English coffeehouses in the 17th and 18th centuries facts for kids

In the 1600s and 1700s, English coffeehouses were popular public places. Men would gather there to chat, share news, and do business. For just one penny, you could buy a cup of coffee and get in.

Coffee first came to England in the mid-1600s. Before that, people mostly used it as medicine. These coffeehouses also served tea, hot chocolate, and small meals.

Historian Brian Cowan says coffeehouses were "places where people gathered to drink coffee, learn the news of the day, and perhaps to meet with other local residents and discuss matters of mutual concern." People could talk about important topics like the Yellow Fever. The atmosphere was more serious than in a pub. Coffeehouses also helped create financial markets and newspapers.

People discussed many things, including politics, gossip, fashion, and new ideas in science and philosophy. Historians often connect English coffeehouses to the Age of Enlightenment. They were like another place for learning, similar to a university. Political groups often met there too.

How Coffeehouses Began

Coffee Comes to Europe

Europeans first learned about coffee from stories of travelers visiting countries in Asia. These travelers described a "black drink" made from a special plant that grew in Arabia. They said people drank it all day and night. It kept them awake and alert, helping them talk and argue without getting tired.

Historian Brian Cowan explains how Europeans took this new idea of drinking coffee and made it their own. They changed it to fit their traditions. For example, important English thinkers, called virtuosi, studied coffee. Sir Francis Bacon was one of them. He wanted to learn about the natural world. His work led to more research into coffee's health benefits.

People thought coffee could cure problems like headaches, gout, and even smallpox. But some people worried about coffee. They feared too much coffee could cause tiredness, paralysis, heart problems, and shaking.

Oxford's First Coffeehouses: "Penny Universities"

By the mid-1600s, coffee was no longer just seen as medicine. This opened the door for new places to serve it. The city of Oxford was perfect for this, with its many scholars and thinkers.

The very first English coffeehouse opened in 1650 in Oxford. It was at the Angel Coaching Inn and run by a man named Jacob. Oxford became a key place for coffeehouse culture in the 1650s.

These early Oxford coffeehouses were called "penny universities." They offered a different way to learn, outside of formal schools. Many scholars went there to discuss new ideas. For just a penny, you got a cup of coffee, access to newspapers, and lively conversations. Reporters, called "runners," would even go around announcing the latest news.

These places attracted all kinds of people. In a time when class was very important, coffeehouses were special. Anyone with a penny could come in. University students often spent more time there than in class! Cowan said, "The coffeehouse was a place for like-minded scholars to gather, to read, as well as learn from and to debate with each other." It was not a university, but a place for serious talks.

Early Oxford coffeehouses were a bit exclusive, mostly for scholars. Famous visitors included Christopher Wren and John Evelyn. These early coffeehouses helped set the tone for future ones in England. They were different from pubs or taverns. Their goal was to encourage serious discussions on important topics.

London's Early Coffeehouses

The idea of coffeehouses quickly spread from Oxford to London. There, they became very popular in English culture and politics. The first London coffeehouse opened in 1652. It was started by Pasqua Rosée from Smyrna, Turkey. London's second coffeehouse, the Temple Bar, opened in 1656.

At first, London coffeehouses weren't very popular. Other businesses saw them as competition. But their popularity grew when Harrington's Rota Club started meeting at a coffeehouse called the Turk's Head. They debated "politics and philosophy." This club was open to everyone. Its main purpose was polite but lively debate.

Even after the Rota Club was banned, their style of discussion shaped coffeehouse talks for the rest of the 1600s. By the early 1700s, London had more coffeehouses than almost any other city in the world.

The Golden Age of Coffeehouses

What They Were Like

English coffeehouses had a special feel during their most popular time, from 1660 to the late 1700s. They quickly became the "town's latest novelty." Their relaxed mood, low cost, and many locations made them popular. Even after the Great Plague of London in 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666, coffeehouses remained popular. People still visited, though they were more careful about talking to strangers.

English coffeehouses were public places where everyone was welcome, as long as they paid a penny for coffee. Historian Markman Ellis describes the wide variety of men found in a coffeehouse: "Like Noah's ark, every kind of creature in every walk of life (frequented coffeehouses)." This included lawyers, sailors, and scholars. Some historians even said these places were democratic. This was because people from all social classes could talk to each other equally.

Coffeehouse talks were supposed to be polite and civil. Historians debate how important this politeness truly was. Some say it was key to keeping coffeehouses popular. Others, like Brian Cowan, say "civility" meant serious, reasoned debate on important topics. He argues that rules helped keep unwanted people out.

Writers Addison and Steele helped spread politeness through their popular magazines, The Tatler and The Spectator. These magazines aimed to improve English manners. However, some historians point to examples of slang and less polite talk. For instance, Moll King's coffeehouse was known for its "flash" (slang). Because Puritan ideas influenced coffeehouses, alcohol was forbidden. This helped keep conversations sober and respectful. If someone asked for ale, they were told to go to a nearby pub.

Different coffeehouses focused on different topics. This shows how varied English society was. After the monarchy was restored, some coffeehouses, called penny universities, offered lessons in French, Italian, Latin, dancing, fencing, poetry, math, and astronomy. Other coffeehouses were for less scholarly men. Child's coffeehouse, for example, was popular with the clergy and doctors.

Coffeehouse Rules

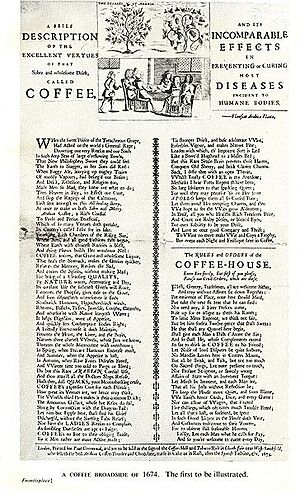

In 1674, a poster called "Rules and Orders of the Coffee House" was printed. It said that everyone was equal in these places. "No man of any station need give his place to a finer man." Historians agree that social status was mostly ignored. Anyone could join a conversation, no matter their class or political views.

If someone swore, they had to pay a twelve-pence fine. If a fight started, the person who started it had to buy the other person a coffee. Talking about "sacred things" was not allowed. Rules also forbade speaking badly about the government or religious texts. Games of chance, like cards and dice, were also banned. However, some historians say these "rules" were more of a joke. They showed that it was hard to control behavior in coffeehouses.

Financial Hubs

Before coffee, most people in England drank watered-down ale or beer. Coffee brought a new era of clear thinking. This helped the economy grow greatly. The stock exchange, insurance companies, and auctions all started in 17th-century coffeehouses. Places like Jonathan's, Lloyd's, and Garraway's became centers for trade and finance. This helped Britain's global trade grow.

At Lloyd's Coffee House, merchants and sailors met to arrange shipping deals. It grew into the famous insurance company Lloyd's of London.

In the 1600s, stockbrokers also met in coffeehouses, especially Jonathan's. They were not allowed in the Royal Exchange because they were considered too rude.

News and Print Culture

English coffeehouses were also key places for news. Historians link them closely to printed and handwritten news. They were important spots for reading and sharing news, and for gathering information. Most coffeehouses offered pamphlets and newspapers, included in the price of admission. Customers could read them at their leisure.

News came in many forms at coffeehouses: printed papers, handwritten notes, and even spoken gossip. "Runners" would go around to different coffeehouses, sharing the latest events. Bulletins announcing sales, ship departures, and auctions were also common.

Richard Steele and Joseph Addison's magazines, The Spectator and The Tatler, were very popular. They were probably the most widely read news and gossip sources in coffeehouses in the early 1700s. Addison and Steele wanted to improve English manners. They did this by telling stories that subtly criticized society. Their stories helped readers choose better ways of acting. They got their news from coffeehouses and then spread their magazines back through them. The good reputation of the press during this time is often linked to the popularity of coffeehouses.

The Enlightenment and New Ideas

Historians debate how much English coffeehouses helped the "public sphere" of the Age of Enlightenment. The Enlightenment was a time when reason became more important than old ways of thinking, like religion or superstition.

According to Jürgen Habermas, the Enlightenment created a public space where people could freely share their ideas. This "public realm" was a place where people could escape their usual roles and think for themselves.

Some historians, like Dorinda Outram, see English coffeehouses as part of an intellectual public sphere. She says they were "commercial operations, open to all who could pay." This meant people from different social classes could hear the same new ideas. Coffeehouses offered newspapers, journals, and books. This helped spread enlightened ideas, especially after more people started reading in the late 1700s.

Historian James Van Horn Melton sees coffeehouses as part of a more political public sphere. He says they "provided public space at a time when political action and debate had begun to spill beyond the institutions that had traditionally contained them." He points out that Harrington's Rota club, which discussed politics, met in a London coffeehouse. This shows coffeehouses were places for political debate. Different political groups used coffeehouses for their own goals. Puritans liked them because alcohol was banned. But royalist critics thought coffeehouses encouraged too much political talk from common people.

Women in Coffeehouses

Historians have different ideas about how much women were involved in English coffeehouses. Some say women were not allowed as customers. Others say that while coffeehouses were open to everyone, conversations were mostly about male topics like politics and business. These topics were not thought to concern women, so their presence was not always welcome.

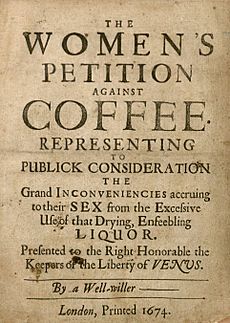

Coffeehouses were often seen as a place for men to talk without women. A lady who wanted to keep her good name would not go there. Because of this, women often complained about coffeehouses. In "The Women's Petition Against Coffee," they argued that coffee made men "unfruitful" and hurt the nation's birth rate. Women also protested that coffeehouses kept husbands away from their homes and duties.

However, women were sometimes allowed in coffeehouses. This happened when they were doing business, or in places like Bath where women were more accepted socially. Women also went to gambling coffeehouses or auctions held there, usually for their households. Historians have also found that female news sellers often entered coffeehouses. These women were not just passively sharing news. They shaped political discussions by knowing what their customers wanted. But even if women worked in coffeehouses, their rank and gender often kept them from fully joining the discussions.

Female owners of coffeehouses, called "coffee-women," were also present. They ran the business and served coffee but usually did not join the conversations. Famous coffee-women included Anne Rochford and Moll King.

Why Coffeehouses Declined

By the late 1700s, coffeehouses had mostly disappeared from England's social scene. Historians give many reasons for this decline.

One reason was that coffeehouse owners tried to control the news. They wanted their own newspaper to be the only source of print news. This idea was met with much ridicule. It hurt the coffee-men's reputation. Historian Markman Ellis explains: "Ridicule and derision killed the coffee-men's proposal but it is significant that, from that date, their influence, status and authority began to wane."

The rise of exclusive clubs also contributed to the decline. The old coffeehouse rules, which made them open to everyone, slowly disappeared. "Snobbery reared its head," Ellis says. Some coffeehouses started charging more than a penny to keep out common people and attract wealthier customers. Literary and political clubs became more popular, as people wanted more serious discussions.

The government's focus on tea also played a role. The British East India Company was more interested in the tea trade than coffee. Competition for coffee had grown around the world. The government encouraged anything that would increase the demand for tea. Tea became fashionable at court, and tea houses, which welcomed both men and women, grew in popularity.

Tea was also easier to prepare. "To brew tea, all that is needed is to add boiling water; coffee, in contrast, required roasting, grinding and brewing." Tea drinking in England grew from 800,000 pounds per year in 1710 to 100,000,000 pounds per year in 1721.

Ellis concludes that coffeehouses had served their purpose. They were no longer needed as places for political or literary debate. They had helped the nation through tough times and set a high standard for writing and criticism.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |