Goldfields Water Supply Scheme facts for kids

The Goldfields Water Supply Scheme is a huge pipeline and dam project. It brings fresh water from Mundaring Weir near Perth all the way to towns in Western Australia's Eastern Goldfields, especially Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie. This amazing project started in 1896 and was finished in 1903.

Even today, the pipeline still works! It provides water to more than 100,000 people in over 33,000 homes. It also supplies water to mines, farms, and other businesses.

Contents

Why Water Was Needed

During the early 1890s, thousands of people moved to the very dry desert areas of Western Australia. They were looking for gold! But there wasn't enough water for everyone. It was a big problem that needed a quick solution.

Before the pipeline, people got water from special machines that turned steam into water (condensers), from rain, and sometimes from "water trains" that brought water in. Railway dams were also important to get water for the trains themselves, which traveled to the goldfields.

How the Scheme Began

In the 1890s, not having enough water in Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie was a serious worry for the people living there. On July 16, 1896, the leader of Western Australia, Sir John Forrest, suggested a new law to the Western Australian Parliament. This law would allow the government to borrow a lot of money – £2.5 million – to build the water scheme. The plan was to send a huge amount of water (23,000 kilolitres) every day from a dam on the Helena River near Mundaring to the Goldfields.

The scheme had three main parts:

- The Mundaring Weir: This was a dam built on the Helena River to create a large water storage area.

- A long pipe: This steel pipe was about 760 millimeters (30 inches) wide and stretched 530 kilometers (330 miles) from the dam to Kalgoorlie.

- Pumping stations: There were eight pumping stations and two smaller dams along the route. These stations helped push the water up hills and control its flow.

Building the Pipeline and the Challenges

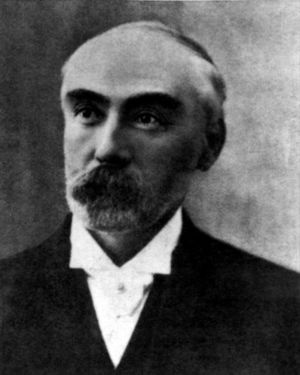

The whole idea for the scheme came from an engineer named C. Y. O'Connor. He was in charge of designing and building most of the project. Even though Premier Forrest supported him, O'Connor faced a lot of criticism. Many people in the Western Australian Parliament and local newspapers thought the engineering task was too big and that it would never work.

There was also a worry that the gold in the area would run out soon. If that happened, the state would be left with a huge debt from building the pipeline, but not enough business to pay it back.

A newspaper editor, Frederick Vosper, often wrote articles that were very critical of O'Connor and his abilities. This happened at a difficult time because Sir John Forrest, who supported O'Connor, had moved into national politics. The new Premier, George Leake, had always been against the scheme.

Sadly, O'Connor died in March 1902, less than a year before the pipeline was fully working.

Lady Forrest, Sir John Forrest's wife, officially started the pumping machines at the first pumping station in Mundaring on January 22, 1903. Just two days later, on January 24, 1903, water finally flowed into the Mount Charlotte Reservoir in Kalgoorlie!

After O'Connor's death, his chief engineer, C. S. R. Palmer, took over and made sure the project was successfully finished. The government later investigated the criticisms and found that O'Connor had done nothing wrong.

The Pipeline Itself

The pipes for the scheme were made right here in Western Australia. They were created from flat steel sheets that came from Germany and the United States. Two companies, Mephan Ferguson and C & G Hoskins, built factories to make the 60,000 pipes needed.

When it was built, this pipeline was the longest freshwater pipeline in the entire world!

The pipeline was built next to the railway lines for parts of its journey. This meant the railway and the pipeline depended on each other in the quiet areas between Southern Cross and Kalgoorlie.

The scheme also needed a lot of power to run the pumping stations. Small towns grew up along the route to help maintain the pipeline and its stations. Today, with better power and modern machines, fewer people are needed to live along the pipeline, as many stations can run by themselves.

The Dam

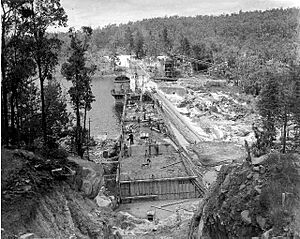

Building the Mundaring Weir dam started in 1898. When it was finished in 1902, it was said to be the highest overflow dam in the world.

After World War II, people decided to make the dam wall even taller. By 1951, its height was increased by 9.7 meters (32 feet).

Old Railway to the Dam

A special railway line, called the Mundaring Weir Branch Railway, was built to help construct the dam. It carried materials from the Mundaring railway station to the building site.

The government railway company later took over running this line. It stopped operating in 1952, and the connecting railway line at Mundaring closed in 1954.

Design Challenges

Building such a long pipeline had many challenges:

- The land suddenly rises a lot between Mundaring and Northam. This meant the second pumping station had to be built very close to the first one.

- The Avon River in Northam caused problems. Pipes laid in the riverbed failed in 1917, so a bridge (the Poole Street Bridge) had to be built to carry the pipeline over the river.

The water also had to be lifted almost 400 meters (1,300 feet) in height. To do this, O'Connor designed eight pumping stations. Each station pumped the water to the next receiving tank.

Early on, there were problems with water leaking from the pipeline. By the early 1930s, a quarter of all the water pumped from Mundaring Weir was leaking out each year!

Pumping Stations

Most of the first pumping stations used steam power, which meant they needed a lot of wood to burn in their boilers. That's why the pipeline route was built close to the railway, which could bring the wood.

To make sure the system was reliable, each pumping station was built with an extra pumping unit. This meant if one broke down, there was a spare. Because of the slope of the pipeline, stations one to four needed two pumping units working at the same time. Stations five to eight only needed one operating pump because the height difference between them was smaller.

Original Pumping Stations

All the first pumping stations used steam power:

- Number One – below Mundaring Weir (now a museum)

- Number Two – above Mundaring Weir (taken down in the 1960s)

- Number Three – Cunderdin (now a museum)

- Number Four – Merredin (this spot has had three different pump stations over time)

- Number Five – Yerbillon

- Number Six – Ghouli

- Number Seven – Gilgai

- Number Eight – Dedari

Current Pumping Stations

Today, there are many more pumping stations along the route:

- Mundaring

- Chidlow

- Wundowie

- Grass Valley

- Meckering

- Cunderdin

- Kellerberrin

- Baandee

- Merredin

- Walgoolan

- Yerbillon

- Nulla Nulla

- Southern Cross

- Ghooli

- Karalee

- Koorarawalyee

- Boondi

- Dedari

- Bullabulling

- Kalgoorlie

Extensions to the main pipeline, called branch mains, started as early as 1907. Water from the pipeline was also used for many country towns near its route, and even reached the Great Southern region. This project began in the 1950s after the dam wall was raised and was finished in 1961.

Celebrating the Scheme

The National Trust of Western Australia created the "Golden Pipeline Project" to help people learn about the scheme. They made guide books, websites, and tourist trails that follow the pipeline and show where the old power stations and towns were. This project started in 1998 and most of the materials were created between 2001 and 2003.

Recent Books and Documentaries

In 2007, two important works about the scheme were produced:

Pipe Dreams

The story of how the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme was built was told in a 2007 documentary called Pipe Dreams. It was part of an ABC TV series called Constructing Australia.

River of Steel

The book River of Steel, written by Dr Richard Hartley, won an award from the State Records Office of Western Australia in 2008.

Lower Helena Dam

The Lower Helena Pumpback Dam is also now used to help supply water to the Goldfields area. Water from this dam is currently pumped back into Mundaring Weir.

Engineering Heritage

The Goldfields Water Supply Scheme is recognized as a very important engineering achievement. It is listed as a National Engineering Landmark by Engineers Australia and an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |