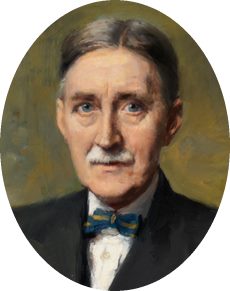

George Dyson (composer) facts for kids

Sir George Dyson (born May 28, 1883 – died September 28, 1964) was a famous English musician and composer. He studied music at the Royal College of Music (RCM) in London. After serving in the First World War, he worked as a school teacher and college lecturer. In 1938, he became the director of the RCM. He was the first former student to lead the college. As director, he made important changes to how the college was run and helped it through the tough times of the Second World War.

As a composer, Dyson wrote music in a classic style. His teachers, Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford, influenced his work. His music was very popular during his lifetime. Later, it was not played as much, but it became popular again in the late 1900s.

Contents

Sir George Dyson's Life and Career

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

George Dyson was born in Halifax, Yorkshire. He was the oldest of three children. His father was a blacksmith and also played the organ and led the choir at a local church. His mother was a weaver, and both parents sang in choirs. They encouraged George's musical talent. When he was 13, he became a church organist. Just three years later, he earned a special music qualification (FRCO, Fellowship of the Royal College of Organists).

In 1900, he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music (RCM). There, he studied how to compose music with Sir Charles Villiers Stanford. To support himself, he worked as an assistant organist at St Alfege Church, Greenwich.

While still a student, he won the Arthur Sullivan prize for composition. In 1904, he received a Mendelssohn Scholarship. This allowed him to travel for three years in Italy, Austria, and Germany. He met important musicians like Richard Strauss. Strauss's style is thought to have influenced Dyson's early music. His piece Siena (1907) was praised by The Times newspaper. Sadly, the music for Siena has been lost.

When he returned to Britain in 1907, Dyson became the director of music at the Royal Naval College, Osborne. This happened because Sir Hubert Parry, the RCM director, recommended him. In 1911, he moved to Marlborough College.

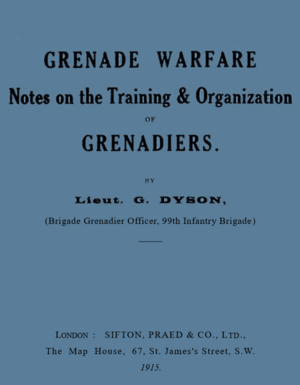

When the First World War started in 1914, Dyson joined the Royal Fusiliers. He became an officer in charge of grenades for an infantry brigade. In this role, he wrote a training guide on grenade warfare, which became well known. In 1916, he became ill from the stress of war (called shell-shock at the time). He was sent back to England. Parry wrote in his diary that Dyson was "a shadow of his former self."

In November 1917, Dyson married Mildred Lucy Atkey. They had a son, Freeman, who became a famous scientist, and a daughter, Alice. In 1917, Dyson earned a DMus degree from the University of Oxford.

After recovering, Dyson became a major in the new Royal Air Force (RAF). He served until 1920. He helped organize RAF bands. He also finished the music for Henry Walford Davies's RAF March Past. He added a slow middle part and arranged the whole piece.

Becoming a Schoolmaster and Professor

In 1920, Dyson's composing career grew. His "Three Rhapsodies for string quartet" were chosen to be published. In 1921, he became the music master at Wellington College and a professor of composition at the RCM. In 1924, he moved to Winchester College while still teaching at the RCM. During this time, he developed his skills as a composer.

Besides teaching at the RCM and Winchester, Dyson also led an adult choir. He was a guest lecturer at the University of Liverpool and University of Glasgow. He had to fit composing into his limited free time.

Some of his works from this period include the cantata In Honour of the City (1928). This piece was described as a strong and lively work for choir and orchestra. It showed his talent for beautiful melodies and clever musical changes. This cantata was so successful that Dyson soon wrote a bigger piece, The Canterbury Pilgrims (1931). This work was based on characters from Chaucer's famous stories. It is probably his most well-known piece.

British music festivals asked Dyson to write new works. For the Three Choirs Festival, he composed St Paul's Voyage to Melita (1933) and Nebuchadnezzar (1935). For the Leeds Festival, he wrote The Blacksmiths (1934). He also wrote orchestral pieces, like a Symphony in G (1937). The Times praised this symphony for being original and not like other music.

In the early 1930s, Dyson worried about the future of amateur music groups in Britain. They faced challenges from the Great Depression and new "mechanical music" like the gramophone and radio. With help, Dyson co-founded the National Federation of Music Societies in 1935. This group helped support music clubs and performing societies.

Leading the Royal College of Music

In 1938, Dyson became the director of the RCM after Sir Hugh Allen retired. He was very proud to be the first former student to lead the college. He got money for the college from the government and set up a pension plan for the staff. He also improved the college's facilities, like rehearsal rooms and bathrooms. He updated the courses and exams. He believed that with great music performances now available on radio and records, musicians needed to be very skilled to succeed. His focus on high standards led to some criticism. The Times said he changed the college's focus from a more general education.

When the Second World War started in 1939, many schools and organizations left London to avoid bombing. Dyson insisted that the RCM stay in South Kensington. His decision was important because other institutions followed his lead. This meant that music training could continue, and standards were kept high. At the RCM, Malcolm Sargent led the college orchestra. Karl Geiringer, a music expert who had to leave Vienna because of the Nazis, joined the teaching staff.

After the war, many students wanted to join the college. Students who had stopped their studies for the war and new applicants made the numbers very high. Dyson and his board had to make the entry requirements stricter. He focused on practical music skills. He even got rid of many old books and manuscripts from the college library, which upset some colleagues.

Dyson sometimes bent the rules to help talented students. For example, Colin Davis, a clarinet student, could not join the conducting class because his piano skills were not good enough. But Malcolm Arnold had better luck. Even though he left the college, Dyson encouraged him to return and made it easier for him. For Julian Bream, Dyson made special arrangements so he could study guitar, which was not usually taught at the college.

Dyson was knighted in 1941 and received another honor (KCVO) in 1953. He also received special degrees from the universities of Aberdeen and Leeds.

In 1952, Dyson retired from the RCM. He moved to Winchester. He continued to compose music, enjoying a "remarkable Indian summer" of creativity. Although his music seemed a bit old-fashioned to some by then, his later works were still published and performed. However, they were not as popular as his earlier music.

Sir George Dyson passed away at his home in Winchester on September 28, 1964, at the age of 81.

Sir George Dyson's Music

Dyson once said about himself as a composer, "My reputation is that of a good technician... not very original. I know modern styles, but they are not what I want to express." A music critic from The Times noted that Dyson's works had a certain mystery. This was because his great musical skill was combined with an outgoing personality. The same writer observed that while all of Dyson's music was well-made, he never developed a truly unique style.

According to his biographer, Paul Spicer, only The Canterbury Pilgrims and two sets of evening church songs are performed often today. Dyson himself chose to list these works as important in his Who's Who entry:

- In Honour of the City (1928)

- The Canterbury Pilgrims (1931)

- St Paul's Voyage (1933)

- The Blacksmiths (1934)

- Nebuchadnezzar (1935)

- Symphony (1937)

- Quo Vadis (1939)

- Violin Concerto (1942)

- Concerto da Camera and Concerto da Chiesa for Strings (1949)

- Concerto Leggiero for Piano and Strings (1951)

- Sweet Thames Run Softly (1954)

- Agincourt (1955)

- Hierusalem (1956)

- Let's go a-Maying (1958)

- A Christmas Garland (1959)

The Dyson Trust also lists other compositions. These include nine orchestral works, seven chamber works, thirteen pieces for piano, four organ pieces, twenty works for chorus and orchestra, and many other choral pieces and songs. Some of his early works have been lost. In 2014, to mark 50 years since his death, a special arrangement of In Honour of the City was created for two pianos and percussion.

Sir George Dyson's Legacy

A music expert named Christopher Palmer helped bring Dyson's music back into public attention. He published books about Dyson in 1984 and 1989. He also helped make the first modern recordings of Dyson's music. The Sir George Dyson Trust was created in 1998. Its goal is to help people understand and enjoy Dyson's music. It also makes his original music papers and writings available for study. Dyson's son, Freeman Dyson, also worked to promote his father's music.

Books by Sir George Dyson

- Grenade Warfare: Notes on the Training and Organisation of Grenadiers (1915)

- The New Music (1924)

- The Progress of Music (1932)

- Fiddling While Rome Burns (1954)

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |