History of London facts for kids

London is the capital city of England and the United Kingdom. Its history goes back over 2,000 years! During this time, London has become one of the world's most important cities for money and culture. It has survived many tough times, like the Great Plague, the huge Great Fire, civil wars, bombings from the sky, and other challenges.

The City of London is the oldest part of the bigger London area. Today, it's mainly a financial hub, but it's only a small piece of the whole city.

Contents

- London's Early Beginnings: Prehistory

- London's Ancient History

- London's Modern History

- Tudor London: Growth and Change (1485–1604)

- Stuart London: Plague, Fire, and Rebuilding (1603–1714)

- 18th Century London: A Growing Empire's Heart (1700s)

- 19th Century London: A Global Powerhouse (1800s)

- 20th Century London: Wars and Modernization (1900s)

- 21st Century London: A Modern Metropolis

- London's Population Over Time

- Famous Historical Sites in London

- Images for kids

- See also

London's Early Beginnings: Prehistory

Scientists have found signs that people lived near the River Thames in the London area a very long time ago. At a place called Fulham Palace, tools made from flint stone show that people were there in the Stone Age, thousands of years ago. It seems this spot was once a small island in the river.

Later, in the Bronze Age, around 1750 BC to 1285 BC, parts of a wooden bridge were found near Vauxhall Bridge. This bridge might have crossed the Thames or led to an island that's now gone. Even older wooden structures, from about 4800 BC to 4500 BC, were found in the same area. We don't know what these very old structures were for. All these discoveries are on the south side of the river, where the River Effra meets the Thames, a natural place to cross.

Experts believe that London was mostly started by the Romans, as not many signs of large settlements from before the Romans have been found.

London's Ancient History

Roman London: A New City (47–410 AD)

The Romans built a town called Londinium around 47 AD, just a few years after they invaded Britain. They chose this spot because the River Thames was narrow enough to build a bridge, which made it easy to travel to and from Europe. Early Roman London was quite small, about the size of Hyde Park today.

Around 60 AD, a fierce queen named Boudica and her tribe, the Iceni, destroyed the city. But the Romans quickly rebuilt Londinium as a planned town. It grew fast over the next few decades. By the 2nd century, Londinium was a very important city with about 60,000 people. It had big public buildings, including a huge hall called a basilica, temples, bath houses, an amphitheatre, and a large fort for soldiers.

Between 180 AD and 225 AD, the Romans built a strong defensive London Wall around the land side of the city. This wall was about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) long, 6 meters (20 feet) high, and 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) thick. This wall lasted for 1,600 years and shaped the City of London's borders for many centuries. Even today, the edges of the City are roughly where the old wall stood.

Londinium was a diverse city. People from all over the Roman Empire lived there, including people from Britain, Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

In the late 200s AD, Saxon pirates attacked Londinium several times. Because of this, another wall was built along the river from about 255 AD. Six of London's traditional seven city gates, like Ludgate and Newgate, were originally built by the Romans.

By the 5th century, the Roman Empire was weakening. In 410 AD, the Romans left Britain. After this, Londinium quickly declined and was almost empty by the end of the 400s.

Anglo-Saxon London: A New Beginning (5th Century – 1066)

For a long time, people thought the Anglo-Saxon settlers avoided the old Roman city. But in 2008, an Anglo-Saxon cemetery was found at Covent Garden. This showed that new settlers were living there as early as the 500s, or even the 400s. Their main settlement, called Lundenwic, was outside the Roman walls, a short distance west along what is now the Strand. This name meant "London trading settlement." Recent digs show that this early Anglo-Saxon London was well-organized, with streets laid out in a grid, and likely had 10,000 to 12,000 people.

Early Anglo-Saxon London was home to the "Middle Saxons," who gave their name to the county of Middlesex. By the early 600s, the area was part of the kingdom of the East Saxons. In 604, King Saeberht of Essex became Christian, and London got its first bishop after the Romans, named Mellitus.

At this time, King Æthelberht of Kent was powerful, and he helped Mellitus build the first St. Paul's Cathedral. It was probably a small church and might have been destroyed when Mellitus was forced to leave. Christianity became permanent in the East Saxon kingdom in the 650s. In the 700s, the kingdom of Mercia took control of southeastern England, including London.

Viking attacks became common in the 800s. London was attacked in 842 and again in 851. The Danish "Great Heathen Army" stayed in London in 871. The city was held by the Danes until 886, when King Alfred the Great of Wessex captured it. He put his son-in-law, Æthelred, in charge.

Around this time, people moved back inside the old Roman walls for safety, and the city was called Lundenburh. The Roman walls were fixed, and the defensive ditch was dug again. A bridge was likely rebuilt too. A second fortified area was set up on the south bank at Southwark. The old settlement of Lundenwic became known as the ealdwic or "old settlement," which is why we have the name Aldwych today.

From this point, the City of London started to develop its own local government. London became more important for government because of its size and wealth, even though Winchester was the traditional center. King Athelstan held many important meetings in London.

Viking attacks started again in the late 900s. In 994, King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark attacked London but failed. In 1013, London was the last place in England to resist the Danes, but it eventually gave in. Sweyn died soon after, and King Æthelred returned. But Sweyn's son, Cnut, attacked again in 1015.

After Æthelred died in London in 1016, his son Edmund Ironside became king. Cnut then besieged London, but Edmund's army saved the city twice. After a defeat, Edmund gave Cnut all of England north of the Thames, including London. When Edmund died, Cnut controlled the whole country.

A Norse story tells of a battle where King Æthelred attacked Danish-held London. The story says the Danes on London Bridge threw spears at the attackers. But the attackers used roofs from nearby houses as shields in their boats. This allowed them to get close enough to pull the bridge down with ropes, ending the Viking control of London. This story might be about Æthelred's return in 1014.

After Cnut's family line ended in 1042, English rule returned under Edward the Confessor. He founded Westminster Abbey and spent much of his time at Westminster. From this time, Westminster slowly became the center of government, taking over from the City of London. Edward's death in 1066 led to a fight over who would be king and the Norman conquest of England.

Harold Godwinson was chosen as king and crowned in Westminster Abbey. But he was defeated and killed by William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy at the Battle of Hastings. The English leaders in London then chose Edward's young nephew, Edgar the Ætheling, as king.

The Normans advanced towards London. They defeated an English attack and burned Southwark but couldn't cross the bridge. They went upstream, crossed the river at Wallingford, and then approached London from the northwest. The English leaders decided to give up. The main citizens of London, along with church and noble leaders, surrendered to William at Berkhamsted. William then entered London and was crowned king in Westminster Abbey.

Norman and Medieval London: Castles and Changes (1066 – Late 1400s)

The new Norman rulers built strong forts in London to control the people. The most important was the Tower of London at the east end of the city. Its first wooden fort was quickly replaced by England's first stone castle. Smaller forts were also built along the river. King William also gave London a charter in 1067, confirming its existing rights and laws. London became a center for England's first Jewish population, who arrived around 1070. The city gained more self-rule with election rights given by King John in 1199 and 1215.

In 1091, a powerful tornado hit London, damaging churches and over 600 houses. It also hit London Bridge, which was later rebuilt in stone.

In 1097, William Rufus, William the Conqueror's son, started building 'Westminster Hall'. This became a key part of the Palace of Westminster.

In 1176, work began on the most famous London Bridge, finished in 1209. This bridge, built on the site of older wooden ones, lasted 600 years and was the only bridge across the River Thames until 1739.

In 1216, during a civil war, Prince Louis of France occupied London. He was supported by rebels against King John. However, after John's death, Louis's supporters switched sides to John's son, Henry III, and Louis had to leave England.

London's Jewish community faced difficulties and was eventually forced to leave England by Edward I in 1290. They went to France, Holland, and other places.

Over the next centuries, London became less influenced by French culture. The city played a big part in the development of the English language we speak today.

Trade grew steadily in the Middle Ages, and London became much bigger. In 1100, London had just over 15,000 people. By 1300, it had grown to about 80,000. London lost at least half its population during the Black Death in the mid-1300s. But its importance helped it recover quickly, even with more sicknesses. Trade in London was run by different guilds, which controlled the city and elected the Lord Mayor of the City of London.

Medieval London had narrow, winding streets. Most buildings were made of wood and straw, which meant fires were a constant danger. City sanitation was also very poor.

During the Peasants' Revolt in 1381, rebels led by Wat Tyler invaded London. They stormed the Tower of London and executed important officials. The peasants looted the city and set many buildings on fire.

London's Modern History

Tudor London: Growth and Change (1485–1604)

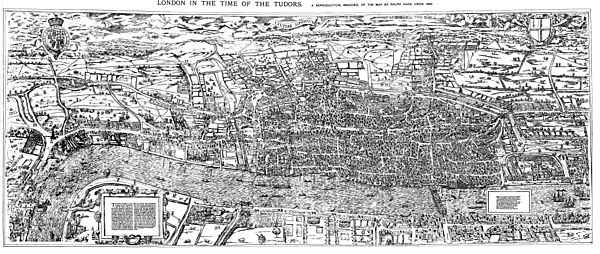

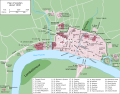

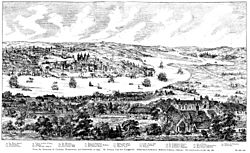

| Wyngaerde's "Panorama of London in 1543" | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

During the English Reformation, London became the main center for Protestantism in England. Its strong trade links with Protestant areas in Europe, many foreign merchants, and its role as a printing hub helped new religious ideas spread. Before the Reformation, more than half of London was owned by monasteries and other religious groups.

Henry VIII's "Dissolution of the Monasteries" greatly changed the city as most of this property changed hands. For example, the Charterhouse became private property.

London quickly became more important among Europe's trading centers. Trade grew beyond Western Europe to places like Russia, the Middle East, and the Americas. Big trading companies like the Muscovy Company (1555) and the British East India Company (1600) were started in London. The East India Company, which eventually ruled India, was very important for London and Britain for 250 years.

Many people moved to London, not just from England and Wales, but also from other countries, like Huguenots from France. The population grew from about 50,000 in 1530 to around 225,000 in 1605. This growth was helped by a huge increase in shipping along the coast.

The late 1500s and early 1600s saw a great time for plays in London, with William Shakespeare being the most famous writer. By the time Elizabeth I died in 1603, London was still quite compact.

There was a lot of distrust towards foreigners in London, which grew after the 1580s. Many foreigners, especially Dutch and German workers and traders, left London for more welcoming cities. By 1600, foreigners made up about 4,000 of London's 100,000 residents.

Stuart London: Plague, Fire, and Rebuilding (1603–1714)

London's growth beyond the City's old borders really took off in the 1600s. In the early part of the century, areas just outside the City were not considered healthy. For example, Moorfields to the north was a place for beggars and travelers.

When King James I became king, a severe plague epidemic hit, killing over 30,000 people. The Lord Mayor's Show was brought back in 1609. The old Charterhouse monastery was bought by Thomas Sutton for £13,000. New buildings for a hospital, chapel, and school were started in 1611. Charterhouse School became one of London's main public schools until it moved to Surrey later.

During the day, Londoners often met in the main hall of Old St. Paul's Cathedral. Merchants did business there, lawyers met clients, and people looked for work. St Paul's Churchyard was the center of the book trade, and Fleet Street was known for entertainment. Plays became even more popular under James I.

Charles I became king in 1625. During his rule, rich people started living in the West End. More and more wealthy families lived in London for part of the year just for social life. This was the start of the "London season." New areas like Lincoln's Inn Fields (around 1629) and Covent Garden (around 1632), designed by Inigo Jones, were built. Nearby streets were named after members of the royal family.

In January 1642, five members of parliament, whom the King wanted to arrest, found safety in the City. In August, the King started the English Civil War. London supported the parliament. The King won a battle near London, but the City quickly formed a new army, and Charles retreated.

After this, a large system of defenses was built to protect London from royalist attacks. This included strong earth walls with forts. It went far beyond the City walls and covered the whole urban area, including Westminster and Southwark. London was not seriously threatened by the royalists again, and the City's money greatly helped parliament win the war.

London, being crowded and not very clean, suffered from many outbreaks of the plague over the centuries. The last major outbreak in Britain was the "Great Plague" in 1665 and 1666. It killed about 60,000 people, which was one-fifth of the population. Samuel Pepys wrote about the epidemic in his diary. On September 4, 1665, he wrote that over 7,400 people died in one week, with about 6,000 from the plague, and all he heard day and night were church bells ringing for the dead.

The Great Fire of London (1666)

The Great Plague was followed by another disaster, which actually helped end the plague. On Sunday, September 2, 1666, the Great Fire of London started at 1 AM in a bakery on Pudding Lane. A strong east wind spread the fire quickly. Efforts to stop it by pulling down houses were disorganized at first. The wind died down on Tuesday night, and the fire slowed on Wednesday. By Thursday, it was out, but then flames burst out again at the Temple. Some houses were blown up with gunpowder, and the fire was finally controlled. The Monument was built to remember the fire.

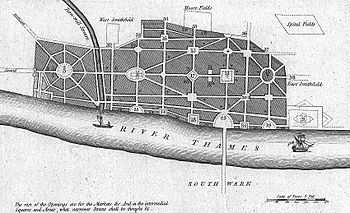

The fire destroyed about 60% of the City, including Old St Paul's Cathedral, 87 churches, and many company halls. Surprisingly, very few people died, perhaps only 16. Within days, three plans were given to the king for rebuilding the city, by Christopher Wren, John Evelyn, and Robert Hooke.

Wren wanted to build wide, straight streets, put churches in clear spots, create large public squares, and make a nice quay along the river. However, these plans were not used. The rebuilt city mostly followed the old street plan, much of which is still there today.

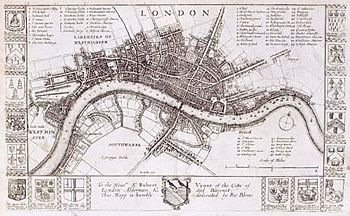

Still, the new City was different. Many rich residents never returned, preferring new homes in the West End, where fashionable areas like St. James's were built near the royal palaces. This made a clear separation between the middle-class trading City of London and the aristocratic world of the court in Westminster.

In the City itself, buildings changed from wood to stone and brick to prevent future fires. A law stated that building with brick was "more comely and durable, but also more safe against future perils of fire." Only doorframes, window frames, and shop fronts could still be made of wood.

Christopher Wren's big plan for London didn't happen, but he was chosen to rebuild the destroyed churches and St Paul's Cathedral. His domed baroque cathedral became London's main symbol for over a century. Robert Hooke, as city surveyor, oversaw the rebuilding of houses. The East End, just east of the city walls, also became very populated after the Great Fire. London's docks grew downstream, attracting many workers who lived in poor conditions.

In the winter of 1683–1684, the River Thames froze so hard that a "frost fair" was held on it. Many Huguenots moved to London after 1685, starting a silk industry in Spitalfields.

At this time, the Bank of England was founded, and the British East India Company grew. Lloyd's of London also started. By 1700, London handled most of England's trade, especially luxury goods from the Americas and Asia like silk, sugar, tea, and tobacco. London was a huge trading and distribution center.

William III didn't like London's smoke, so he bought Nottingham House and turned it into Kensington Palace. This helped Kensington grow. Greenwich Hospital was also started. During Queen Anne's reign, a law was passed to build 50 new churches for the growing population outside the City.

18th Century London: A Growing Empire's Heart (1700s)

The 1700s were a time of fast growth for London. This was due to more people living in the country, the start of the Industrial Revolution, and London's role as the center of the growing British Empire.

In 1707, England and Scotland joined to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. A year later, in 1708, Christopher Wren's amazing St Paul's Cathedral was finished. This cathedral replaced the one destroyed by the Great Fire and is a beautiful example of Baroque architecture.

Many traders from different countries came to London, making it a bigger and busier city. Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War opened up new markets, boosting London's wealth even more.

During the Georgian period, London spread out quickly. New areas like Mayfair were built for the rich in the West End. New bridges over the Thames helped development in South London and the East End. The Port of London also expanded downstream.

In 1762, King George III bought Buckingham Palace (then called Buckingham House). It was made much bigger over the next 75 years.

Coffeehouses became popular places to discuss ideas. With more people able to read and the printing press improving, news became widely available. Fleet Street became the center of the growing newspaper industry.

Crime was a problem in 18th-century London. The Bow Street Runners were set up in 1750 as a professional police force. Punishments for crimes were very harsh, with the death penalty used for even small offenses. Public hangings were common and popular events.

In 1780, London saw the Gordon Riots, an uprising by Protestants against rights for Catholics. Churches and homes were badly damaged, and many rioters were killed.

Until 1750, London Bridge was the only way to cross the Thames. But in that year, Westminster Bridge opened, giving London Bridge a rival. In 1798, a banker named Nathan Mayer Rothschild started a banking house in London. His family's bank helped finance many big projects, like railways around the world.

The 18th century saw London grow and change a lot, leading into modern times.

19th Century London: A Global Powerhouse (1800s)

In the 1800s, London became the world's largest city and the capital of the British Empire. Its population grew from 1 million in 1800 to 6.7 million a century later. During this time, London became a global center for politics, money, and trade. It was mostly unmatched until the late 1800s, when Paris and New York started to catch up.

While London became very wealthy, it was also a city of poverty. Millions lived in crowded and unhealthy slums. Life for the poor was famously described by Charles Dickens in books like Oliver Twist.

In 1829, Robert Peel created the Metropolitan Police force to cover the whole city. The police officers became known as "bobbies" or "peelers" after him.

The 1800s also saw London transformed by railways. A new network of trains allowed suburbs to grow in nearby areas. Middle-class and wealthy people could live there and travel to the city center for work. This led to London's massive outward growth. However, it also made the class divide worse, as richer people moved to the suburbs, leaving poorer people in the inner city.

The first railway in London, from London Bridge to Greenwich, opened in 1836. Soon after, big train stations like Euston (1837), Paddington station (1838), and King's Cross (1850) opened, connecting London to all parts of Britain. From 1863, the first lines of the London Underground (the Tube) were built.

The city continued to grow rapidly. By the mid-1800s, London's old local government struggled with the fast population growth. In 1855, the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was created to improve London's infrastructure. One of its first jobs was to fix London's sanitation problems. At the time, raw sewage was dumped directly into the River Thames. This led to "The Great Stink" of 1858.

Parliament finally allowed the MBW to build a huge system of sewers. Joseph Bazalgette was the engineer in charge. In one of the biggest civil engineering projects of the 1800s, he oversaw the building of over 2,100 kilometers (1,300 miles) of tunnels and pipes under London to remove sewage and provide clean drinking water. When the London sewerage system was finished, deaths in London dropped sharply, and diseases like cholera were stopped. Bazalgette's system is still used today.

One of the most famous events of 19th-century London was the Great Exhibition of 1851. Held at The Crystal Palace, this fair attracted 6 million visitors from around the world. It showed Britain at the peak of its power as an empire.

As the capital of a huge empire, London attracted immigrants from colonies and poorer parts of Europe. Many Irish people settled in the city during the Victorian period, with many coming as refugees from the Great Famine (1845–1849). At one point, Catholic Irish made up about 20% of London's population, often living in crowded slums. London also became home to a large Jewish community, known for their work in clothing and trade.

In 1888, the new County of London was created, run by the London County Council. This was the first elected body to govern all of London. The County of London covered most of the city's built-up area at the time. In 1900, the county was divided into 28 metropolitan boroughs for more local administration.

Many famous London buildings and landmarks were built in the 1800s, including:

- Trafalgar Square

- Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament

- The Royal Albert Hall

- The Victoria and Albert Museum

- Tower Bridge

20th Century London: Wars and Modernization (1900s)

Early 20th Century (1900–1939)

London entered the 20th century at the height of its power as the capital of one of the largest empires. But the new century brought many challenges.

London's population kept growing fast in the early 1900s. Public transport greatly expanded. A large tram network was built, and the first motorbus service started in the 1900s. Improvements were made to London's overground and underground rail networks, including major electrification.

During World War I, London was bombed for the first time by German zeppelin airships. These raids killed about 700 people and caused great fear. The largest explosion in London during World War I was the Silvertown explosion, when a factory with 50 tons of TNT exploded, killing 73 people.

The time between the two World Wars saw London's size grow faster than ever. People preferred living in lower-density suburban homes, often semi-detached houses, seeking a more "rural" lifestyle. This was made possible by the expanding rail network, including trams and the Underground, and slowly increasing car ownership. London's suburbs spread beyond the County of London into nearby counties.

Like the rest of the country, London suffered from high unemployment during the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the East End, extreme political parties gained support. Clashes between these groups led to the Battle of Cable Street in 1936. London's population reached its highest point ever in 1939, with 8.6 million people.

Many Jewish immigrants fleeing Nazi Germany settled in London during the 1930s, mostly in the East End.

Herbert Morrison, a Labour Party politician, was a very important figure in London's local government in the 1920s and 1930s. He unified the bus, tram, and trolleybus services with the Underground by creating the London Passenger Transport Board (known as London Transport) in 1933. He also led efforts to build the new Waterloo Bridge and designed the Metropolitan Green Belt around the suburbs.

London in World War II

During World War II, London, like many other British cities, was heavily bombed by the German Luftwaffe in what was called The Blitz. Before the bombings, hundreds of thousands of children were sent from London to the countryside for safety. Civilians took shelter from air raids in underground stations.

The heaviest bombing happened during The Blitz between September 7, 1940, and May 10, 1941. London was attacked 71 times, receiving over 18,000 tons of explosives. One raid in December 1940, known as the Second Great Fire of London, caused a huge fire that destroyed many historic buildings in the City of London. However, St Paul's Cathedral remained standing, and a photo of it surrounded by smoke became a famous image of the war.

After failing to defeat Britain, Hitler focused on the Eastern Front, and regular bombing raids stopped. They started again, but on a smaller scale, in early 1944. Towards the end of the war, in 1944-45, London was attacked heavily by pilotless V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets, fired from Nazi-occupied Europe. These attacks ended when Allied forces captured their launch sites.

London suffered severe damage and many deaths. The Docklands area was hit the worst. By the end of the war, almost 30,000 Londoners had been killed by bombings, and over 50,000 were seriously injured. Tens of thousands of buildings were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of people lost their homes.

Post-War London (1945–2000)

Three years after the war, the 1948 Summer Olympics were held at the original Wembley Stadium. London had barely recovered from the war at this time. Rebuilding was slow to start. However, in 1951, the Festival of Britain was held, which brought a new feeling of hope and looking to the future.

In the years right after the war, housing was a big problem because so many homes had been destroyed. Authorities decided to build tall blocks of flats to solve the housing shortage.

Through the 1800s and early 1900s, Londoners used coal for heating, which created a lot of smoke. This caused frequent "pea-souper" fogs. The Clean Air Act 1956 was passed, creating "smokeless zones" where only "smokeless" fuels could be used.

Starting in the mid-1960s, London became a center for worldwide youth culture. This was partly due to the success of British musicians like the Beatles and The Rolling Stones. The "Swinging London" subculture made Carnaby Street famous for youth fashion around the world.

From the 1950s onwards, London became home to many immigrants, mostly from Commonwealth countries like Jamaica, India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. This greatly changed London, making it one of Europe's most diverse cities.

From the early 1970s until the mid-1990s, London faced repeated terrorist attacks by the Provisional IRA.

London's role as a major port declined sharply after the war. The old Docklands couldn't handle large modern container ships. The main ports for London moved further downstream. The Docklands area became mostly empty by the 1980s, but it was redeveloped into flats and offices from the mid-1980s. The Thames Barrier was finished in the 1980s to protect London from tidal surges from the North Sea.

21st Century London: A Modern Metropolis

Around the start of the 21st century, London hosted the Millennium Dome at Greenwich to mark the new century. Other Millennium projects were more successful. One was the London Eye, the world's largest observation wheel. It was meant to be temporary but became a permanent landmark, attracting millions of visitors each year. The National Lottery also provided a lot of money for improvements to existing attractions, like putting a roof over the Great Court at the British Museum.

The London Plan, published in 2004, predicted that London's population would reach 8.1 million by 2016 and keep growing. This led to more dense, urban building styles, including many tall buildings. There were also plans for big improvements to public transport.

On July 6, 2005, London won the right to host the 2012 Olympics and Paralympics, making it the first city to host the modern games three times. However, celebrations were cut short the next day when the city was hit by a series of terrorist attacks. More than 50 people were killed and 750 injured in three bombings on London Underground trains and a fourth on a double-decker bus.

London was the starting point for countrywide riots in August 2011. Thousands of people rioted in several city areas and towns across England. These were the biggest riots in modern English history. In 2011, London's population grew to over 8 million people for the first time in decades. For the first time, people of White British background made up less than half of the population.

There was some mixed public feeling before the 2012 Summer Olympics in the city. But public opinion changed greatly in favor of the games after a successful opening ceremony, and when the expected transport problems didn't happen.

Boris Johnson was elected mayor of London in 2008 and re-elected in 2012. He was followed by Sadiq Khan, who became the first Muslim mayor of a major Western capital city in 2016. Khan was re-elected in 2021 and won a historic third term in 2024.

In the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, London was the only region in England where more people voted to remain in the European Union. However, Britain's exit from the EU in early 2021 (Brexit) only slightly weakened London's position as an international financial center.

In 2022, the Elizabeth line railway opened. It connects Heathrow and Reading to Shenfield and Abbey Wood through a new tunnel under the city. This has greatly improved east-west travel in London.

On May 6, 2023, the coronation of Charles III and his wife, Camilla, as king and queen of the United Kingdom, took place at Westminster Abbey in London.

As of May 9, 2023, London had welcomed around 18,000 refugees from Ukraine due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

London's Population Over Time

| Year | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–A few farmers | |

| 50 | 50–100 |

|

| 140 | 45–60,000 |

|

| 300 | 10–20,000 |

|

| 800 | 10–12,000 |

|

| 1000 | 20–25,000 |

|

| 1100 | 10–20,000 |

|

| 1200 | 20–25,000 |

|

| 1300 | 80–100,000 |

|

| 1350 | 25–50,000 |

|

| 1500 | 50–100,000 |

|

| 1550 | 120,000 |

|

| 1600 | 200,000 |

|

| 1650 | 350,000–400,000 |

|

| 1700 | 550,000–600,000 |

|

| 1750 | 700,000 |

|

| 1801 | 959,300 |

|

| 1831 | 1,655,000 |

|

| 1851 | 2,363,000 |

|

| 1891 | 5,572,012 |

|

| 1901 | 6,506,954 |

|

| 1911 | 7,160,525 |

|

| 1921 | 7,386,848 |

|

| 1931 | 8,110,480 |

|

| 1939 | 8,615,245 |

|

| 1951 | 8,196,978 |

|

| 1961 | 7,992,616 |

|

| 1971 | 7,452,520 |

|

| 1981 | 6,805,000 |

|

| 1991 | 6,829,300 |

|

| 2001 | 7,322,400 |

|

| 2006 | 7,657,300 |

|

| 2011 | 8,174,100 |

|

| 2015 | 8,615,246 |

|

Famous Historical Sites in London

- Alexandra Palace

- Battersea Power Station

- Buckingham Palace

- Croydon Airport

- Hyde Park

- Monument to the Great Fire of London

- Palace of Westminster

- Parliament Hill

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich

- St Paul's Cathedral

- Tower Bridge

- Tower of London

- Tyburn

- Vauxhall station

- Waterloo International station

- Westminster Abbey

Images for kids

-

A Carausius coin from Londinium mint

-

A medal of Constantius I capturing London (inscribed as lon) in 296 after defeating Allectus. From Beaurains treasure.

-

A silver coin of Alfred, with the legend ÆLFRED REX

-

The statue of Alfred the Great at Winchester, erected 1899

-

A plaque in the City of London noting the re-establishment of the Roman walled city

-

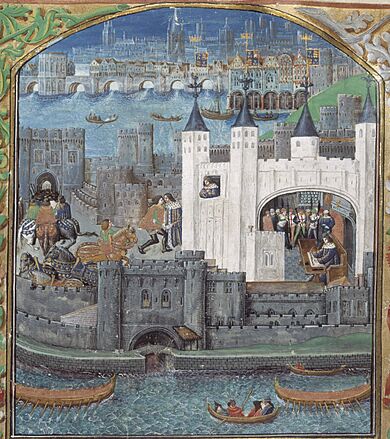

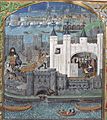

A depiction of the imprisonment of Charles, Duke of Orléans in the Tower of London, from a 15th-century manuscript. Old London Bridge is in the background

-

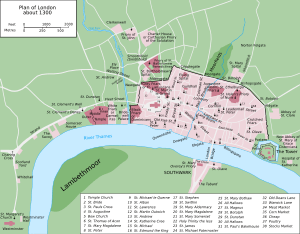

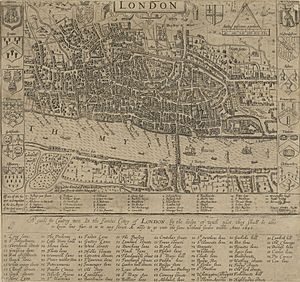

John Norden's map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

-

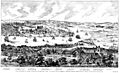

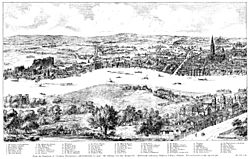

A panorama of London by Claes Jansz. Visscher, 1616. Old St Paul's Cathedral had lost its spire by this time. The two theatres on the foreground (Southwark) side of the Thames are The Bear Garden and The Globe. The large church in the foreground is St Mary Overie, now Southwark Cathedral.

-

Samuel Pepys, chronicler of Stuart London

-

John Evelyn's plan for the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire

-

Richard Blome's map of London (1673). The development of the West End had recently begun to accelerate.

-

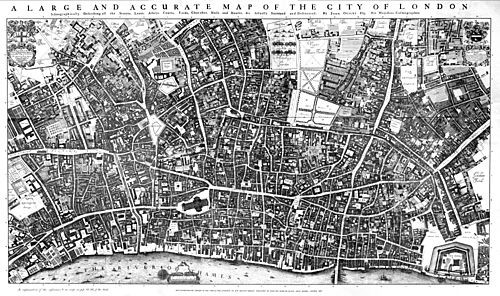

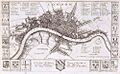

Ogilby & Morgan's map of the City of London (1673). "A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London. Ichnographically describing all the Streets, Lanes, Alleys, Courts, Yards, Churches, Halls, & Houses &c. Actually Surveyed and Delineated by John Ogilby, His Majesties Cosmographer."

-

The Clock Tower of Wren's St Paul's Cathedral

-

Buckingham Palace as it appeared in the 17th century

-

Buckingham Palace in 1837, enlarged by John Nash

-

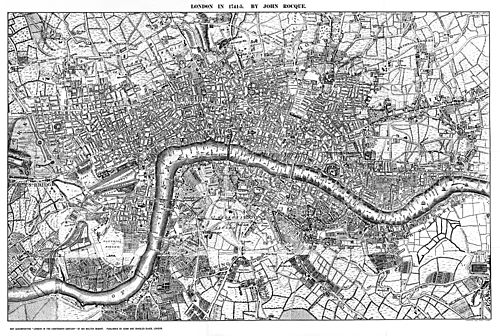

A detailed copy of John Rocque's Map of London, 1741–5

-

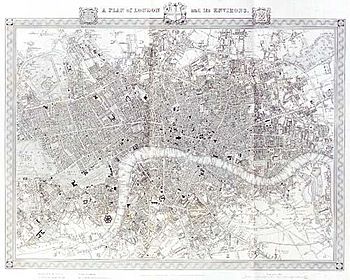

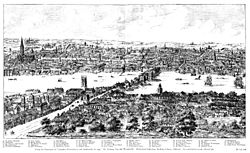

London as engraved by J. & C. Walker in 1845 from a map by R Creighton. Many districts in the West End were fully developed, and the East End also extended well beyond the eastern fringe of the City of London. There were now several bridges over the Thames, allowing the rapid development of South London.

-

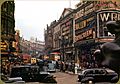

Cheapside pictured in 1909, with the church of St Mary-le-Bow in the background.

-

Firefighters putting out flames at a bomb site during The Blitz, 1941.

-

The Shard (left), an icon of 21st-century London

-

People gathered in Whitehall to hear Winston Churchill's victory speech, 8 May 1945.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Londres para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Londres para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |