Greenwood LeFlore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Greenwood LeFlore

|

|

|---|---|

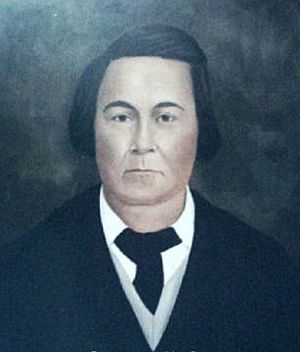

Portrait before 1865

|

|

| Chief of the Choctaw Nation | |

| In office March 15, 1830 – February 24, 1831 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Cole |

| Succeeded by | George W. Harkins |

| Member of the Mississippi Senate and Mississippi House of Representatives | |

| In office 1841–1844 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 3, 1800 Lefleur's Bluff, Territory of Mississippi |

| Died | August 31, 1865 (aged 65) Malmaison, Carroll County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Resting place | Greenwood LeFlore Cemetery, Carroll County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Nationality | Choctaw, American |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouses |

Rosa Donley

(m. 1819; Elizabeth Cody

(m. 1830; Priscilla Donley

(m. 1834; |

| Children | John Donley "Jack" LeFlore , Rebecca Cravat LeFlore Harris, Jane G. LeFlore Spring |

| Parents | Louis LeFleur and Rebecca Cravatt |

| Education | Educated by Major Donly in Nashville, Tenn. |

| Occupation | Politician, planter and entrepreneur |

Greenwood LeFlore (born June 3, 1800 – died August 31, 1865) was an important leader of the Choctaw people. He became the Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation in 1830. Before this, the Choctaw Nation was led by three district chiefs and a council.

LeFlore was a wealthy and powerful Choctaw man. He had family connections to the Choctaw elite through his mother. He also had many friends in the United States government. In 1830, LeFlore and other chiefs signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. This treaty gave the remaining Choctaw lands in Mississippi to the U.S. government. It also meant the Choctaw would move to what was called Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The treaty also said that Choctaw people who wanted to stay in Mississippi could keep their lands. However, the U.S. government did not keep this promise.

Many Choctaw leaders thought moving was unavoidable. But others were against the treaty and even threatened LeFlore. He was later removed from his leadership role by the tribal council. LeFlore chose to stay in Mississippi. He became a U.S. citizen and lived in Carroll County. In the 1840s, he was elected to the state government as a legislator and senator. During the American Civil War, he supported the Union.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Greenwood LeFlore was the first son of Rebecca Cravatt. She was a high-ranking Choctaw woman and the daughter of Chief Pushmataha. His father was Louis LeFleur, a French fur trader and explorer from French Canada. Louis worked for a company based in Spanish Florida.

The Choctaw people followed a matrilineal system. This meant that property and leadership roles were passed down through the mother's family. Because of this, LeFlore gained his important status from his mother's family and clan. By the 1820s, mixed-race children like LeFlore were seen as part of the Choctaw elite. Choctaw chiefs understood that these mixed-race leaders could help them deal with the changing world. They could also help them gain new wealth.

LeFlore received a Euro-American education. This helped him understand and work with the changing world in the American South. When he was twelve, his father sent him to Nashville to be educated by Americans.

Marriages and Children

When LeFlore was 17, he married Rosa Donly in Nashville. He met her there and brought her back to the Choctaw Nation in 1817. After Rosa passed away, he married Priscilla Donly, Rosa's sister.

Greenwood LeFlore had several children. These included Jane, who married William Spring. He also had a son named John Donley LeFlore. Other children were Jackson LeFlore and Greenwood LeFlore (Jr.) from his marriage to Rosa Donly. With Priscilla Donly, he had Rebecca, who married James Clark Harris. He also had Clarissa, who married Chief Edmond Aaron McCurtain.

Working for the Choctaw People

LeFlore became powerful and important within the Choctaw tribe at a young age. This was largely due to his mother's family and his own skills. He worked with other leaders to protect the Choctaw lands. They also tried to adapt to new ways as the U.S. government pushed for their removal.

When LeFlore was 22, he became a chief of the western part of the Choctaw Nation in Mississippi. He is known for ending the Choctaw "blood for blood" law. This old law meant that murders would lead to rounds of revenge.

LeFlore supported a "civilization" program. This program was started by U.S. President George Washington. It encouraged Native Americans to live in permanent homes and farm the land. It also suggested they convert to Christianity and send their children to U.S. schools. After Andrew Jackson became president in 1828, LeFlore encouraged the Choctaw to adopt these new ways. He hoped it would help them keep their lands.

LeFlore once said in 1827 that the Choctaw wanted to become a "civilized Nation." He hoped they would be allowed to rest for a few years. He noted they had been bothered so much for land that they hardly knew what to do.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

Even though the Choctaw were seen as one of the "Five Civilized Tribes", they faced pressure from American settlers. These settlers kept moving onto Choctaw lands. The U.S. government wanted to move the Choctaw to lands west of the Mississippi River.

When Andrew Jackson became president in 1828, he strongly supported moving Native Americans. Many Choctaw leaders believed that moving was unavoidable. They felt they could not fight against it. After the Indian Removal Act was passed in 1830, the chiefs of the western and eastern districts resigned. On March 15, 1830, the Choctaw council elected LeFlore as the principal chief. This was the first time the Choctaw had one central leader. He wrote a treaty and sent it to Washington. He wanted to get the best possible deal for his people.

U.S. representatives came to the Choctaw for a treaty meeting. LeFlore used his strong political power and his position as the head of a united tribe. He worked to get the largest and best areas of land in what would become Indian Territory. He also believed that a part of the treaty, Article XIV, would let some Choctaw stay in Mississippi. He thought moving was going to happen anyway. This was because of the politics and the large number of growing American settlers.

The treaty included rules for Choctaw people who wanted to stay in Mississippi. They could become U.S. citizens.

Here is what Article XIV of the treaty said:

- Any Choctaw head of a family who wanted to stay and become a U.S. citizen could do so.

- They had to tell the U.S. Agent within six months of the treaty being approved.

- They would get a reservation of 640 acres of land.

- They would get half that amount for each unmarried child over ten years old living with them.

- They would get a quarter section for each child under ten years old.

- If they lived on this land and planned to be citizens for five years, they would get full ownership.

- This land would include their current home or part of it.

- People who stayed would not lose their rights as Choctaw citizens. But if they ever moved, they would not get any more payments from the Choctaw Nation.

However, the U.S. agent, William Ward, did not register the Choctaw people who wanted to stay in Mississippi. This made LeFlore's goals for the treaty fail.

Some Choctaw people at the time felt LeFlore had let them down. They thought he could have refused the removal. Mushulatubbee, who had resigned, took back his role as Chief of the Western Division. This division would become the new Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. He rejected many of the "civilizing" changes that the national council had ordered. The Western Division council worked to remove LeFlore from power. They succeeded and elected his nephew, George W. Harkins, in his place.

Historians now believe that leaders like LeFlore were a new generation. They were raised as Choctaw but learned from the changing world. They tried to find a way for their people to survive and thrive. The Choctaw ended up with the largest territory of any tribe that was moved. It was in the fertile, forested area of what is now Oklahoma. LeFlore himself received a land grant in Mississippi for 1,000 acres. This included land for his unmarried children living with him.

Life as a U.S. Citizen

In the 1840s, LeFlore was elected as a representative and senator in Mississippi. He was a well-known figure in Mississippi high society. He was also a personal friend of Jefferson Davis. He served two terms in the state house for Carroll County. Then he was elected by the legislature to be a state senator, serving one term. He became a very rich planter. He owned a huge estate where enslaved people worked on cotton fields.

Malmaison, LeFlore's Home

LeFlore wanted a grand house that showed his status as a wealthy planter. He hired James Harris to design it. LeFlore admired Napoleon Bonaparte and Josephine. So, he had the house designed in a French style. He named his Carroll County home Malmaison. This was after the Château de Malmaison, a famous castle near Paris. LeFlore lived in Malmaison until he died in 1865.

To furnish his mansion, LeFlore brought most of the furniture from France. It was custom-made for him. Silver, glass, and china came in large sets. The drawing room had 30 pieces of solid mahogany furniture. It was finished in real gold and covered in silk fabric. The house had mirrors, tables, and large four-poster beds made of rosewood. These beds had silk and satin canopies. There were also four tapestry curtains showing Napoleon and Josephine's palaces.

Malmaison was one of the most impressive homes in Mississippi. Many people visited it each year from all over the United States. It held memories of Mississippi changing from Native American land to a state.

LeFlore's family lived in the mansion until it was destroyed by a fire in 1942. Only a few pieces of crystal, silver, and some chairs were saved. The horse carriage LeFlore used to visit Andrew Jackson and other officials in Washington, D.C., was saved and is still preserved today.

American Civil War and Death

LeFlore supported the Union during the American Civil War. He was against the idea of states leaving the United States. He died a few months after the war ended, at the age of 65. LeFlore was buried wrapped in the American flag on his estate. Besides the mansion, he left an estate of 15,000 acres and 400 enslaved people. With emancipation, the enslaved people became freedmen. Many of them may have stayed on the plantation to work for his family.

Greenwood LeFlore was a man who connected the Choctaw and American worlds. He owned enslaved people who later became freedmen. He could read and write, and he prayed at religious meetings. But he also led a political system for his people. He provided food, shelter, and education for them. He shared his ideas for the future of the Choctaw people.

See also

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |