History of Jerusalem during the Early Muslim period facts for kids

The history of Jerusalem during the Early Muslim period covers a time when the city was taken over by Arab Muslim armies. This happened around 637–638 CE, when they captured it from the Byzantine Empire. This period ended in 1099, when European Christian armies from the First Crusade conquered the city. During these centuries, Jerusalem was mostly a Christian city, but it also had smaller Muslim and Jewish communities. It was ruled by several different Muslim states, including the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates. These groups often fought over the city with other powers like the Seljuks, until the Crusaders finally took control.

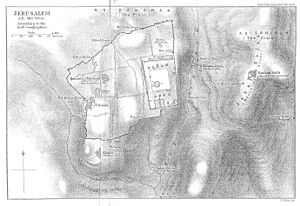

The second caliph, Umar (who ruled from 634 to 644), made sure Muslims controlled Jerusalem. During his rule, Muslims likely started praying on the Temple Mount. Also, a small number of Jewish people were allowed to live in the city again, after being banned for hundreds of years by the Romans and Byzantines. Later, the Umayyad caliphs, starting with Mu'awiya I (who ruled from 661 to 680), paid special attention to Jerusalem because it was a holy city. Many leaders even took their oaths of loyalty there. Caliphs Abd al-Malik (685–705) and al-Walid I (705–715) spent a lot of money building important Muslim structures on the Temple Mount, like the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque. They also built other religious and administrative buildings, gates, and roads. Their successor, Sulayman (715–717), probably lived in Jerusalem at the start of his rule. However, when he founded the nearby city of Ramla, it eventually caused Jerusalem to lose some of its political and economic importance.

Contents

Jerusalem's Early Muslim History: An Overview

Throughout the early Muslim period and during the Crusades, Jerusalem had a large Christian population. This only changed in 1187 when Saladin conquered the city and removed many of the Frankish (European Christian) residents.

In the first few centuries of Muslim rule, especially under the Umayyad (661–750) and Abbasid (750–969) dynasties, Jerusalem thrived. Geographers from the 10th century, like Ibn Hawqal and al-Istakhri, described it as "the most fertile province of Palestine." A famous geographer born in Jerusalem, al-Muqaddasi (born 946), wrote many pages praising the city in his well-known book. However, Jerusalem under Muslim rule never became as politically or culturally important as major capitals like Damascus, Baghdad, or Cairo.

After the decline of the Carolingian Empire in 888, Muslims began to persecute Christians more. But the Byzantine Empire grew stronger and expanded. As a result, Christians were once again allowed to make pilgrimages to Jerusalem.

Rashidun Period (630s–661): How Jerusalem Became Muslim

Conquering the Countryside

Muslims, led by commander Amr ibn al-As, conquered southern Palestine after a big victory over the Byzantines at the Battle of Ajnadayn in 634. This battle likely happened about 25 kilometers (15 miles) southwest of Jerusalem. Even though Jerusalem itself wasn't occupied yet, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Sophronius, mentioned in his Christmas sermon of 634 that Arab Muslims controlled the areas around the city. He couldn't even travel to nearby Bethlehem for the Christmas celebration because of Arab raiders.

Some historical accounts suggest that a Muslim advance force was sent towards Jerusalem by Amr ibn al-As on his way to Ajnadayn. By 635, southern Syria was under Muslim control, except for Jerusalem and Caesarea, the Byzantine capital of Palestine. In a sermon around 636–637, Sophronius sadly spoke about the killings, raids, and destruction of churches by the Arabs.

Siege and Surrender of Jerusalem

It's not exactly clear when Jerusalem was captured, but most historians believe it was in the spring of 637. In that year, the troops of Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, the main commander of Muslim forces in Syria, surrounded the city. Historical records show that Caliph Umar (634–644), who was based in Medina, visited Jabiya, the main Muslim camp in Syria, in 637–638. Modern historians like Fred Donner and Hugh N. Kennedy think he came to deal with many administrative issues in the newly conquered region. While in Jabiya, Umar negotiated Jerusalem's surrender with a group from the city. The Patriarch insisted on surrendering directly to the Caliph, not his commanders.

The earliest known Muslim story about Jerusalem's capture comes from the historian al-Baladhuri (died 892). It says that the Arab commander Khalid ibn Thabit al-Fahmi arranged the city's surrender. The terms guaranteed Muslim control of the countryside and protected the city's people in exchange for tribute payments. Khalid ibn Thabit had been sent by Umar from Jabiya. Historian Shelomo Dov Goitein believes this is the most reliable account of Jerusalem's capture.

Another account, found in the histories of al-Ya'qubi (died 898) and Eutychius of Alexandria (died 940), says that a treaty was agreed upon between the Muslims and Jerusalem's residents. The terms were mostly the same as those mentioned by al-Baladhuri. The 10th-century history by al-Tabari, quoting the 8th-century historian Sayf ibn Umar, gives a detailed version of the surrender agreement. However, parts of it might have been changed over time.

The agreement for Jerusalem was generally good for the city's Christian residents. It guaranteed the safety of their lives, property, and churches. It also allowed them freedom of worship in exchange for paying the jizya, which was a tax. Byzantine troops and other residents who wanted to leave the city were promised safety from the time they left Jerusalem until they reached their departure point from Palestine. Historian Moshe Gil believes Umar took a gentle approach so that the residents could continue their lives and work. This way, they could help support the Arab tribes stationed in Palestine.

The treaty mentioned in al-Tabari and later Christian sources included a rule that Jewish people could not live alongside Christians in the city. This continued a ban that had started during the time of Emperor Hadrian (117–138) and was renewed by Emperor Constantine (306–337). Among these sources was the history by Michael the Syrian (died 1199), who wrote that Sophronius negotiated this ban on Jews living in Jerusalem.

Several later Muslim and Christian accounts, as well as an 11th-century Jewish chronicle, mention a visit to Jerusalem by Umar. Some accounts say that Umar was guided by Jewish people who showed him the Temple Mount. In Muslim and Jewish stories, a famous Jewish convert to Islam, Ka'b al-Ahbar, suggested that Umar pray behind the Foundation Stone. This way, both qiblas (the direction points for Islamic prayer) would be behind him. Umar refused, saying that the Ka'aba in Mecca was the only qibla. Jerusalem had been the first qibla for early Muslims until Muhammad changed it to the Ka'aba. Muslim and Jewish sources reported that the Temple Mount was cleaned by the Muslims of the city and its area, along with a group of Jewish people. The Jewish account also noted that Umar oversaw the cleaning and talked with Jewish elders. Gil suggests these elders might refer to Ka'b al-Ahbar. Christian accounts mentioned that Umar visited Jerusalem's churches but refused to pray in them. He did this to avoid setting a rule for future Muslims to pray in Christian holy places. This story might have been created by later Christian writers to support efforts against Muslims taking over their holy sites.

Life in Jerusalem After the Conquest

Historians Goitein and Amikam Elad believe Jerusalem was the main Muslim political and religious center in the district of Palestine from the conquest until the city of Ramla was founded in the early 8th century. Before that, the main Muslim military camp might have been at Emmaus Nicopolis, but it was abandoned due to the Plague of Amwas in 639. Historian Nimrod Luz, however, thinks that early Muslim traditions show Palestine had two capitals from Umar's time: Jerusalem and Lydda. Each city had its own governor and soldiers. A group of soldiers from Yemen was stationed in Jerusalem during this time. Amr ibn al-As started the conquest of Egypt from Jerusalem around 640. His son, Abd Allah, shared stories (hadiths) about the city.

Christian leadership in Jerusalem became disorganized after Sophronius died around 638. No new patriarch was appointed until 702. Still, Jerusalem remained mostly Christian during the early Islamic period. Not long after the conquest, possibly in 641, Umar allowed a limited number of Jewish people to live in Jerusalem after talking with the city's Christian leaders. An 11th-century Jewish record found in the Cairo Geniza indicates that Jewish people asked to settle two hundred families. The Christians only agreed to fifty, and Umar finally decided on seventy families from Tiberias. Gil believes the Caliph made this decision because he recognized the importance of Jewish people locally, due to their large presence and economic strength in Palestine. He also wanted to reduce Christian dominance in Jerusalem.

At the time of the conquest, the Temple Mount was in ruins. Byzantine Christians had largely left it unused for religious reasons. Muslims took over the site for administrative and religious purposes. This was likely for several reasons. The Temple Mount was a large, empty space in Jerusalem. Muslims were not allowed to take Christian-owned property in the city because of the surrender terms. Jewish converts to Islam might have also told early Muslims about the site's holiness. Early Muslims might have also wanted to show they disagreed with the Christian belief that the Temple Mount should remain empty. Also, early Muslims might have felt a spiritual connection to the site before the conquest. Using the Temple Mount gave Muslims a huge space overlooking the entire city. The Temple Mount was probably used for Muslim prayer from the beginning of Muslim rule, because the surrender agreement stopped Muslims from using Christian buildings. Umar might have approved this use of the Temple Mount. Stories from 11th-century Jerusalemites al-Wasiti and Ibn al-Murajja say that Jewish people were hired to take care of and clean the Temple Mount. Those who worked there were excused from paying the jizya tax.

The first Muslim settlements were built south and southwest of the Temple Mount, in areas that were not very populated. Most Christian settlements were in western Jerusalem, around Golgotha and Mount Zion. The first Muslim settlers in Jerusalem mainly came from the Ansar, who were people from Medina. They included Shaddad ibn Aws, who was the nephew of a famous companion of Muhammad and a poet named Hassan ibn Thabit. Shaddad died and was buried in Jerusalem between 662 and 679. His family remained important there, and his tomb later became a place people visited to show respect. Another important companion, the Ansarite commander Ubada ibn al-Samit, also settled in Jerusalem. He became the city's first qadi (Islamic judge). The father of Muhammad's Jewish concubine Rayhana and a Jewish convert from Medina, Sham'un (Simon), settled in Jerusalem. According to Mujir al-Din, he gave Muslim sermons on the Temple Mount. Umm al-Darda, an Ansarite woman and the wife of the first qadi of Damascus, lived in Jerusalem for half of the year. Umar's successor, Caliph Uthman (644–656), was said by the 10th-century Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi to have set aside the money from the rich vegetable gardens of Silwan, on the city's outskirts, for the city's poor. These gardens would have been Muslim property according to the surrender terms.

Umayyad Period (661–750): Building Jerusalem's Identity

Sufyanid Period (661–684)

Caliph Mu'awiya I (661–680), who founded the Umayyad Caliphate, first served as governor of Syria under Umar and Uthman. He opposed Uthman's successor Ali during the First Muslim Civil War. In 658, he made an agreement against Ali with Amr ibn al-As, the former governor of Egypt and conqueror of Palestine, in Jerusalem.

According to the Maronite Chronicle and Islamic traditional accounts, Mu'awiya received oaths of loyalty as caliph in Jerusalem at least twice between 660 and July 661. Although the exact dates are not consistent, Muslim and non-Muslim accounts generally agree that the oaths to Mu'awiya happened at a mosque on the Temple Mount. This mosque might have been built by Umar and expanded by Mu'awiya, though there are no clear remains of the structure today. The Maronite Chronicle notes that "many emirs and Tayyaye [Arab nomads] gathered [at Jerusalem] and offered their right hand[s] to Mu'awiya." Afterward, he sat and prayed at Golgotha and then prayed at Mary's Tomb in Gethsemane. The "Arab nomads" were likely the local Arab tribesmen of Syria. Most of them had converted to Christianity under the Byzantines, and many had kept their Christian faith during the early decades of Islamic rule. Mu'awiya's prayer at Christian sites showed respect for the Syrian Arabs, who were the basis of his power. His advisers Sarjun ibn Mansur and Ubayd Allah ibn Aws the Ghassanid might have helped organize the ceremonies in Jerusalem.

Mu'awiya's son and successor, Yazid I (680–683), might have visited Jerusalem several times during his life. Historian Irfan Shahid suggests that these visits, with the famous Arab Christian poet al-Akhtal, were attempts to strengthen his claim as caliph among Muslims.

Marwanid Period (684–750)

The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (685–705), who had been governor of Palestine under his father Caliph Marwan I (684–685), also received his oaths of loyalty in Jerusalem. From the start of his rule, Abd al-Malik planned to build the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, both on the Temple Mount. The Dome of the Rock was finished in 691–692, becoming the first major example of Islamic architecture. Its construction was overseen by the Caliph's religious adviser Raja ibn Haywa and his Jerusalemite helper Yazid ibn Salam. The building of the Dome of the Chain on the Temple Mount is also generally credited to Abd al-Malik.

Abd al-Malik and his powerful governor over Iraq, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, are credited in Islamic tradition with building two gates of the Temple Mount. Historian Amikam Elad suggests these are the Prophet's Gate and the Mercy Gate, which modern scholars also believe were built by the Umayyads. The Caliph repaired the roads connecting his capital Damascus with Palestine and linking Jerusalem to its eastern and western areas. Evidence of these roadworks comes from seven milestones found in the region. The oldest dates to May 692 and the latest to September 704. These milestones, all with inscriptions crediting Abd al-Malik, were found in or near Fiq, Samakh, St. George's Monastery of Wadi Qelt, Khan al-Hathrura, Bab al-Wad, and Abu Ghosh. A piece of an eighth milestone, likely made soon after Abd al-Malik's death, was found at Ein Hemed, just west of Abu Ghosh. This road project was part of the Caliph's effort to centralize his power. Palestine received special attention because it was a key travel area between Syria and Egypt, and Jerusalem was religiously important to the Caliph.

Many buildings were constructed on the Temple Mount and outside its walls under Abd al-Malik's son and successor al-Walid I (705–715). Modern historians generally credit al-Walid with building the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount. However, the mosque might have been started by earlier Umayyad rulers; even so, al-Walid was still responsible for a large part of its construction. Ancient papyrus documents from Aphrodito show that workers from Egypt were sent to Jerusalem for six months to a year to work on the al-Aqsa Mosque, al-Walid's caliphal palace, and a third, unnamed building for the Caliph. Elad believes that the six Umayyad buildings found south and west of the Temple Mount might include the palace and the unnamed building mentioned in the papyri.

Al-Walid's brother and successor Sulayman (715–717), who had been governor of Palestine under al-Walid and Abd al-Malik, was first recognized as caliph in Jerusalem by Arab tribes and important people. He lived in Jerusalem for some time during his rule. His contemporary, the poet al-Farazdaq, may have hinted at this in a verse: "In the Mosque al-Aqsa resides the Imam [Sulayman]." He built a bathhouse there, but he might not have loved Jerusalem as much as his predecessors. Sulayman's building of a new city, Ramla, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) northwest of Jerusalem, eventually caused Jerusalem to lose its importance. Ramla became the administrative and economic capital of Palestine.

According to the Byzantine historian Theophanes the Confessor (died 818), Jerusalem's walls were destroyed by the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, in 745. At that time, the Caliph had put down Arab tribes in Palestine who had joined a revolt against him in northern Syria.

Muslim Pilgrimage and Traditions in the Umayyad Period

Under the Umayyads, Muslim religious ceremonies and pilgrimages in Jerusalem focused on the Temple Mount. To a lesser extent, they also visited the Prayer Niche of David (possibly the Tower of David), the Spring of Silwan, the Garden of Gethsemane and Mary's Tomb, and the Mount of Olives. The Umayyads encouraged Muslim pilgrimage and prayer in Jerusalem. Traditions that started during the Umayyad period praised the city. During this time, Muslim pilgrims came to Jerusalem to prepare themselves before making the Umra or Hajj pilgrimages to Mecca. Muslims who could not make the pilgrimage, and possibly Christians and Jews, donated olive oil to light up the al-Aqsa Mosque. Most Muslim pilgrims to Jerusalem were probably from Palestine and Syria, but some came from far away parts of the Caliphate.

Abbasids, Tulunids, and Ikhshidids (750–969): Changing Rulers

The Umayyads were overthrown in 750 by the Abbasid dynasty. The Abbasids then ruled the Caliphate, including Jerusalem, with some breaks, for the next two centuries. This period is not as well documented as others. Any building activity was mainly focused on repairing structures on the Temple Mount that were damaged by earthquakes. Caliphs al-Mansur (754–775) and al-Mahdi (775–785) ordered major rebuilding of the al-Aqsa Mosque after earthquake damage.

After the first Abbasid period (750–878), the Tulunids, a dynasty of Turkic origin, ruled Egypt and much of Greater Syria, including Palestine, for almost three decades (878–905). Ahmad ibn Tulun, who founded this Egypt-based dynasty, took control of Palestine between 878 and 880. His son inherited it after his death in 884. According to Patriarch Elias III of Jerusalem, Ibn Tulun ended a period of persecution against Christians by naming a Christian governor in Ramla (or perhaps Jerusalem). This governor started renovating churches in the city. Ibn Tulun had a Jewish doctor and was generally very tolerant towards dhimmis (non-Muslims living under Muslim rule). When he was dying, both Jewish and Christian people prayed for him. Ibn Tulun was the first in a line of Egypt-based rulers of Palestine, which ended with the Ikhshidids. While the Tulunids kept a lot of independence, the Abbasids took back control over Jerusalem in 905. Between 935 and 969, it was managed by their Egyptian governors, the Ikhshidids. During this entire time, Jerusalem's religious importance grew, and several Egyptian rulers chose to be buried there.

Abbasid rule returned between 905 and 969. The first 30 years were direct rule from Baghdad (905–935), and the rest was through the Ikhshidid governors of Egypt (935–969). The mother of Caliph al-Muqtadir (908–932) had wooden porches built under all the city gates and repaired the Dome of the Rock.

The Ikhshidid period saw acts of persecution against Christians. This included an attack by Muslims on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in 937, where the church was set on fire and its treasures stolen. These tensions were linked to the growing threat from the Byzantine Empire. Because of this, Jewish people joined forces with Muslims. In 966, a Muslim and Jewish crowd, encouraged by the Ikhshidid governor, attacked the Church of the Holy Sepulchre again. The resulting fire caused the dome over Jesus's Tomb to collapse and led to the death of Patriarch John VII.

Fatimids and Seljuks (970–1099): A Time of Change and Conflict

The start of the first Fatimid period (970–1071) saw a mostly Berber army conquer the region. After sixty years of war and another forty years of relative peace, Turkish tribes invaded the region. This began a period of constant unrest, with groups fighting each other and the Fatimids. In less than thirty years of warfare and destruction, much of Palestine was ruined, causing terrible hardship, especially for the Jewish population. However, Jewish communities stayed in their places, only to be forced out after 1099 by the Crusaders. Turkish rule meant more than a quarter-century of continuous warfare. This negatively affected the local Christian communities and eventually blocked access for pilgrims from Europe. This situation is seen as a factor that helped start the Crusades. We also know about a visitor from Muslim Spain who wrote a report about the busy activity in Jerusalem's Sunni schools and his interactions with Jewish and Christian people in the years 1093–95.

Between 1071 and 1076, Turkman tribes captured Palestine, with Jerusalem falling in 1073. These Turcomans acted independently in the region but became known as Seljuks because they were associated with the main Turkish rulers who invaded the Arab Muslim lands, the Seljuk dynasty. Seljuk emir Atsiz ibn Uvaq, leader of the Turkic Nawaki tribe, surrounded and captured Jerusalem in 1073 and held it for four years. Atsiz placed the land he captured under the nominal control of the Abbasid caliphate. In 1077, after a failed attempt to capture Cairo, the capital of the Fatimid caliphate, he found that the people of Jerusalem had rebelled in his absence. They had forced his soldiers to hide in the citadel and captured the families and property of the Turcomans. Atsiz then besieged Jerusalem and promised the defenders aman (pardon and safety) if they surrendered. They did, but Atsiz broke his promise and killed 3,000 residents, including those who had taken shelter in the Al-Aqsa Mosque. He only spared those inside the Dome of the Rock. In 1079, Atsiz was murdered by his ally Tutush, who then established stronger Abbasid control in the area. After Atsiz, other Seljuk commanders ruled Jerusalem and used it as a base for their ongoing wars. A new period of trouble began in 1091 with the death of Tutush's governor in Jerusalem, Artuq, and the succession of his two sons, who were bitter rivals. The city changed hands between them several times until August 1098. At that point, the Fatimids, seeing an opportunity because the First Crusade was approaching, regained control of the city and ruled it for less than a year.

Jewish Community in the 11th Century

The Jewish population suffered greatly during the difficult years of Turkish rule. Even the Jerusalem yeshiva, which was the main center for Jewish law in Palestine, had to move to Tyre sometime after 1078, following the rebellion against Atsiz. However, there is no information on whether Jewish people took part in that rebellion alongside Muslim citizens.

According to Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, German Jews lived in Jerusalem during the 11th century. There's a story that a German-speaking Jewish person from Palestine saved the life of a young German man named Dolberger. So, when the knights of the First Crusade came to besiege Jerusalem, one of Dolberger's family members, who was among them, rescued Jewish people in Palestine and took them back to Worms to repay the favor. More evidence of German Jewish communities in the holy city comes from religious questions sent from Germany to Jerusalem during the second half of the 11th century.

Christian Community in the 11th Century

As the Byzantine borders expanded into the Levant in the early 11th century, the limited tolerance of Muslim rulers toward Christians in the Middle East began to decrease. The Egyptian Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of all churches throughout the Muslim world, starting with those in Jerusalem. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which all Christians at the time revered as the site of Jesus's crucifixion and burial, was among the places of worship destroyed. However, permission was later given for it to be rebuilt.

The suffering and hardship caused by decades of aggressive Turkish rule led some local Christians to expect the End of Days to be near. Also, because of the constant warfare, the ports of Palestine, mostly controlled by the Fatimids, turned away pilgrim ships arriving from Europe in 1093. This situation contributed to the start of the First Crusade. Overall, although information is very limited, it seems that the Turcomans favored the Jacobites and Latins over the Greek Orthodox Christians. The Greek Orthodox were seen as being too close to the Byzantine Empire, which was a constant enemy.

See also

- Islamization of Jerusalem