History of New Plymouth facts for kids

The city of New Plymouth in New Zealand has a rich history. It was home to Māori for a long time. Later, European traders and settlers arrived in the 1800s. This led to conflicts and wars because the two cultures had different ideas, especially about land.

European settlement started in the early 1840s. Many Māori people were not in the area then. Some had been captured by northern Māori warriors. Others had moved south to avoid wars. As more European settlers arrived, they needed more land. The New Zealand Company bought land in ways that caused problems with local Māori. This led to a war in the 1860s. New Plymouth became a fortified town during this time. Its people faced hunger and sickness. Farming stopped, and new people stopped arriving. Trade also slowed down.

After the war, New Plymouth grew quickly. Better roads and rail links helped connect it to other towns. The town became a major port for sending out dairy products from the Taranaki region. It also became the main centre for Taranaki's oil and gas industry.

Contents

Early Days: Māori Life and First European Contact

For many centuries, the area where New Plymouth now stands was home to several Māori iwi (tribes). Around 1823, Māori started meeting European whalers and traders. These traders arrived by schooner (a type of sailing ship) to buy flax.

In March 1828, a trader named Richard "Dicky" Barrett set up a trading post at Ngamotu. He arrived on a ship called Adventure. The Te Āti Awa tribe welcomed Barrett and his friends. They hoped the Europeans, with their muskets and cannons, would help them in their wars with the Waikato Māori. The Europeans also brought cloth, food, and tools.

After a battle at Ngamotu in 1832, most of the 2,000 Āti Awa people living nearby moved south. They went to the Kāpiti region and Marlborough. About 300 stayed behind. They lived on the newly fortified Moturoa and Mikotahi, which are two of the Sugar Loaf Islands west of Ngamotu. Barrett also left the area for a while. The Waikato Māori returned in 1833. They surrounded the remaining Āti Awa until they surrendered almost a year later.

How New Zealand Company Bought Land (1838–1840)

In 1838, the New Zealand Company was created in England. Its goal was to help people move from crowded English cities to New Zealand. They planned to sell land to settlers who would become farmers and workers. A separate group, the Plymouth Company, started in Plymouth in February 1840. It was managed by Thomas Woolcombe. Many streets in New Plymouth are named after the company's leaders. The Plymouth Company joined the New Zealand Company in April 1841 after losing money.

Barrett returned to Ngamotu in November 1839 on the ship Tory. This ship was exploring for the New Zealand Company. With him was Colonel William Wakefield, who bought land for the company. A month earlier, Wakefield claimed to have bought a huge area of New Zealand (about one-third of the country) from some Taranaki and other Māori in Wellington.

Barrett could speak some Māori. He was the only person working for the New Zealand Company to buy land in Taranaki. On February 15, 1840, a formal Deed of Sale was signed by 75 Māori individuals. This was the same month the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. Payment was made with guns, blankets, and other goods. Many people later said that Barrett did not read the deed or explain it well when it was signed. The purchases included a large area in central Taranaki, from Mokau to Cape Egmont, and inland to the Whanganui River, including Mt Taranaki. A second deed, called the Nga Motu deed, included New Plymouth and all the coastal lands of North Taranaki, including Waitara. The company had already started selling this land to settlers in England, expecting to own it legally.

J. Houston wrote in Maori Life in Old Taranaki (1965) that many true owners of the land were not there. Others had not returned from being captives of the Waikato Māori. So, the 72 chiefs of Ngamotu "cheerfully sold lands in which they themselves had no interest." They also sold lands where they only owned a small part with others. Māori did not fully understand the sale. This confusion later led to tension and war over land. Barrett's translation skills were not good. At later hearings, he was asked to translate a long legal document. He reportedly turned a 1,600-word English document into 115 "meaningless Maori ones."

The Waitangi Tribunal noted that Wakefield's purchase was not valid. On January 14, 1840, George Gipps, the Governor of New South Wales (which New Zealand was part of), said that any Māori land bought by private groups after that date would not be legal. In November, the company gave up its large "purchases." Instead, it got four acres (1.6 hectares) for every pound it had spent on settling the land.

Choosing the Site for New Plymouth (1841)

Eleven months later, on December 12, 1840, Frederic Alonzo Carrington arrived in Wellington. He was the 32-year-old Chief Surveyor for the Plymouth Company. His job was to create a 44 square kilometre (11,000 acre) settlement in New Zealand for people from the West Country of England. Wakefield had already been told that the Plymouth Company would take over some of the New Zealand Company land. He urged Carrington to choose a site at Ngamotu.

Carrington was under a lot of pressure. The first ship of settlers had already left Plymouth on November 19 and was on its way to New Zealand. Carrington asked Barrett to join his team. Around January 9, 1841, they arrived at Ngamotu with other surveyors on a ship called Brougham. They were ready to choose a site for the new town.

Carrington looked at the area around Moturoa. Then he took a whaleboat to explore Waitara, rowing 5 kilometres up the Waitara River. He returned to Wellington, wanting to check sites in the South Island before deciding. Barrett guided the Brougham around empty areas near Nelson. He pointed out swampy places that would not be good for settlement. Some believe Barrett did this on purpose. He wanted to make sure Carrington chose Taranaki instead of Nelson. On January 26, Carrington told Wakefield that he had chosen Ngamotu, despite his concerns.

He wrote to Woolcombe in Plymouth: "I have chosen a place where small harbours can be easily made. There is plenty of material right here. I have placed the town between the Huatoki and Henui rivers. Two or three streams run through the town, and water is available everywhere. The soil, I think, cannot be better. There is much open or fern country and plenty of good timber."

Carrington told Woolcombe he had thought about putting the town at the Waitara River. He had explored it twice and found beautiful land. "I once decided to have the town there," he wrote. "But the almost constant surf on the river bar made me prefer this place. The New Plymouth Company has the garden of this country; all we need is workers and especially working oxen."

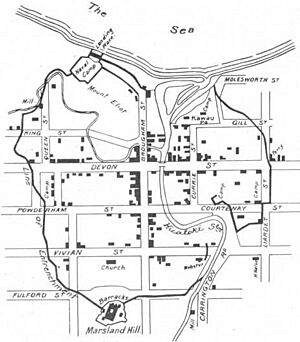

New Plymouth was planned over 550 acres (2.2 square kilometres). More rural sections were planned along the coast beyond Waitara, covering 68,500 acres (274 square kilometres). By the end of the year, Carrington's map showed 2,267 sections ready for settlers. It included streets, squares, hospitals, schools, and parks. These were surrounded by wide roads that separated the town from the suburbs. For many years, settlers criticized Carrington. They thought New Plymouth was poorly chosen because it did not have a natural harbour.

The First Settlers Arrive (1841)

The first settlers arrived on the ship William Bryan. It anchored off the coast on March 31, 1841. There were 21 married couples, 22 single adults, and 70 children on board. George Cutfield, the leader of the group, wrote home. He described the settlement as "a fine country with a lot of flat land. But every part is covered with plants, fern, scrub, and forest. The fern, on good land, is usually four to six feet high. There are thousands of acres of this land that will need only a small effort to farm."

Temporary homes were set up on Mount Eliot (where the Puke Ariki museum is today). Settlers became frustrated. They had to live in homes made of rushes and sedges through the winter. There were many rats, food supplies were running low, and people worried about another attack by Waikato Māori. The first suburban sections were not ready until October. Those who bought town sections had to wait until mid-November.

The second ship, Amelia Thompson, arrived off the Taranaki coast on September 3. It stayed offshore for five weeks. Its captain thought Ngamotu was a dangerous place for ships. Barrett and his men helped its 187 passengers get ashore over two weeks. Each small boat trip from the ship to the shore took five hours. The ship's important food cargo, including flour and salted meat, finally reached New Plymouth's hungry residents on September 30. The loss of its baggage ship, the Regina, which was blown onto a reef, made New Plymouth seem even more dangerous for shipping. This discouraged other ships from coming.

One account said settlers were "complaining loudly about ever leaving England." Life was a constant struggle to protect themselves from the weather. They also had to protect their food from termites, insects, and hungry animals. Many workers drank too much because life was boring and there was not enough to do. Flour supplies ran out again, and no more were expected until the next ship of settlers arrived. The Te Āti Awa people were also hungry. The ones who cooperated had planted more crops than usual to feed the arriving Europeans. But so many more Europeans arrived than expected, that they also ran short of food.

As summer came, buildings were put up, gardens were planted, and wheat was sown. Other ships soon arrived, bringing more workers and food. These included the Oriental (130 passengers) on November 7, 1841; the Timandra (202 passengers) on February 23, 1842; the Blenheim (138 passengers) on November 19, 1842; and the Essex (115 passengers) on January 25, 1843. By this time, the town was a collection of huts made of raupo (a type of reed) and timber, housing almost 1,000 Europeans.

Land Disputes and Growing Tensions (1842–1866)

As settlers arrived, they took over land sections along the coast, even beyond Waitara. Many had bought land from the New Zealand Company before the company actually owned it. Soon, tensions grew between Māori and settlers. In July 1842, a group of settlers were forced off land north of the Waitara River. In 1843, a group of 100 Māori stopped surveyors. Despite this, the town continued to grow. By 1844, it had two flour mills on the Huatoki River. By 1847, about 841 hectares of land were being farmed.

In May 1844, William Spain, a Land Claims Commissioner, began looking into the New Zealand Company's land claims in Taranaki. The company withdrew its two large land claims from 1840. It only claimed the Nga Motu area as "legally purchased." Spain agreed with the company. He approved its claim to 24,000 hectares north of the Sugar Loaf Islands. However, he excluded Māori villages (pas), burial places, and cultivated land (48 hectares). He also set aside 10 percent of the land (2,400 hectares) for Māori reserves, 40 hectares for the Wesleyan Mission Station, and 72 hectares for Barrett and his family.

On July 2, Spain wrote to Governor Robert FitzRoy. He suggested using military force to convince Māori that this was for their own good. He wanted to show "our power to enforce obedience to the laws, and of the utter hopelessness of any attempt on their part at resistance." Spain believed New Zealand was settled for good reasons, "to benefit the Natives by teaching them the usefulness of habits of industry, and the advantages attendant upon civilisation."

J.S. Tullett, in his history of the city, wrote that Māori "received the award with great hostility." They sent strong protest letters to FitzRoy, who was sympathetic. After visiting New Plymouth in late 1844, FitzRoy officially cancelled Spain's award. He admitted the land had been sold without the agreement of those Māori who were absent. He replaced it with a 1,400-hectare block. This became known as the "Fitzroy block." It included the town site and only the immediate surrounding area. Many settlers who had taken land outside this block had to move back inside its borders. This made them very angry at FitzRoy.

According to the Waitangi Tribunal, the Fitzroy block deal was more like a "political agreement." It was based on the fact that settlers were already on the land. They had to be either accepted or forced out. The sale was "more like a treaty." Māori also set two important conditions. First, settlers still outside the Fitzroy block would be brought back into it. Second, the settlers would not expand any further. A 12-metre high boundary marker, called the FitzRoy Pole, was later put up on the banks of the Waiwakaiho River. It showed the limit of Pākehā (European) settlement.

However, more migrants kept arriving. In 1847, FitzRoy's successor, George Grey, responded to settler anger. He pressured Te Āti Awa leaders to sell more land. When they refused, he turned to individual Māori who were willing to accept payment. Through these secret deals, Grey bought 10,800 hectares in five areas. Two were at Tataraimaka and Omata (south-west of New Plymouth), outside FitzRoy's agreement. But three were in Te Āti Awa territory: the Mangorei or Grey block (south of the Fitzroy block), plus Cooke's Farm and the Bell Block (between New Plymouth and Waitara). These sales caused fighting among Māori who sold land and those who did not. But the Government succeeded. By 1859, it claimed to have bought a total of 30,000 hectares. The New Zealand Company had given up its charter in July 1850. All its land then went to the Crown (the government).

Grey's plan to get more land despite Māori opposition was clear from the start. In an 1847 letter, he said that apart from land set aside for Māori living there and those returning from the south, "the remaining portion... should be taken by the Crown for use by Europeans." In 1852, Donald McLean, the Inspector of Police, talked with Karira to buy Māori-owned land on the northern side of Mt. Taranaki. By 1855, the 58th Regiment was sent to New Plymouth to reassure the settlers.

On February 22, 1860, tensions grew over the sale of a 240-hectare (600-acre) piece of land at Waitara. This led to martial law (military rule) being declared in Taranaki. Settlers in nearby areas like Omata, Bell Block, and Waitara began building forts to protect their farms. Three weeks later, on March 17, Governor Thomas Gore Browne ordered a military attack on Te Āti Awa chief Wiremu Kīngi and his people at a defensive pā (fortified village) at Waitara.

New Plymouth During Wartime (1860–1866)

More than 3,500 soldiers came to Taranaki. These included regiments like the 65th, Suffolk, West Yorkshire, 40th, and 57th. New Plymouth became a fortified military town. Most women and children were sent to Nelson. The men joined the military forces. For over two years, all farming was done with military protection. Farmers returned to the safety of the many military forts at night. More than 200 farms were burned or robbed during the war. By July 1860, the town was reported to be under siege. One soldier wrote: "The natives have come close up to the town, murdering every soul who is fool enough to go half a mile outside the ramparts."

Disease was common because of extreme overcrowding. (121 people died from disease during the war, which was 10 times the usual number each year). Food was scarce, and settlers were almost giving up hope. Many feared the town would be attacked by Māori warriors. This was especially true when two strong pa were built within 3 kilometres of the town. The flow of new immigrants quickly stopped. In October 1860, a settler wrote: "Little remains of the settlement of Taranaki outside the 50 acre section to which the town is reduced."

The war ended with an uneasy peace after a year. However, later small battles, which some historians call a second Taranaki war, took place.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |