Head" and put up a statue of Congreve to annoy Arbuthnot and Congreve's friends. In 1731, he moved his shop to Burleigh Street and advertised an upcoming life story of Pope, saying, "Nothing shall be wanting but his (universally desired) Death."

In response to his request for materials, someone known as "P.T." offered Curll some of Pope's letters. However, the letters were fake, and the whole offer had been a trap set by Pope. Pope then published a correct version of his letters in 1735. Curll moved his shop again that year and called it "Pope's Head," selling under Pope's sign. Two years later, he published five volumes of Pope's letters. In 1741, Pope finally won against Curll in court. A court ruled that letters belong to the author, even if someone else receives them.

Later Years

In his final years, Curll continued to publish his unique "Curlicisms" mixed with more serious and valuable works. His will shows that his son had died without children and that only his wife was left in his family. Edmund Curll passed away in London on 11 December 1747.

See also

In Spanish: Edmund Curll para niños

In Spanish: Edmund Curll para niños

- Elizabeth Barry (an actress whose biography Curll published)

- Charles Gildon (another biographer whose accounts are still used today)

- Elizabeth Thomas, who became famous in Pope's Dunciad as "Curll's Corinna" because of her connection with Curll.

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |