Fortifications of London facts for kids

London has had many defenses over time. While some old walls and forts were taken down in the 1600s and 1700s, many others still stand. Famous examples include the amazing Tower of London, which is now a popular place to visit.

Contents

History of London's Defenses

Roman Times: The First Walls

London's very first defensive wall was built by the Romans around 200 AD. This was about 80 years after they built a fort in the city. The fort's north and west walls were made thicker and taller to become part of the new city wall. London itself, then called Londinium, was founded about 150 years before the wall was built.

The London Wall was used for over 1,000 years! It helped protect London from attacking Saxons in 457 AD and was still important in the Middle Ages.

The wall had six main entrances, or gates, that the Romans built at different times. These gates, going clockwise from west to east, were: Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Bishopsgate, and Aldgate. Later, in the Middle Ages, a seventh gate called Moorgate was added between Cripplegate and Bishopsgate.

Middle Ages: Castles and Stronger Walls

After the Normans took over England in 1066, they added more defenses to London. These new forts helped protect the Normans from the people of London, as well as from outside attackers.

King William built two important forts:

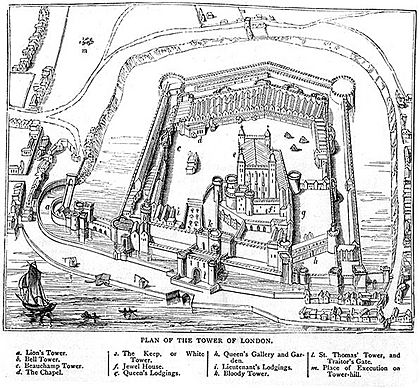

- The White Tower, which was the first part of the Tower of London, was built in 1078. It stood to the east of the city, near the River Thames.

- Baynard's Castle was built to the southwest of the Tower, close to the River Fleet.

A third fort, Montfichet's Castle, was built to the northwest by Gilbert de Monfichet, who was related to King William.

Later in the medieval period, the city walls were made even stronger. They added crenellations (notches for defense) and more gates and towers.

City Gates: Checkpoints and Prisons

The large buildings that once guarded the entrances through the City Wall were called city gates. They had big archways for people and carts to pass through. These gates were protected by heavy doors and portcullises (strong metal grates that could be lowered). They were sometimes used as prisons.

When the curfew bells rang at nine o'clock (or dusk), the gates would close. They would open again at sunrise or six o'clock the next morning. No one was allowed to enter or leave during these hours, and people inside were supposed to stay home. The gates also served as checkpoints to control who entered the city and to collect tolls. These tolls helped pay for keeping the wall in good repair.

The gates were fixed and rebuilt many times over the years. After the king returned to power in 1660, the gates were left open and their portcullises were lifted. This meant they could no longer defend the city, but they remained as a symbol of London's importance. Most of the gates were taken down around 1760 because they caused too much traffic.

Today, most of the old gate locations are marked by main roads with the same names. Only Cripplegate is a small street, a bit north of where the actual gate used to be.

London Bridge: A Fortified Crossing

"Old London Bridge was also built to defend against attacks. The end of the bridge in Southwark was protected by the Great Stone Gate. This gate was likely finished around 1209. In 1437, this gatehouse fell into the Thames but was rebuilt between 1465 and 1466.

There was a second line of defense: a drawbridge. This drawbridge could be raised to stop attackers coming from the south. It also let merchant ships pass upstream to the docks. When lowered, it could stop enemy ships from attacking from the other side. The drawbridge was supported by a stone gatehouse built between 1426 and 1428. This was known as the Drawbridge Gate. The Drawbridge Gate was taken down in 1577. The Great Stone Gate was rebuilt in 1727 but no longer had a military purpose. It was completely removed in 1760.

17th Century: Civil War Defenses

During the English Civil War, between 1642 and 1643, special defenses called the Lines of Communication were built around London. These were ordered by Parliament to protect the city from attacks by King Charles I's armies. By 1647, the danger was over, and Parliament had these defenses taken down.

19th Century: Invasion Plans

The London Defence Positions were a plan made in the 1880s to protect London if a foreign army invaded from the south coast. This plan involved a line of trenches that could be dug quickly if there was an emergency. Along this line, there were thirteen small, permanent forts called London Mobilisation Centres. These centers held all the supplies and ammunition needed for the soldiers who would dig and defend the trenches.

These centers were built along a 70-mile stretch from Guildford to the Darenth valley, and one across the Thames at North Weald in Essex. However, they were soon seen as old-fashioned. All but one were sold off by 1907. Fort Halstead is now used by the Ministry of Defence for explosives research.

World War I and II: Modern Threats

During World War I, parts of the London Defence Positions plan were used again to create a defensive line in case of a German invasion. This line was extended north to the River Lea and south to Halling, Kent, connecting to the defenses around Chatham.

More defenses were prepared for London during World War II when there was a threat of invasion in 1940. This included building shelters and strong points against air attacks in the city. They also prepared defense positions outside the city against land attacks. The GHQ Line was a very long and important anti-tank defense line. It was built to protect London and England's industrial areas. It ran from the Bristol area, much of it along the Kennet and Avon canal. It then turned south near Reading and went around London, passing just south of Aldershot and Guildford. From there, it headed north through Essex.

Inside the GHQ Line, there were rings of defenses around London: the Outer (Line A), Central (Line B), and Inner (Line C) London Defence Rings.

In the city itself, the Cabinet War Rooms and the Admiralty Citadel were built to protect important command centers. A series of deep-level shelters were also prepared as safe places for people during bombing raids. In June 1940, under the direction of General Edmund Ironside, rings of anti-tank defenses and small concrete bunkers (pillboxes) were built. These included the London Inner Keep, London Stop Line Inner (Line C), London Stop Line Central (Line B), and London Stop Line Outer (Line A). However, work on these lines was stopped weeks later by General Alan Brooke, who preferred mobile warfare over fixed defenses.

After World War II, during the Cold War, more strong defenses were built in the city to protect command and control centers. Some existing strongholds were improved, and new ones were built, including PINDAR, the Kingsway telephone exchange, and possibly Q-Whitehall. Much of this work is still kept secret.

Terrorism Defenses: The "Ring of Steel"

London is a major target for terrorism. It has faced bombings by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and, more recently, by other extremist groups like the 7 July 2005 London bombings. In the late 1980s, the IRA planned attacks to disrupt the City of London. Two large truck bombs exploded in the City of London: the Baltic Exchange bomb in April 1992, and the Bishopsgate bombing a year later.

In response, the Corporation of the City of London changed how roads entered the city. They added checkpoints that can be staffed when the threat level is high. These measures are known as the "ring of steel". This name came from the strong defenses that used to surround the center of Belfast.

Most of the rest of London (except for obvious targets like Whitehall, the Palace of Westminster, royal homes, airports, and some embassies) does not have such visible protection. However, London is heavily watched by CCTV cameras. Many important buildings now have concrete barriers to protect against truck bombs.

See also

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |