Emil du Bois-Reymond facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

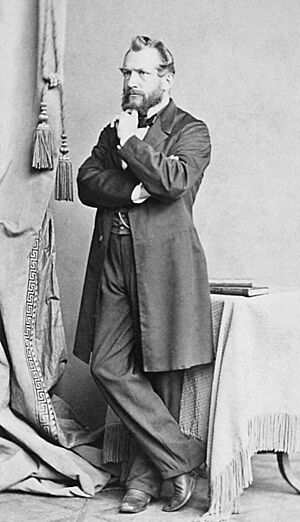

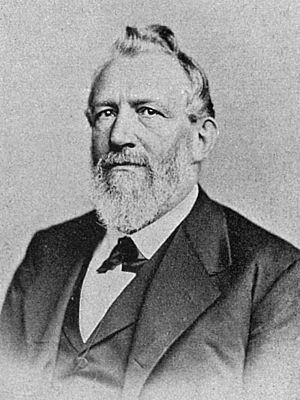

Emil du Bois-Reymond

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 7 November 1818 |

| Died | 26 December 1896 (aged 78) Berlin, Germany

|

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

| Known for | Nerve action potential |

| Spouse(s) | Jeannette du Bois-Reymond, née Claude |

| Children | 9 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Doctoral advisor | Johannes Müller |

| Other academic advisors | Karl Bogislaus Reichert, Heinrich Wilhelm Dove, Gustav Magnus |

| Notable students | William James |

| Influences | Lucretius, Comte |

| Influenced | Eduard Hitzig, Julius Bernstein |

Emil Heinrich du Bois-Reymond (born November 7, 1818 – died December 26, 1896) was an important German doctor and scientist. He helped discover how nerves send electrical signals, called action potentials. He also developed a new way to study electricity in living things, known as experimental electrophysiology.

Contents

Life of a Scientist

Emil du Bois-Reymond was born in Berlin, Germany, and lived there his whole life. His younger brother, Paul, became a mathematician. Emil's father was an immigrant from Switzerland, and his mother came from a well-known French family living in Berlin.

Early Education and Studies

Emil first went to the French College in Berlin. In 1838, he started studying at the University of Berlin. At first, he wasn't sure what to study. He explored history, geology, and physics. But he soon found his passion in medicine.

His dedication caught the eye of Johannes Peter Müller, a famous professor. Müller taught both anatomy (the study of body structure) and physiology (the study of how the body works).

Discovering Animal Electricity

In 1840, Professor Müller made Emil his assistant. Müller gave Emil a paper about electricity in animals, written by an Italian scientist named Carlo Matteucci. This paper changed Emil's life.

Emil decided to study Electric fishes for his final project. This was the start of his long research into bioelectricity, which is electricity produced by living things. He published his findings in a major work called Investigations of Animal Electricity. The first part came out in 1848, and the last part in 1884.

In 1853, Emil married Jeannette Claude, a distant cousin he met in England. He was known to be an agnostic or atheist, meaning he didn't follow a specific religion.

His Scientific Work

Emil du Bois-Reymond's book, Investigations of Animal Electricity, was very important. It carefully described and analyzed the electrical events in living creatures. This book greatly advanced our understanding of biology.

He created new ways to study these electrical signals. He also invented or improved tools for observation.

Understanding Bioelectricity

Du Bois-Reymond proposed a theory about bioelectricity. He thought that living tissues, like muscles, were made of tiny "electric molecules." He believed that the muscle's electrical behavior came from these tiny units.

Today, we know these "electric molecules" are actually tiny charged particles called ions, like sodium and potassium. The way these ions move in and out of cells creates electrical signals.

Challenges and New Discoveries

Other scientists, like Ludimar Hermann, questioned Emil's theory. Hermann believed that healthy living tissue only made electric currents if it was injured.

This debate was settled in 1902 by Emil's student, Julius Bernstein. Bernstein combined parts of both theories. He created a model that explained how ions create the action potential (the electrical signal) in nerves and muscles.

Emil du Bois-Reymond focused mostly on animal electricity. But he also studied other things using physical methods. These included how substances spread (diffusion), how muscles produce lactic acid, and how electric fish create shocks.

A Great Teacher and Leader

In 1858, Emil became a professor of physiology at the University of Berlin. He held this position until he died. For many years, he did his research without a proper lab. But in 1877, the government gave the university a modern physiology laboratory, which was his dream.

He became a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin in 1851. In 1876, he became its permanent secretary. Like his friend Hermann von Helmholtz, Emil was very famous in Germany. He used his influence to help science grow. He introduced new ideas like thermodynamics (the study of heat and energy) and Darwin's theory of evolution to his students. He was also known for his speeches on literature, history, and philosophy.

His Speeches and Ideas

Emil du Bois-Reymond was a talented speaker. He gave many talks on different topics.

On Nationalism

During the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Emil made a strong statement. He said the University of Berlin was like the "intellectual bodyguard" of the German royal family. But after the war ended, he regretted his words. He felt sad about the "national hatred" between the two countries.

In 1878, he gave a lecture called "On National Feeling." In this talk, he explored the idea of nationalism. It was one of the first deep analyses of this topic.

On Darwinism

Emil du Bois-Reymond was the first German professor to support Darwinism. He taught about Darwin's theory in his classes at the University of Berlin. He also gave talks about it in other cities. His ideas were translated and shared across Europe and North America.

Unlike some others, Emil saw natural selection as a mechanical process, which is closer to how scientists understand it today. Most people in Germany didn't mind his teachings until 1883. That year, his obituary for Darwin upset some conservative and Catholic groups.

On Big Questions (Epistemology)

In 1880, Emil gave a famous speech to the Berlin Academy of Sciences. He listed seven "world riddles" or "shortcomings" of science. These were big questions that science might not be able to answer.

Here are some of them:

- The basic nature of matter and force.

- How motion began.

- How life began.

- Why nature seems to have a purpose (like how eyes are perfectly designed for seeing). He thought this wasn't a completely unanswerable question.

- How we get simple feelings or sensations (he called this a "quite transcendent" question, meaning beyond our understanding).

- How intelligent thought and language began.

- The question of free will.

For the first, second, and fifth questions, he famously said, "Ignorabimus" (meaning "we will never know"). For the question of free will, he said, "Dubitemus" (meaning "we doubt it").

See also

In Spanish: Emil du Bois-Reymond para niños

In Spanish: Emil du Bois-Reymond para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |