Grand Staircase facts for kids

The Grand Staircase is an amazing series of sedimentary rock layers. These layers stretch across a huge area in the southwestern United States. They go from Bryce Canyon National Park and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument in the north, through Zion National Park, and all the way down to the Grand Canyon. Imagine a giant staircase made of colorful rock layers, each one a step!

Contents

What is the Grand Staircase?

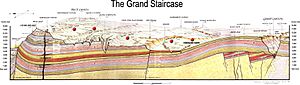

In the 1870s, a geologist named Clarence Dutton first described this area. He saw it as a massive stairway climbing up from the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Each layer's edge formed a huge step. Dutton named five main "steps" based on their colors, starting from the youngest rocks at the top:

- Pink Cliffs

- Grey Cliffs

- White Cliffs

- Vermilion Cliffs

- Chocolate Cliffs

Today, geologists have studied these steps even more closely. They have divided Dutton's big steps into many smaller, specific rock formations.

Here are some of the rock formations found in the Grand Staircase, listed from the youngest (top) to the oldest (bottom):

- Claron Formation

- Kaiparowits Formation

- Wahweap Formation

- Straight Cliffs Formation

- Tropic Shale

- Dakota Sandstone

- Carmel Formation

- Temple Cap Formation

- Navajo Formation

- Kayenta Formation

- Moenave Formation

- Chinle Formation

- Moenkopi Formation

- Kaibab Limestone

- Toroweap Formation

- Coconino Sandstone

- Hermit Shale

- Supai Group

- Surprise Canyon Formation

- Redwall Limestone

- Temple Butte Limestone

- Muav Limestone

- Bright Angel Shale

- Tapeats Sandstone

How the Grand Staircase Formed

The rocks you see in the Grand Staircase are very old. They range from about 200 million to 600 million years old! These layers were laid down over millions of years in warm, shallow seas and along ancient coastlines. The Grand Canyon alone has nearly 40 different rock layers. This makes it one of the most studied geological areas in the world.

The oldest rock layer seen in Zion National Park is the youngest one exposed in the Grand Canyon. This layer is called the Kaibab Limestone and is about 240 million years old. As you move north to Bryce Canyon National Park, you find even younger rocks, some as new as 100 million years old. The oldest rock in Bryce Canyon is the Dakota Sandstone, which is the youngest rock in Zion.

These parks share some rock layers, creating one giant sequence of formations that geologists call the Grand Staircase. The rocks in Bryce Canyon are the youngest known parts of this staircase. Any even younger rocks that might have been there have been worn away by erosion over time.

About 66 million years ago, a process called the Laramide orogeny began. This caused the land to uplift, or rise up, by 5,000 to 10,000 feet (1,500 to 3,000 meters). This uplift made the Colorado River flow faster and cut deeper channels. This created the many plateaus you see in the Colorado Plateau region. The major canyons in the area started to form about five to six million years ago. This happened when the Gulf of California opened up, which lowered the river's base level (the lowest point it can erode to).

Finding Fossils in the Grand Staircase

In the 1880s, many large dinosaur skeletons were found in southern Utah, just north of the Grand Staircase. After these early discoveries, not much exploration happened for a while. However, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, interest in the Grand Staircase's rock layers grew again. Scientists realized that exploring new areas could lead to finding fossils of species never seen before. This is very exciting for young paleontologists (scientists who study fossils) who want to make new discoveries!

displayed at the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument

Click image for display placard text

Southern Utah is a great place to find fossils because of its unique climate. In areas further south, like Arizona, the climate is very dry, so erosion happens slowly. This means fossils stay buried for a long time. Further north, where it's wetter, forests grow. Tree roots and soil bacteria can damage or destroy fossils.

But in southern Utah, there are just enough strong, wet storms to cause quick erosion. This helps expose fossil remains at the surface. At the same time, there isn't enough rain to support deep-rooted plants that could destroy the fossils. This makes it a perfect "sweet spot" for finding ancient life!

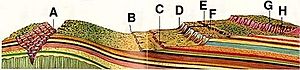

Gallery

(South to north, climbing the staircase)

-

The Permian through Jurassic part of the staircase, as seen at Glen Canyon NRA

See also

In Spanish: Gran Escalinata para niños

In Spanish: Gran Escalinata para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |