Historiography of the Gaspee affair facts for kids

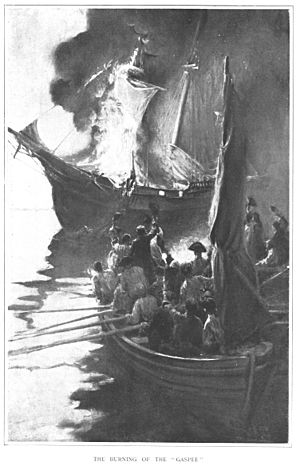

The historiography of the Gaspee affair is about how historians and experts have seen and written about the burning of HMS Gaspee. This was a British customs ship that got stuck near Newport, Rhode Island. Colonists attacked and destroyed it in 1772, leading up to the American Revolution.

Experts agree this event caused more tension between Great Britain and its colonies in North America. But they don't fully agree on how much it changed British and colonial policies and attitudes in the short or long term.

Contents

Early Reports on the Gaspee

In 1772, there were 38 newspapers in British America. At least 11 of them, mostly in the Northeast, reported the attack on the Gaspee soon after it happened.

The official investigation into the Gaspee incident was also a big topic. John Allen, a preacher in Boston, wrote an important pamphlet called An Oration, Upon the Beauties of Liberty, Or the Essential Rights of Americans. In December 1772, Allen gave a powerful sermon. It played on the colonists' fears and feelings.

Allen's Oration was printed seven times in four different cities. He argued that Britain and the American colonies were separate. He said one could not control the other. Allen told Lord Dartmouth that the colonists' actions were self-defense, not rebellion. This was an important point for his readers in early 1773. His Oration was one of the best-selling pamphlets of that time.

Later events, like the Boston Tea Party, quickly became more famous than the Gaspee incident. The strong reactions from the British Parliament in 1774 took over the news. Because of this, the Gaspee event has often been seen as a smaller part of the story leading up to the American Revolution. For example, when Richard Snowden wrote his history of the Revolution in 1796, he started with the Boston Tea Party. He did not mention the Gaspee.

Remembering the Gaspee in the 1800s

After 1800, writers began to create histories about the American Revolution. They also wrote about its famous people. Many made the Revolution seem like a "Golden Age." They played down its revolutionary side. This was partly because of upsetting revolutions in France, Haiti, and Latin America.

Other writers tried to interview older people who had lived through the Revolution. They even found some who had moved to Canada or London. Three colonists who were part of the Gaspee attack shared their memories. They were Dr. John Mawney, who treated the British lieutenant's wounds. Ephraim Bowen, who gave the gun to Joseph Bucklin. And Aaron Biggs, a servant who said he saw the events on June 9–10, 1772.

The colonial government and Patriot newspapers tried to say Biggs's story was not true. Biggs was kept on a British ship for his own safety. Bowen was only 19 in 1772. He later became a Colonel and ran a successful business. In 1839, at 86, Bowen tried to remember that night 67 years earlier. He believed everyone else involved was dead. So, he named as many people as he could recall.

Mawney's and Bowen's stories have a few small mistakes. But they are the only detailed eyewitness accounts from the colonial side. They said the men met at Sabin's Tavern. John Brown organized eight boats. Abraham Whipple told the Gaspee lookouts he was the Sheriff of Kent County. The Gaspee crew and officers gave many statements. But the Patriots of Rhode Island left very little information.

Historians Before the Civil War

For 40 years before the American Civil War, American historians wondered if their generation was as good as the founders. The country was dividing. People in the North and South argued over who truly understood the founders' dream. Leaders in Massachusetts wrote histories that showed New Englanders as the "true" founders of the whole country. They tried to define the nation's identity through their own regional worries.

During this time, the Gaspee found its main historian. In 1845, Rhode Island Judge William R. Staples published Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee. This is still the most detailed and well-known work on the Gaspee. It first appeared in the Providence Daily Journal. Later, it became a large pamphlet. Staples's work included 56 pages of letters from 1772-73.

Staples had studied law and became Chief Justice of Rhode Island's Supreme Court. He also helped start the Rhode Island Historical Society. His book has short notes where he shares his own views. But he mostly let the historical documents speak for themselves. When Staples did comment, he clearly supported the colonists. He saw their reasons as fair and the royal officials' reasons as bad.

Fifteen years after Staples, in 1860, Samuel G. Arnold wrote about the Gaspee in his History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He spent ten pages on the Gaspee's arrival, problems with Lieutenant Dudingston, the ship's destruction, and the investigation. Arnold wrote the Gaspee incident as a story in time order. He celebrated freedom winning over unfair rule. He called Lieutenant Dudingston's wounds "the first British blood shed in the war of independence."

Around the same time, from 1856 to 1865, John Russell Bartlett published a ten-volume set of Rhode Island's colonial records. In 1862, volume 7 came out. It covered 1770–1776. This volume included 136 pages on the Gaspee affair. It also had some extra letters not found in Staples's work. Bartlett had published almost the same pages a year earlier as a separate book. It was called A History of the Destruction of His Britannic Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, in Narragansett Bay, on the 10th June, 1772. Bartlett's book was similar to Staples's. But Bartlett added more thoughts and comments in the footnotes.

Bartlett said he released his book because Staples's work was hard to find. Both Staples and Bartlett were important Rhode Islanders. They shared a common view of the American Revolution. They felt they had covered the topic well for their time. After their books, no other full-length book for adults about the Gaspee was published for a long time. Their work showed the more positive and sure attitude of the early 1800s.

The Imperial School of Thought

From 1865 to 1900, not many historians wrote about Rhode Island events leading to the American Revolution. Instead, much energy went into writing about the causes of the Civil War. They also wrote detailed stories of every battle. Many of these histories did not connect to bigger changes of the 1800s.

Meanwhile, more professional historians began to visit British archives. They wanted to find out what information officials in London had. They also wanted to know how London made decisions about the American colonies. This way of thinking became known as the "Imperial School." It gave a more balanced view of the conflict. It looked at the reasons for both the Patriots and Loyalists. It also looked at the reasons for the British Parliament.

Historians like George Louis Beer and Herbert L. Osgood studied changes in how people thought about trade. These ideas influenced the decisions of the Privy Council when dealing with the American colonies. After the Seven Years' War, Britain gave back some colonies to France. But they kept Canada. This changed how colonies were managed. New markets became more important than just producing resources. Controlling and collecting money from colonial markets became a major source of disagreement in the 1760s and 1770s.

Images for kids