Global cooling facts for kids

Global cooling was an idea, mostly in the 1970s, that the Earth was about to get much colder. Some people thought this cooling could even lead to a new ice age. They believed it would happen because of tiny particles in the air called aerosols or changes in Earth's orbit.

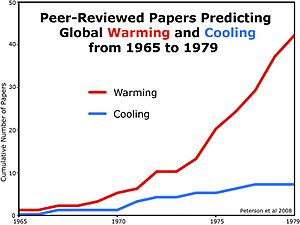

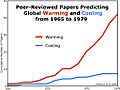

However, many news reports in the 1970s talked about this cooling idea. These reports didn't always show what most scientists were actually thinking. Most scientists at the time were more worried about the Earth getting warmer because of the greenhouse effect.

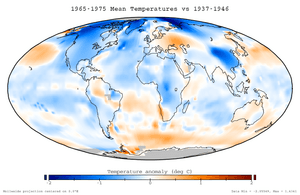

In the mid-1970s, the temperature records available seemed to show that the Earth had been cooling for a few decades. But as scientists got more and better temperature data over longer periods, it became clear that the Earth's overall temperature was actually going up.

Contents

Why People Talked About Global Cooling

In the 1970s, scientists noticed that global temperatures had dropped a bit since 1945. At the same time, they were also starting to understand that gases released by humans could cause the Earth to warm up. When scientists looked at what might happen to the climate in the future, only a small number (less than 10%) thought the Earth would cool. Most predicted future warming.

Most people didn't know much about how carbon dioxide affects the climate. But as early as 1959, a magazine called Science News predicted that carbon dioxide in the air would increase a lot by the year 2000, causing warming. This prediction turned out to be very close to what actually happened.

By the mid-1970s, when the idea of global cooling reached the news, temperatures had actually stopped falling. Scientists were becoming more concerned about the warming effects of carbon dioxide. Because of these worries, the World Meteorological Organization warned in 1976 that "a very significant warming of global climate" was likely.

What Causes Climate Changes?

Scientists now understand that the cooling that happened in the mid-20th century was mostly due to tiny particles called sulfate aerosols. These particles came from burning fossil fuels. In the 1970s, two main ideas were suggested for why the Earth might be cooling: aerosols and changes in Earth's orbit.

Aerosols: Tiny Particles in the Air

When humans burn fossil fuels, like coal and oil, they release tiny particles into the air. These particles are called aerosols. They can affect the climate in two ways:

- Direct effect: Aerosols can reflect sunlight back into space. This means less sunlight reaches the Earth's surface, which can make the planet cooler.

- Indirect effect: Aerosols can also change how clouds form. This can make clouds reflect more sunlight, also leading to cooling.

In the early 1970s, some scientists wondered if this cooling effect from aerosols might be stronger than the warming effect from carbon dioxide. However, with more observations and cleaner ways of burning fuels, scientists now know that global warming is much more likely. Even though aerosols caused some cooling in the past, their effect is now outweighed by the increase in greenhouse gases. Aerosols also contribute to something called global dimming, which means less sunlight reaches the Earth's surface.

Orbital Forcing: Earth's Slow Dance

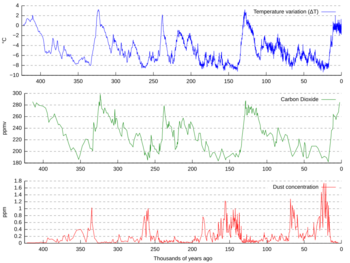

Orbital forcing refers to the very slow, natural changes in how the Earth spins and moves around the Sun. These changes are called Milankovitch cycles. They slightly change how much sunlight reaches different parts of the Earth and affect the strength of the seasons. Scientists believe these cycles are responsible for the timing of past ice ages.

In the 1970s, scientists were learning a lot about these cycles. Some research suggested that the Earth was heading towards another ice age. However, these predictions were about very long-term trends, over thousands of years. They didn't include the effects of human activities, like burning fossil fuels.

The idea that an ice age was coming "soon" became popular. But for geologists, "soon" can mean thousands of years. The fastest orbital cycle takes about 20,000 years. So, a sudden ice age (in less than a century) isn't possible based on these natural cycles alone.

What We Know Now

The idea that temperatures would keep getting cooler, or even speed up, turned out to be wrong. As scientists gathered more and more data, it became clear that the Earth was warming. The IPCC Third Assessment Report in 2001 confirmed this.

Scientists now believe that the current warm period, called an interglacial, will likely continue for tens of thousands of years naturally. Some estimates even suggest it could last for 50,000 years without human influence. In fact, some scientists, like David Archer, have suggested that the current high levels of carbon dioxide will prevent the next ice age from happening for the next 500,000 years. This would make the current warm period the longest in 2.6 million years.

A report from 2015, which included scientist A. Berger, also said that a new ice age is very unlikely to happen within the next 50,000 years. This is true if the amount of carbon dioxide in the air stays above a certain level, which it is doing because of human activities.

In the 1970s, scientists didn't know as much about climate change as they do today. For example, they hadn't yet realized the importance of other greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide. Carbon dioxide was the main human-influenced greenhouse gas studied back then. The attention given to these gases in the 1970s led to many new discoveries in later decades. As the temperature patterns changed, interest in global cooling faded by 1979.

The "Ice Age Fallacy"

Sometimes, people try to argue against the importance of human-caused climate change by saying that scientists were once worried about global cooling, which didn't happen. They then suggest that current worries about global warming are also wrong.

Bryan Walsh, a writer for Time magazine, called this argument "the Ice Age Fallacy." For example, an image of a fake Time magazine cover from 1977, showing a penguin and the title "How to Survive the Coming Ice Age," was shared widely. This fake cover was used to claim that people were just as worried about an ice age in the 1970s as they are about global warming today. However, in 2013, Walsh confirmed that the image was a hoax. It was actually changed from a 2007 Time cover about global warming.

See also

In Spanish: Enfriamiento global para niños

In Spanish: Enfriamiento global para niños

- Anti-greenhouse effect

- Global dimming

- Global warming

- History of climate change science

- Ice age

- Next glacial maximum

- Volcanic winter

Images for kids

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |