Ernst Niekisch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernst Niekisch

|

|

|---|---|

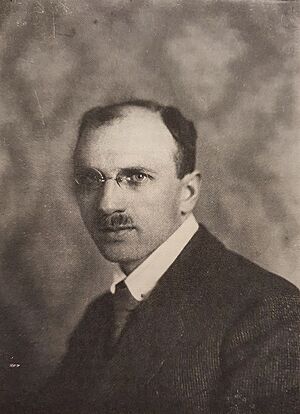

Portrait of Ernst Niekisch in 1926

|

|

| Born |

Ernst Niekisch

23 May 1889 Trebnitz, Province of Silesia, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire

|

| Died | 23 May 1967 (aged 78) West Berlin, West Germany

|

| Era | 20th century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Conservative Revolution |

|

Main interests

|

Politics |

Ernst Niekisch (born May 23, 1889 – died May 23, 1967) was a German writer and politician. He started his political journey with the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Later, he became a key figure in a group called the National revolutionary branch of the Conservative Revolution and National Bolshevism.

Contents

Early Life and Politics

Ernst Niekisch was born in Trebnitz, a town in Silesia. He grew up in Nördlingen. After studying to become a teacher, he served one year in the military. He then became a public school teacher in Augsburg. From 1914 to 1917, he served in the Imperial German Army during WWI.

In 1917, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany. He returned to Augsburg as a teacher. He played a big part in setting up the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919. For a short time, Niekisch was very powerful as the head of the Bavarian councils. He left the SPD soon after but later rejoined it. In 1925, he spent a short time in prison for his role in a failed attempt to change the government in Bavaria.

Nationalist Ideas

In the 1920s, Niekisch strongly believed in nationalism. This means having a strong sense of pride and loyalty to one's own country. He tried to make the Social Democratic Party focus more on national pride. He strongly disagreed with agreements like the Dawes Plan and the Locarno Treaties. He also disliked the general idea of pacifism (being against war) that the SPD supported. Because of these disagreements, he was removed from the party in 1926.

After leaving the SPD, Niekisch joined the Old Social Democratic Party of Saxony. He influenced this party with his own ideas of socialism mixed with nationalism. He started his own magazine called Widerstand (Resistance). He and his followers called themselves "National Bolsheviks." They saw the Soviet Union as a continuation of both Russian nationalism and the old state of Prussia. Their slogan was "Sparta-Potsdam-Moscow." This meant combining ancient Greek strength (Sparta), Prussian military tradition (Potsdam), and Soviet power (Moscow).

Niekisch was also part of a group called ARPLAN. This group studied the Russian Planned Economy. Through this group, he visited the Soviet Union in 1932. He liked Ernst Jünger's book Der Arbeiter, which he saw as a plan for a National Bolshevik Germany. He also believed that Germany and the Soviet Union should become allies. He thought this alliance would stand against the "decadent West" and the Treaty of Versailles. The idea of combining extreme nationalism and communism was unusual. This meant Niekisch's National Bolsheviks did not have much support.

During the Third Reich

Niekisch did not like Adolf Hitler. He felt that Hitler did not truly believe in socialism. Instead, Niekisch looked to Joseph Stalin and the industrial growth of the Soviet Union as his ideal leader. In 1958, Niekisch wrote that Hitler was a leader who only cared about power. He saw Hitler as an enemy of the idea of an elite, special group of leaders that Niekisch supported.

Niekisch particularly disliked Joseph Goebbels, a top Nazi official. At one meeting, Niekisch and Goebbels almost got into a fight. In 1932, Niekisch wrote a pamphlet called Hitler – ein deutsches Verhängnis (Hitler – a German Disaster). This pamphlet openly criticized Nazism. After the Reichstag fire, Niekisch's house was searched by the police. They were looking for any involvement, but nothing came of it. He also talked about his opposition to the new government with Ulrich von Hassell. However, Niekisch did not join the German Resistance.

Despite his criticisms, Niekisch was allowed to continue editing Widerstand until it was banned in December 1934. In 1935, he visited Rome and met with Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy. Mussolini told Niekisch that he thought Hitler's aggressive plans against the Soviet Union were foolish.

In 1937, the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, arrested Niekisch and many of his friends. They were arrested for writing articles against the Nazi government. In 1939, Niekisch was found guilty of "literary high treason" by the Volksgerichtshof, a special Nazi court. He was sentenced to life in prison. His family was able to keep his property, but they could not get him released. Niekisch stayed in prison until April 1945, when the Red Army freed him. By then, he had almost lost his eyesight.

Later Life

After his time in prison, Niekisch was very bitter about nationalism. He changed his views and became a supporter of Marxism. He taught sociology at Humboldt University in East Germany. In 1953, he became disappointed by the harsh way the workers' uprising was stopped. Because of this, he moved to West Berlin, where he passed away in 1967.

Legacy

After his death, Ernst Niekisch became one of several writers whose ideas were promoted by groups like the Groupement de recherche et d'études pour la civilisation européenne. These groups were interested in the Conservative Revolutionary movement.

Works

- Der Weg der deutschen Arbeiterschaft zum Staat. Verlag der Neuen Gesellschaft, Berlin 1925.

- Grundfragen deutscher Außenpolitik. Verlag der Neuen Gesellschaft, Berlin 1925.

- Gedanken über deutsche Politik. Widerstands-Verlag, Dresden 1929.

- Politik und Idee. Widerstands-Verlag Anna Niekisch, Dresden 1929.

- Entscheidung. Widerstands-Verlag, Berlin 1930.

- Der politische Raum deutschen Widerstandes. Widerstands-Verlag, Berlin 1931.

- Hitler – ein deutsches Verhängnis. Drawings by A. Paul Weber. Widerstands-Verlag, Berlin 1932.

- Im Dickicht der Pakte. Widerstands-Verlag, Berlin 1935.

- Die dritte imperiale Figur. Widerstands-Verlag 1935.

- Deutsche Daseinsverfehlung. Aufbau-Verlag Berlin 1946, 3. Edition Fölbach Verlag, Koblenz 1990, ISBN: 3-923532-05-9.

- Europäische Bilanz. Rütten & Loening, Potsdam 1951.

- Das Reich der niederen Dämonen. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1953.

- Gewagtes Leben. Begegnungen und Begebnisse. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Köln und Berlin 1958.

- Die Freunde und der Freund. Joseph E. Drexel zum 70. Geburtstag, 6. Juni 1966., Verlag Nürnberger Presse, Nürnberg 1966.

- Erinnerungen eines deutschen Revolutionärs. Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Köln.

See also

- Karl Otto Paetel