Tar River spinymussel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tar River spinymussel |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

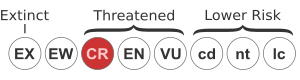

The Tar River spinymussel (Parvaspina steinstansana) is a special type of freshwater mussel. It belongs to the Unionidae family, also known as river mussels. This unique mussel is only found in North Carolina in the United States. Without help from people, it is expected to disappear forever. Because of this, it is listed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Contents

What is the Tar River Spinymussel?

Tar River spinymussels are yellowish-brown when they are young. As they get older, their shells turn a darker brown. These mussels get their name from the small spines on the back edge of their shells. Each shell can have up to six spines. The largest Tar River spinymussels grow to be about 5.5 centimeters (2.2 inches) long.

Where Do Tar River Spinymussels Live?

This mussel species lives only in North Carolina. When a plan was made to help them, the main groups of Tar River spinymussels were found in the Tar River and Swift Creek. The Tar River had two small groups, and Swift Creek had one larger group. All these groups were able to have babies. It is thought that there are only about 100 to 500 Tar River spinymussels left.

Historically, these mussels lived only in the Tar and Neuse rivers. Before people settled in this area in the 1700s, they likely lived in many large waterways there. Some groups in Shocco Creek, the Tar River, and the Neuse River might have already disappeared. Smaller groups still exist in Sandy Creek, Fishing Creek, and Little River. However, these groups are very separated from each other.

The Tar River spinymussel lives in a very small area. This means there are not many places suitable for them to live. In the Tar River basin, they live in small, scattered groups. In the Neuse River basin, even fewer are found. These mussels prefer loose beds of coarse sand and gravel. They are often found in wooded areas near streams. They need fast-flowing, clean water with less dirt and pollution.

How Many Spinymussels Are Left?

From 2014 to 2020, scientists looked for these mussels. They found only 11 mussels despite searching very hard. This shows that the number of mussels is still going down. There are currently fewer than five groups of Tar River spinymussels. These groups have few mussels and are not connected. Even though few have been found, it is possible that thousands more are still living. We do not know how many mussels there were in the past. However, their old living areas could have supported many more.

Life and Habits of the Spinymussel

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Female spinymussels carry their babies from early April to mid-July. At the end of this time, they release special packets called conglutinates into the water. These packets contain tiny baby mussels called glochidia. The females release these packets many times during one season. This means they can have babies more than once.

The baby glochidia need certain fish to grow. The white shiner, the pinewoods shiner, and the bluehead chub are fish that act as hosts. The glochidia attach to these fish to develop. Warmer water temperatures make the glochidia detach from their hosts faster. Tar River spinymussels grow about 0.7 to 1.4 millimeters each year. A similar endangered mussel, the James River spinymussel, has a similar life cycle. Studies show that female James River spinymussels can release between 90 and 168 conglutinates. Young Tar River spinymussels are about 4 to 10 millimeters (0.16 to 0.39 inches) long.

What Do Spinymussels Eat?

Like many other mussels, Tar River spinymussels are filter feeders. They pull water into their bodies and filter out tiny bits of food. They eat algae, plankton, and small dirt particles called silt. This way of eating helps to clean the water around them.

How Spinymussels Behave

The Tar River spinymussel creates conglutinates, which are full of their baby larvae, the glochidia. These conglutinates are made to attract their host fish. Many types of minnows try to eat these packets. This makes minnows a known host species for the Tar River spinymussel glochidia. The glochidia then attach to the host fish. Once they have grown enough, they will detach. When this mussel reproduces, females can release up to four or five times the amount of conglutinates.

Dangers to the Spinymussel

Too Much Sediment: When too much dirt and sand, called sediment, enters streams and rivers, it harms the water quality. This is bad for the Tar River spinymussel's home. Lots of floating sediment can clog the mussels' gills. It also changes the sand and gravel on the riverbed. Less light can get through the water, which means less food for the mussels.

Runoff Water: A lot of water running off paved areas can damage the riverbanks where these mussels live. Water running off from farms, homes, and construction sites carries harmful chemicals. These chemicals are a big danger to the mussels. For example, Pesticides caused many mussels to die in the Tar River in 1990.

Logging Operations: When trees are cut down in the Tar and Neuse river basins, wood and debris can fall into the water. This makes the mussels' home worse. Removing large trees that hold the riverbanks in place also harms their habitat.

Poor Wastewater Management: Places that treat wastewater along the Tar River have sometimes broken rules about pollution. Wastewater can put toxic chemicals, diseases, and tiny plastic pieces called microplastics into the mussels' habitat.

Protecting the Spinymussel

The Tar River spinymussel was listed as endangered on June 27, 1985. A full report on its current status is not yet ready.

A five-year review for the Tar River spinymussel started on June 20, 2019. This review helps decide if the mussel should still be protected. It looks at its history, where it lives, and what threatens it.

To decide if the mussel is still endangered, scientists looked at dangers like habitat changes, overuse, disease, and climate change. When they tracked the mussels, only eleven wild ones were found. These very low numbers show that the species is still declining. Because of the low numbers and ongoing threats, the Tar River spinymussel still needs protection. The review concluded that it should remain an endangered species.

The five-year review also talks about a plan to help the mussels recover. It suggests bringing mussels back into the wild. It also recommends reducing threats and restoring their habitat.

Recovery Plan for the Spinymussel

The recovery plan was first made in 1985, updated in 1992, and changed again in 2019. In 1985, the reasons for listing the mussel as endangered included habitat damage, overuse, disease, lack of rules, and new species being introduced. The 1985 plan said there was no need to mark special "critical habitat" areas, and this has not been updated.

To move the Tar River spinymussel from endangered to threatened, the 1992 plan had four goals:

- All groups of mussels must show they can reproduce.

- At least two new groups must be found.

- All groups and their homes must be safe from future threats.

- All group sizes must stay the same or grow for 15 to 20 years.

In 2019, these goals were changed in three ways:

- At least seven smaller groups must grow or stay stable.

- These seven groups must include one in the Tar River basin and one in the Neuse River basin.

- Threats must be managed so the species can survive far into the future.

Some actions to meet these goals include using existing laws, getting support through education, and finding and watching mussel groups.