Henna facts for kids

Henna is a natural reddish-brown dye. It comes from the dried and powdered leaves of the henna plant. People have used it for thousands of years to color hair, skin, and nails. It's especially famous for temporary body art called mehndi, which looks like a beautiful temporary tattoo.

The color from henna gets darker over a few days. Then, it slowly fades as your skin naturally sheds its outer layers. This usually takes about one to three weeks.

Long ago, people in places like Ancient Egypt, the Middle East, and India used henna. They dyed skin, hair, fingernails, and even fabrics like silk and wool. It was popular across West Asia, North Africa, and parts of Africa and India.

The English word "henna" comes from the Arabic word حِنَّاء.

In the U.S., the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has not approved henna for direct use on skin. However, it is allowed as a hair dye.

Contents

A Look at Henna's History

The exact start of human use for henna is not fully known. But we know it was sold in ancient Babylonia. It was also used in Ancient Egypt on some mummies. They used it to dye hair, skin, nails, or even the cloths they were wrapped in.

Henna arrived in North Africa during the Punic civilization. This happened through Phoenician travelers. They used it as a way to make themselves more beautiful. A famous writer named Pliny the Elder wrote about henna's use in the Roman Empire. He said it was used as a medicine, a perfume, and a dye.

How Henna is Prepared and Used

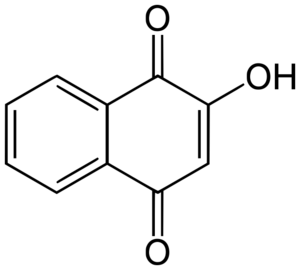

Whole, fresh henna leaves won't stain your skin. This is because the special chemical that causes the stain, called lawsone, is locked inside the plant. But if you dry the leaves and mash them into a paste, they will stain your skin. The lawsone slowly moves from the paste into the outer layer of your skin. It then sticks to the proteins there, creating the stain.

It's hard to make detailed designs with coarsely crushed leaves. So, henna is usually sold as a fine powder. This powder is made by drying, grinding, and sifting the leaves.

Making the Henna Paste

The dry henna powder is mixed with a liquid. This can be water, lemon juice, or strong tea. Other ingredients might be added depending on the tradition. Many artists add sugar or molasses to the paste. This helps it stick better to the skin.

The henna paste needs to sit for a while before use. This can be anywhere from one hour to two days. This resting time allows the lawsone to be released from the leaf bits. The exact time depends on the type of henna plant used.

Some special oils can make the stain better. These include tea tree, cajuput, or lavender oils. Other oils, like eucalyptus and clove, are not used. They can irritate the skin too much.

Applying the Paste

The paste can be put on the skin using many different tools. A simple stick or twig can work. In Morocco, a syringe is often used. In India, people use a plastic cone, similar to those for decorating cakes.

A light stain can appear in just a few minutes. But the longer the paste stays on your skin, the darker and longer-lasting the stain will be. So, it's best to leave it on for as long as possible.

To stop the paste from drying or falling off, people often seal it. They might dab a sugar and lemon mix over the dried paste. Or they might add some sugar directly to the paste. After some time, the dry paste is simply brushed or scraped away. It's best to keep the paste on the skin for at least four to six hours. Many people even wear it overnight.

Do not remove the paste with water. Water can stop the stain from developing fully. Cooking oil can be used to loosen dry paste instead.

Stain Development

When the paste is first removed, henna stains look orange. But over the next three days, they get much darker. They turn into a deep reddish-brown color because of a process called oxidation.

Your palms and the soles of your feet have the thickest skin. This means they absorb the most lawsone. So, stains on hands and feet will be the darkest and last the longest. Some people believe that warming the henna pattern can make the stain darker. This can be done while the paste is still on the skin or after it's removed.

After the stain reaches its darkest color, it stays for a few days. Then, it slowly fades as your skin naturally sheds. This usually happens within one to three weeks.

Storing Henna Paste

Natural henna pastes are made only from henna powder, a liquid, and an essential oil. They don't last long. They can't be left out for more than a week without losing their ability to stain.

The henna plant leaf has a limited amount of lawsone. Once the powder is mixed into a paste, the dye molecules will only be released for about two to six days. If you won't use the paste right away, you can freeze it for up to four months. Freezing stops the dye release. You can then thaw it and use it later.

Some store-bought pastes can stain the skin for longer than seven days without needing to be frozen or refrigerated. These pastes often contain other chemicals besides henna. These chemicals can be harmful to your skin. After about seven days, the natural henna dye is used up. So, any color from these commercial cones after that time comes from other ingredients.

These chemicals are often not listed on the package. They can create many different colors, including natural-looking stains. Some dyes used include sodium picramate. Many of these products might not even contain any real henna.

There are many fake henna pastes sold today. They are often wrongly called "natural," "pure," or "organic." But they contain hidden additives that can be dangerous. Because it takes a long time for pre-made pastes to reach customers, you can guess that any mass-produced cone not shipped frozen might be a harmful chemical mix.

Natural henna only stains the skin one color: a reddish-brown. This color fully develops three days after you apply it.

Fresh henna powder, unlike pre-mixed paste, can be shipped easily worldwide. It can also be stored for many years in a sealed package. Henna powder used for body art is often sifted more finely than henna powders for hair.

Health Effects of Henna

Henna is known to be risky for people with a condition called G6PD deficiency. This condition is more common in males. Babies and children from certain groups, especially from the Middle East and North Africa, are most at risk.

Natural henna paste usually has few negative effects. Sometimes, mild allergic reactions happen. These are often linked to lemon juice or essential oils in the paste, not the henna itself.

However, pre-mixed commercial henna pastes can be dangerous. They might have hidden ingredients added to make the stain darker or change its color. The health risks from these pre-mixed pastes can be serious. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers these risks to be from harmful additives. They are therefore illegal for use on skin.

Some commercial pastes have been found to contain chemicals like:

- p-Phenylenediamine (often called "black henna")

- Sodium picramate

- Amaranth (a red dye banned in the US in 1976)

- Silver nitrate

- Carmine

- Pyrogallol

- Disperse orange dye

- Chromium

These chemicals can cause allergic reactions. They can also lead to long-lasting skin problems or later allergic reactions to hair dyes and fabric dyes.

Images for kids

-

Elderly Punjabi woman whose hair is dyed with henna

-

Mehndi (henna) applied to the back of both hands in India

-

Henna pattern on a foot in Morocco

-

Woman with henna-stained hands in Khartoum, Sudan.

-

Hand of a Bangladeshi Muslim bride on her wedding day

See also

In Spanish: Alheña para niños

In Spanish: Alheña para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |