Historic Cemeteries of New Orleans facts for kids

The Historic Cemeteries of New Orleans in Louisiana, USA, are a special group of forty-two cemeteries. They are important because of their history and culture. These cemeteries are different from most others in the United States. They show a mix of French, Spanish, and Caribbean influences on New Orleans. Also, the city's high water table means bodies cannot be buried deep in the ground. The cemeteries reflect the different groups of people, religions, and wealth levels in the city. Most tombs are above ground, like small houses or buildings. They are often designed in a classic style and laid out like city streets. People sometimes call them “Cities of the Dead.” Some of these historic cemeteries are popular places to visit.

New Orleans is very close to or even below sea level. This means the ground is often wet. If a body or coffin is buried in the ground, it might get waterlogged. It could even float out of the ground! Because of this, people in New Orleans usually bury their loved ones in above-ground tombs. Over time, these tombs have become unique in their design, culture, and history.

Contents

Early History of New Orleans Cemeteries

New Orleans was started in 1718 by the French. It was a tough place to live, with many diseases, storms, and poor sanitation. Many people died, and the city grew fast. So, they needed places to bury the dead very early on.

The first public cemetery was on St. Peter Street in what is now the French Quarter. This was around 1725. Most burials there were in the ground. This was cheaper for the city back then. It closed by 1800. Rich people were often buried inside the St. Louis Church.

In 1788, a yellow fever outbreak hit New Orleans. The old cemetery was too close to homes and the ground was too wet. This caused health problems. So, city leaders created St. Louis Cemetery (now called St. Louis Cemetery Number 1). It was built outside the city walls, which was common in hot places. At first, it was only for Roman Catholics. Protestants could be buried next to it starting in 1804.

The first above-ground tombs appeared in St. Louis Cemetery by 1804. They became common by 1818. When the St. Louis Church became a cathedral in 1794, important people could no longer be buried inside it. They wanted fancy above-ground tombs instead. Also, New Orleans became richer in the early 1800s. Because of these reasons, tombs in St. Louis Cemetery became a way to show off your wealth and importance.

The Bayou St. John Cemetery opened in 1835 for people who died from yellow fever. It was far from the city, making it a safe place for burials during epidemics. It closed by the mid-1840s, and its exact spot is unknown today.

How Burials Happen in New Orleans

When someone needs to be buried in an above-ground tomb, the cemetery worker (called a sexton) opens the outer stone slab. Behind it, there's usually a brick wall that also needs to be removed. The remains of the last person buried there are then put into a bag. They are moved to the very bottom of the tomb. This bottom space is called a "caveau" or "receiving vault." This makes room for the new burial.

By local tradition, a tomb cannot be opened for at least one year and one day. This allows enough time for the previous body to decompose. After the burial ceremony, the sexton rebuilds the brick wall and puts the stone slab back. The names and dates of the deceased are usually carved onto the slab or the tomb. These above-ground tombs are not completely sealed. This allows air to circulate, which helps the body decompose. Even with this tradition, sometimes a year and a day wasn't enough in New Orleans' hot climate. These unique burial practices are still used today.

How Tomb Designs Changed

In the early 1800s, as above-ground tombs became popular, their designs copied ancient Roman styles. Romans believed the afterlife began at the tomb. So, they made tombs grand to honor the dead. Early above-ground tombs were usually brick, much larger than a coffin, and decorated.

Columbaria started appearing in New Orleans in the early 1800s. These are wall structures with many small spaces or niches for individual burials. They helped lower burial costs. People who couldn't afford a big tomb would share resources to build columbaria. These could hold coffins or urns with ashes. Many Benefit societies built these.

As New Orleans grew quickly in the early 1800s, many people who weren't rich needed burial spots. To help with this, "oven tombs" were built. These have vaults or crypts built into a cemetery wall or an above-ground tomb. A body is placed in a vault. In New Orleans' hot, subtropical climate, bodies decompose fast. After about a year, only bones remain. These bones are then moved, often to the ground inside the oven tomb. This frees up the vault for a new burial. Plaques on the tomb remember the deceased. Many people, sometimes dozens, can be buried in one oven tomb. Often, these oven tombs belonged to families.

In 1821, part of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, which was for Protestants, was torn down to build Tremé Street. So, the Girod Street Cemetery opened in 1822 as a dedicated Protestant cemetery. In 1828, the Gates of Mercy Cemetery opened for Jewish burials. Jewish tradition required in-ground burials. So, this cemetery used "copings," which were raised beds for in-ground burials.

By 1830, New Orleans cemeteries had changed from simple burial grounds into beautiful, architecturally unique places. They were laid out like city streets, earning them the name "cities of the dead."

Architects and Masons

J. N. B. de Pouilly's Cemetery Designs

French architect Jacques Nicolas Bussière de Pouilly arrived in New Orleans in 1833. He brought Parisian architectural styles that people in the city loved.

De Pouilly's first big cemetery project was for merchant Alexandre Grailhe. He designed a fancy Egyptian revival family tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, built in 1850. He designed many other tombs, mostly for wealthy people, in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. His designs were inspired by the famous Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

De Pouilly continued designing tombs for wealthy families and helpful organizations until he died in 1875. He used carved marble, granite, plaster, and cast-iron railings. These designs often had historical meaning or symbols.

Florville Foy, a free man of color, often built De Pouilly's tomb designs. He had a successful business as a marble cutter and sculptor for funerals.

Types of Tombs

From the late 1700s to the mid-1800s, most tombs were "box tombs" and "step tombs." These were brick structures with a flat roof, big enough for one coffin on the ground. Step tombs had stepped levels, allowing for more design.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, different "wall tombs" were built. These included oven tombs, wall vault tombs, and block vault tombs. They were single burial spaces built into walls around the cemetery edges or in free-standing buildings. These wall tombs usually had chambers stacked on top of each other, often four high. Sometimes, a new body could replace an older one in a chamber. Some of these were for groups or societies.

Family tombs and society tombs came in many styles. These included tombs with triangular tops (pediments), flat tops (parapets), or barrel-shaped roofs. Some even looked like sarcophagi. Styles included classical, Greek, Egyptian, Gothic, Romanesque, Renaissance, and Byzantine designs.

By the mid-1800s, large tombs with many vaults became common. These were bigger than family tombs and cheaper for individuals. mutual aid societies, fraternal organizations, and labor unions built these. Because of frequent epidemics like yellow fever and cholera, there was a high demand for more cemeteries and larger tombs. By the late 1800s, it cost about $100 USD to be buried in a society tomb. Over many years, hundreds of people could be buried in one society tomb.

Cemetery architects also found other ways to bury people above the high water table. "Coping graves" were common. Soil was built up above the ground and held in place by walls. This allowed for in-ground burials that were still above the water. Coping graves were most common in Jewish cemeteries, as Jewish tradition prefers in-ground burial.

Association Funerary Monuments

The Firemen's Benevolent Association started the Cypress Grove Cemetery. They later opened it to non-members. Other society tombs were built by groups like the Masons, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, and the Protective Order of Elks. Trade unions also built tombs. The New Orleans Typographical Union, the city's first labor union, built its tomb in Greenwood Cemetery in 1855.

The role of these helpful societies in funerals and cemeteries started to fade by the late 1800s. This was because government programs like the New Deal began to provide a safety net for people.

Ethnic Influences on Tombs

Many society tombs in the 1800s were built by different ethnic groups. The New Orleans Italian Mutual Benevolent Society had Italian artist Pietro Gualdi design its tomb in St. Louis Cemetery Number 1, finished in 1856. Gualdi's design used styles from the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods.

The Song On Tong Association built a tomb in Cypress Grove Cemetery in 1904. Its design fit the needs of the Chinese immigrant community it served. The cemetery faced east, towards the rising sun, which is important in Chinese architecture. The tomb had space inside for offerings like incense and food for the dead. This tomb was meant for temporary burial until the dead could be returned to China for permanent burial.

In the early 1900s, the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club was a group for African-Americans in New Orleans. It provided tombs for its members and their families.

Potter's Fields

Less wealthy people in New Orleans in the early 1800s were often buried in wall vaults in existing cemeteries. Their families paid rent for these spots. If the rent wasn't paid, the body would be removed. Locust Grove Cemetery No. 1 opened as a "potter's field" in 1859 for the poor. Locust Grove Cemetery No. 2 opened nearby in 1877. Both closed in 1879 and were later torn down. An elementary school and playground were built on their sites.

Later in the 1800s, Holt Cemetery was built as a potter's field for the very poor. Carrollton Cemetery and Charity Hospital Cemetery also had sections for indigent people. Burials at these places were usually shallow in-ground graves. A large number of African-American people were buried in these locations.

For much of New Orleans' history, even after the Jim Crow South, cemeteries remained segregated. African-Americans could be buried in established cemeteries, but only in specific sections set aside for them.

Rural Garden Cemeteries

In 1872, Metairie Cemetery opened on the edge of New Orleans. It was on higher ground. This was the first "rural garden cemetery" in the city. Even though it's called Metairie, it's actually inside New Orleans city limits. This cemetery doesn't show much French, Spanish, or Creole influence like the older ones. Many rich people are buried there, and their tombs have unique styles. It's known for having many celebrities and important historical figures. People sometimes called it "Suburbs of the Dead."

Other rural garden cemeteries followed Metairie Cemetery. One was Woodlawn Memorial Park Cemetery, opened in 1939. It was built on high ground and at first only had in-ground burials. But over time, families started building above-ground tombs there too, following New Orleans tradition.

Military Cemeteries

The Chalmette National Cemetery opened in New Orleans in 1864 during the American Civil War. It was created to honor soldiers who died in military conflicts. It was built where the Battle of New Orleans happened in the War of 1812. Its first purpose was to bury Union soldiers who died in Louisiana during the Civil War. About 7,000 deceased troops from other cemeteries were re-buried there. About 7,000 African-American civilians were also buried there. Soon after the Civil War, these civilians were re-buried at a new Freedmen's Cemetery next to Chalmette. Confederate troops buried there were also moved to other New Orleans cemeteries.

In 1874, Union Army veterans built the Grand Army of the Republic Monument at Chalmette National Cemetery. It honors soldiers who fought for the Union.

Military burials continued at Chalmette National Cemetery until the Vietnam War. In 2014, the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Cemetery took its place.

Cemeteries Today

Throughout the 1900s, the Historic Cemeteries of New Orleans became neglected and fell into disrepair. This was true even though many still accepted new burials. A newspaper article from 1906 said that some tombs were so broken you could see coffins inside.

Holt Cemetery, a potter's field, was especially neglected. Human remains were sometimes visible above ground, even though it was still actively used.

Why Cemeteries Deteriorated

Maintaining cemeteries in New Orleans has been hard. The soft, wet soil causes land to sink, and there are local floods. The hot, humid climate also damaged the above-ground tombs. People also caused damage through looting, vandalism, and purposeful destruction. Families who owned tombs sometimes didn't take care of them. When benevolent societies declined in the early 1900s, their tombs were neglected. Cemetery operators offered "perpetual care" plans to maintain tombs forever for a fee, but few people bought them, and sometimes the care wasn't done properly.

Restoration Efforts

An early effort to fix up the cemeteries started in 1923. The Society for the Preservation of Ancient Tombs, led by author Grace King, tried to restore tombs of famous people. They also found descendants to help with the work.

By the mid-1970s, the historic cemeteries were in very bad shape. A 1974 newspaper report called them "Slums of the Dead." The state health board said some tombs were a public health risk. Two cemeteries, Girod Street and Gates of Mercy, had even been torn down. Because of this, in 1974, the Louisiana State Legislature passed laws to stop the destruction of cemeteries.

Different groups started working to restore and preserve them. The most famous is Save Our Cemeteries. This group, led by Mary Louise Christovich, worked to make people aware of the cemeteries' condition. They raised money for restoration. They also helped get some New Orleans cemeteries listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, various companies and non-profit groups work to restore these historic cemeteries. The Archdiocese of New Orleans also has a plan to restore abandoned tombs in the Catholic cemeteries they manage.

In the early 2010s, the University of Pennsylvania studied some historic New Orleans cemeteries. They used mapping technology to assess their condition and risks.

Cemetery Management

Today, New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries, under the Archdiocese of New Orleans, owns and runs 13 of the historic cemeteries. The New Orleans Office of Property Management takes care of six others.

Hurricane Katrina Memorial

The Hurricane Katrina Memorial is a mausoleum (a building for tombs) that holds the remains of people who died in Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and were never identified. It is the newest cemetery with historic importance in New Orleans. It was finished and dedicated in 2008. The memorial is on land that was part of the Charity Hospital Cemetery.

After Hurricane Katrina, about 80 unidentified bodies were found. Local funeral directors and others in the funeral industry felt these people deserved a proper burial. They worked together to build this mausoleum. It has six small mausoleums around a central monument. The central monument looks like the eye of a hurricane. The walkways curve out from the center, like the hurricane's winds.

The memorial was dedicated on August 28, 2008, the third anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. The ceremony was cut short because Hurricane Gustav was threatening New Orleans that day.

Tomb of the Unknown Slave

The Tomb of the Unknown Slave is near St. Augustine Church in the Tremé Historic Neighborhood. It honors the many unmarked graves of enslaved people who died before the Civil War. Father Jerome LeDoux and church members built it. It was dedicated in 2004.

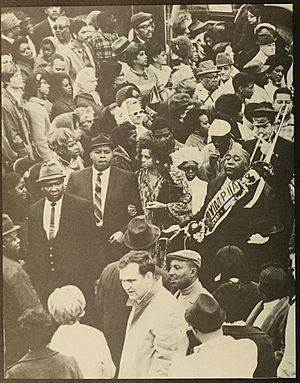

Jazz Funerals

Besides their architecture, New Orleans cemeteries are also known for their musical traditions. By 1868, the Masons included special performances in their funeral processions. All Saints' Day was also a lively event at New Orleans cemeteries in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

In the mid-1800s, benevolent societies in New Orleans started adding pageantry to the unveiling of their tombs. This came before the widespread practice of Jazz funerals. Jazz funerals began with African-American enslaved people in New Orleans. The tradition of sad songs followed by joyful music at funerals was seen in New Orleans as early as 1819. After slavery ended, brass bands became common at African-American funerals. With the rise of African-American benevolent associations, jazz funerals could be arranged for a fee. Today, they are often a big spectacle at New Orleans cemeteries.

Tourism in the Cemeteries

Since the early 1800s, New Orleans cemeteries have been gathering places for locals. Over time, stories grew about many historic cemeteries, like the one about voodoo queen Marie Laveau. These stories, along with Jazz funerals, have made the cemeteries popular with tourists. The cemeteries are architecturally unique, especially compared to others in the United States. As the city grew, the cemeteries became a clear part of its identity. The community's focus on them, their architecture, closeness, and stories all led to tourist interest.

The Louisiana Superdome is built near where the Girod Street Cemetery used to be. Some people jokingly say that the New Orleans Saints professional football team has had bad luck because their stadium was built on a historic cemetery.

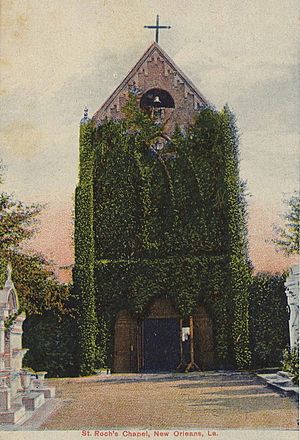

St. Roch Cemetery No. 1 has a chapel built in a Gothic style. It's called St. Michael's Chapel Mausoleum. The chapel is used for religious services and is open to visitors. It displays things like crutches, coins, and thank-you notes, which tourists find interesting.

A study found that 42% of visitors to New Orleans think the historic cemeteries are worth visiting. Several private tour companies offer organized tours, especially of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. This cemetery is only open to the public through these tours. The Archdiocese of New Orleans uses money from the tours to restore tombs. Many thousands of tourists visit these cemeteries each year.

The writer Mark Twain first called the historic cemeteries of New Orleans "Cities of the Dead." In his book "Life on the Mississippi," Twain wrote, "There is no architecture in New Orleans, except in the cemeteries." This phrase has become a popular saying for New Orleans tourism.

Several of these cemeteries are used as settings for TV shows, movies, and music videos. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in the Garden District is a popular choice.

List of Historic Cemeteries in New Orleans

This list shows the cemeteries in the order they were founded. "Extant" means they still exist.

| Name | Year established | Type | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Peter Street Cemetery | 1700s | Roman Catholic | Defunct | Closed in 1800 Archeologically significant |

| St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 | 1789 | Roman Catholic | Extant | In-ground burial at first Above ground tombs first appeared in 1804 |

| Girod Street Cemetery | 1822 | Protestant | Defunct | Closed in 1940, Bodies relocated Demolished in 1957 |

| St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 | 1823 | Roman Catholic | Extant | Many de Pouilly designed tombs |

| Gates of Mercy Cemetery | 1828 | Jewish | Defunct | Demolished in 1957 Remains moved to Hebrew Rest Cemetery |

| Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 | 1833 | Non-denominational | Extant | Located in the historic city of Lafayette Historically non-segregated |

| Cypress Grove Cemetery | 1840 | Benevolent associations | Extant | FIremen's Benevolent and Charitable Association Egyptian Revival main entrance |

| St. Patrick Cemeteries Nos. 1,2,3 | 1841 | Irish Catholic | Extant | Many in-ground burials in copings Undergoing restoration by Archdiocese of New Orleans |

| St. Vincent de Paul Cemeteries Nos. 1,2,3 | 1844 | Roman Catholic | Extant | Exact year of opening uncertain Contains some inappropriate historical restorations |

| Dispersed of Judah Cemetery | 1846 | Jewish | Extant | Land donated by Judah P. Touro Special section |

| Odd Fellows Rest Cemetery | 1847 | Benevolent associations | Extant | Not open to the public |

| Charity Hospital Cemetery | 1848 | Potter's field | Extant | Closed to new burials Contains memorial to victims of Hurricane Katrina |

| St. Bartholomew Cemetery | 1848 | Roman Catholic | Extant | West bank of New Orleans |

| Carrollton Cemetery | 1849 | Suburban | Extant | Many in-ground burials City of New Orleans Cemetery Department |

| Greenwood Cemetery | 1852 | Historic rural | Extant | Many benevolent associations have monuments there |

| St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 | 1854 | Roman Catholic | Extant | Elaborate crypts Greek Orthodox section |

| St. Joseph Cemetery No. 1 | 1854 | Roman Catholic | Extant | Sisters of Notre Dame for German immigrants Has a functioning chapel |

| Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 | 1858 | Benevolent associations | Extant | Most society tombs are abandoned Significant disrepair |

| Locust Grove Cemetery No. 1 | 1859 | Potter's field | Defunct | Locust Grove Cemetery No. 2 built nearby in 1877 Both closed in 1879 and subsequently demolished |

| Hebrew Rest Cemetery No. 1 | 1860 | Jewish | Extant | On the high ground of the Gentilly Ridge for above ground burial |

| St. Mary Cemetery | 1861 | originally Roman Catholic | Extant | West bank of New Orleans Acquired by the city of New Orleans in 1921, now non-denominational |

| Chalmette National Cemetery | 1864 | Military | Extant | Originally for Union soldiers that died in the US Civil War In-ground burials with gravestones |

| Gates of Prayer | 1864 | Jewish | Extant | Name changed from Temmeme Derech Cemetery in 1939 |

| Freedmen's Cemetery | 1867 | African-American | Defunct | Many deceased re-interred from the Chalmette National Battlefield Historical marker commemorates the location |

| Masonic Temple Cemetery | 1868 | Fraternal | Extant | Originally by Freemasons Burials not restricted to Freemasons |

| Metairie Cemetery | 1872 | Historic rural | Extant | Many contemporary notable and celebrity burials |

| St. Joseph Cemetery No. 2 | 1873 | Roman Catholic | Extant | Sisters of Notre Dame for German immigrants Has a functioning chapel |

| St. Roch Cemeteries Nos. 1 & 2 | 1874 | Roman Catholic | Extant | Originally for German immigrants Many victims of yellow fever epidemics |

| Holt Cemetery | 1879 | Potter's field | Extant | Below ground burials Unofficial burial ground before 1879 |

| Hebrew Rest Cemetery No. 2 | 1894 | Jewish | Extant | Expansion of Hebrew Rest Cemetery No. 1 |

| Ahavas Sholem Cemetery | 1897 | Jewish | Extant | Benevolent society by the same name For Eastern European Orthodox Jewish Immigrants |

| Mount Olivet Cemetery | 1920 | African-American | Extant | Above ground tombs and copings |

| Woodlawn Memorial Park Cemetery | 1939 | Historic rural | Extant | Above ground tombs with newer above ground tombs |

| Hurricane Katrina Memorial | 2008 | Mausoleum | Extant | Houses remains of unknown victims of Hurricane Katrina |

Gallery

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |