Grey-headed flying fox facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Grey-headed flying fox |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Pteropodidae |

| Genus: | Pteropus |

| Species: |

P. poliocephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck, 1825.

|

|

|

|

| Native distribution of Pteropus poliocephalus | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

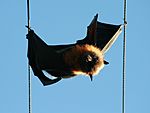

The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is a type of large bat found in Australia. It lives in the south-eastern parts of the country, mainly along the coast. This bat is one of four types of flying foxes that live in mainland Australia. The others are the little red, spectacled, and black flying foxes.

The grey-headed flying fox lives from Bundaberg in Queensland down to Geelong in Victoria. Some smaller groups can be found further north in Ingham and Finch Hatton, and also in Adelaide in the south. This species lives in cooler areas than any other Pteropus bat.

Since 2008, the grey-headed flying fox has been listed as "Vulnerable" on the IUCN Red List, meaning it's at risk of becoming extinct.

Contents

About the Grey-Headed Flying Fox

The grey-headed flying fox is the biggest bat in Australia. Its body is dark grey, and its head is light grey. It has a reddish-brown fur collar around its neck. A special feature of this bat is that it has fur all the way down its legs to its ankles.

Adult bats can have a wingspan of about one metre (3.3 feet). They can weigh up to one kilogram (2.2 pounds). Their weight usually ranges from 600 to 1000 grams (1.3 to 2.2 pounds). The average weight is about 700 grams (1.5 pounds).

Their head and body together are about 23 to 29 centimetres (9 to 11 inches) long. Their forearm length is between 13.8 and 18 centimetres (5.4 to 7.1 inches). Like many large bats, they do not have a tail. They have claws on their first two fingers.

These bats have a "dog-like" face. They do not use echolocation (like sonar) to find their way around. Instead, they use their excellent sense of smell and, mostly, their sight. This is why they have large eyes for a bat. They find their food, like nectar, pollen, and native fruits, using these senses.

Grey-headed flying foxes make many squealing and screeching sounds. When it's hot, they flap their wings to cool down. Blood flows through their wing membranes, which helps release heat from their bodies.

These bats live a long time for their size. Some have lived up to 23 years in zoos. In the wild, they can live up to 15 years.

Where They Live and What They Eat

Where Grey-Headed Flying Foxes Live

These bats live in the eastern parts of Australia. They are usually found within 200 kilometres (124 miles) of the coast. Their range goes from Gladstone in Queensland down to Melbourne in Victoria. They have been moving further south over time.

Cities can sometimes push these bats out of their homes. But cities can also offer new places for them to feed or rest. For example, in Brisbane, many bats live in colonies. In Sydney, you can see them flying through city streets to eat from fig trees in Hyde Park. They have also started to live in Canberra, where they find food from flowering trees.

In the 1920s, studies estimated there were millions of these bats. However, their numbers have gone down a lot since then.

Habitat and Movements

Grey-headed flying foxes live in different places, including rainforests, woodlands, and swamps. They live in large groups called 'camps' or 'roosts'. These camps can have hundreds to tens of thousands of bats. They often move their camps depending on the season. In warmer months, they like cool, wet areas.

Their camps can be in rainforests, melaleuca trees, mangroves, or along rivers. They also set up camps in city areas. For many years, a famous camp was in the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney. However, the bats were moved from there.

The bats move around to find food. Their population is always changing as they follow where certain plants are flowering. They are very important for the environment. They help pollinate over 100 types of native trees and plants. They also spread seeds. Grey-headed flying foxes can fly long distances using the wind. They don't always fly in the same direction. They go wherever they can find the most food.

It wasn't until the 1980s that these bats regularly visited Melbourne. They have had a permanent camp there since the 1990s. Their camp at the Melbourne Botanic Garden caused some debate. The bats were eventually moved to Yarra Bend. This camp was badly affected by a heat wave. The bats were moved again, which led them to find new food sources in the Goulburn Valley. Similarly, a permanent camp was set up in Adelaide in 2010. This spread is likely due to global warming, losing their homes, and dry weather. New camps in cities might be because cities offer a steady food supply (like native trees and fruit trees) and are warmer due to climate change.

Diet and Foraging

Around sunset, grey-headed flying foxes leave their roosts. They can travel up to 50 kilometres (31 miles) each night to find food. They eat pollen, nectar, and fruit from about 187 different plant species. This includes many types of eucalypt trees and fruits from rainforest trees like fig trees.

These bats are important for spreading pollen and seeds. They are the only mammals that eat nectar and fruit in large areas of subtropical rainforests. This makes them very important for these forests.

Flying foxes have special teeth, tongues, and mouths that help them get juice from plants. They hold fruit with their front teeth. They chew the fruit and swallow the juice, spitting out the tough parts. They can carry larger seeds in their mouths and drop them several kilometres away from the tree.

Some plants produce food especially for flying foxes. These plants have flowers and fruits that smell appealing to bats. They are often pale in colour, which bats can see well in low light. The food is also placed away from leaves, making it easier for bats to reach.

Most of the trees these bats eat from produce nectar and pollen at different times of the year. This means the food supply is not always predictable. The bats' ability to migrate helps them find food. The time they leave their roosts to feed depends on how much light there is and the risk of predators. If they leave early, they have more time to find food. However, leaving early also means they are more likely to be caught by predators. Some bats wait for others to leave first, which is called the "after you" effect.

Social Life and Reproduction

Groupings and Territories

Grey-headed flying foxes have two types of camps: summer camps and winter camps. Summer camps are used from September to April or June. In these camps, they set up areas called territories, mate, and have babies. Winter camps are used from April to September. In winter camps, males and females stay in separate areas. They often groom each other. Summer camps are like their main homes, while winter camps are like temporary stops.

In their summer camps, starting in January, male grey-headed flying foxes create mating territories. These territories are usually about 3.5 body lengths long along tree branches. During mating season, the neck glands of males get bigger. They use these glands to mark their territories. Males fight to keep their territories. This fighting can make them lose a lot of body weight.

Around the start of mating season, adult females move towards the central male territories. They join small groups called 'harems' with one male and up to five females. Males in the centre of the camp may have many female partners. Males on the edges of the camp usually have one partner or none. This mating system is called a lek. This means males don't provide resources for the females. Females choose males based on their location in the roost, which shows how strong or healthy the male is.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Mating usually happens between March and May, but most babies are conceived in April. Most mating takes place in the territories during the day. Females have control over the mating process. Males might have to mate with the same female many times. Females usually have one baby each year.

Pregnancy lasts about 27 weeks. Pregnant females give birth between late September and November. Sometimes, babies are born as late as January. The newborn bats are helpless and need their mothers for warmth. For the first three weeks, the young bats cling to their mothers when they go out to find food. After that, the young stay in the roost. By January, young bats can fly well. By February, March, or April, they are fully grown and no longer need their mother's milk.

Threats and Conservation

Threats to Flying Foxes

The grey-headed flying fox faces several dangers. These include losing places to find food and rest, competition with black flying foxes, and large numbers dying because of very hot weather. When they live in cities, people sometimes see them as a problem. They might eat fruit from orchards, but usually only when other food is hard to find.

Because they live and feed in places where humans also live, they sometimes get killed or their roosts are destroyed. People's opinions about these bats have become worse because of three viruses that can be passed to humans: Hendra virus, Australian bat lyssavirus, and Menangle virus. However, only Australian bat lyssavirus is known to pass directly from bats to humans, and only in a few rare cases. No one has died from ABLV after getting the special vaccine.

In the 1970s and 1980s, bats in city camps died from lead poisoning. This lead came from petrol and built up on their fur. When they groomed themselves, they swallowed the lead. The number of deaths from lead dropped after unleaded fuel was introduced in 1985.

Some introduced plants, like the cocos palm, are toxic to these bats and can kill them. The Chinese elm and privet trees also pose this danger. The bats can also get diseases that kill many of them in a camp. Sometimes, many babies are born too early, which can greatly affect the group's numbers. The cause of these problems is not known.

Unsafe netting on backyard fruit trees also kills many bats. This netting can trap them and cause serious injuries or a slow, painful death. This can be avoided by using wildlife-safe netting. Barbed wire fences also cause many deaths. Removing old barbed wire or marking it with bright paint can help.

Since 1994, over 24,500 grey-headed flying foxes have died just from extreme heat events. To help protect them, their roosting sites have been legally protected since 1986 in New South Wales and since 1994 in Queensland. In 1999, the species was listed as "Vulnerable to extinction" in Australia. It is now protected across its range by Australian federal law. As of 2008, it is listed as "Vulnerable" on the IUCN Red List.

In the early 1900s, when flying foxes started visiting orchards, the government offered money for killing them. People thought they destroyed fruit crops, but the damage was often much less than believed. Even after the payments for killing bats stopped, many bats were still shot and wounded. This practice was not effective and harmed the bat population. Now, fruit growers are using netting that also keeps birds away during the day. The widespread killing of bats led to the species being declared vulnerable. This also affected the trees that relied on them for spreading seeds.

Wildlife Rescue Efforts

People who care for bats are specially trained to rescue and help them. They also get vaccinated against rabies. This is because there is a very small chance of catching the rabies-like Australian bat lyssavirus.

Flying foxes often need help from wildlife rescue groups in Australia. They are often found injured, sick, or as orphaned babies. Many adult bats get hurt by getting tangled in barbed wire fences or backyard fruit tree netting. These injuries can be very serious and cause a slow, painful death if the bat is not rescued quickly.

Recently, groups have pushed for laws to make it illegal to use unsafe netting on backyard fruit trees. New wildlife-safe netting has very small holes (5mm x 5mm or less). This allows flying foxes to climb across the netting without getting tangled. It is hoped that using this safe netting will greatly reduce bat injuries.

A growing threat to flying foxes is the increasing number of days when temperatures go above 41 °C (105.8 °F). This causes many bats to die in their camps.

Baby flying foxes usually need help after being separated from their mothers. This often happens when they are 4 to 6 weeks old. They might fall off their mothers during flight because of illness or tick paralysis. Older orphans usually come into care because their mothers died from power line electrocution or barbed wire. Sometimes, many babies are abandoned at once. For example, in November 2008, over 300 baby grey-headed flying foxes were rescued in Queensland.

Most rescued babies are very thirsty and stressed. Some have maggots if they were found sick or hurt. A young flying fox needs to be fed every four hours. As it grows, it starts eating blossoms and fruit. When the young bat is fully grown and no longer needs milk (around 10 to 12 weeks old), it goes into a special 'crèche' (nursery) for rehabilitation. After that, it is released back into the wild.

Gallery

-

Grey-headed flying foxes in Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney

-

Grey-headed flying fox with baby (the smaller bat in the back is a little red flying fox)

- ARKive - images and movies of the grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus)

See also

In Spanish: Pteropus poliocephalus para niños

In Spanish: Pteropus poliocephalus para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |