History of Rome (Livy) facts for kids

The History of Rome is a huge book about the past of ancient Rome. It was written in Latin by a Roman historian named Livy. He wrote it between 27 and 9 BC. The book is often called Ab Urbe Condita, which means "From the Founding of the City."

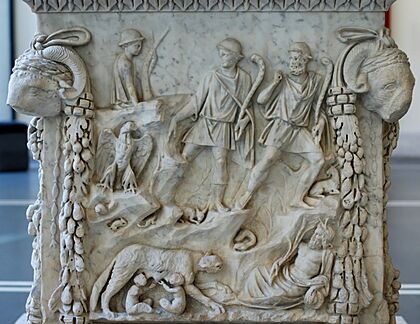

Livy's work tells the story of Rome from its very beginnings. It starts with the legends of Aeneas, a hero who came to Italy after the fall of Troy. It then covers the city's founding in 753 BC, when Romulus and Remus started it. It also tells about the time of the Kings and their removal in 509 BC. The story continues all the way to Livy's own time, during the rule of Emperor Augustus. The last event Livy wrote about was the death of Drusus in 9 BC.

Livy's original work had 142 "books," but only 35 of them are still around today. This is about a quarter of the whole history! The books we still have cover events up to 293 BC (books 1–10) and from 219 to 166 BC (books 21–45).

Contents

What's Inside Livy's History?

The Books We Still Have

Livy's History of Rome originally had 142 parts, called "books." We still have 35 of these books, from 1 to 10 and from 21 to 45. Some parts of books 41, 43, 44, and 45 are missing because old copies were damaged. These missing parts are called lacunae.

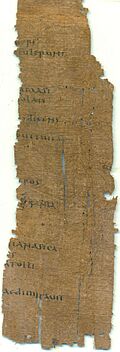

Sometimes, small pieces of lost books are found. For example, a tiny piece of book 91 was found in the Vatican Library in 1772. It had about a thousand words. Even smaller pieces of other lost books have been found in Egypt, like about 40 words from Book 11 in 1986.

We also know some things from the lost books because other ancient writers quoted Livy. A famous example is a quote about the death of Cicero, found in the writings of Seneca the Elder.

Short Versions of the History

In ancient times, people made shorter versions of Livy's huge work. These short versions are called an epitome. We have an epitome for Book 1. Later, in the 300s AD, even shorter summaries were made. These are called Periochae, and they are mostly just lists of what each book was about. We have the Periochae for almost all of Livy's original 142 books, except for books 136 and 137.

Some papyrus fragments found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, also contain summaries of Livy's books. One important fragment, called P.Oxy.IV 0668, has summaries of books 37–40 and 47–55.

Timeline of Rome's History in Livy's Books

Livy's History covers a very long time. Here's a simple timeline of what each group of books was about:

- Books 1–5: These books tell the legendary stories of Rome's founding. This includes Aeneas arriving in Italy and Romulus founding the city. They also cover the time when Rome had kings and the early years of the Roman Republic, until the Gauls attacked Rome in 390 BC.

- Books 6–10: These books describe Rome's wars with groups like the Aequi, Volsci, Etruscans, and Samnites. This period goes up to 292 BC.

- Books 11–20: This section covers the years from 292 to 218 BC, including the First Punic War (which Rome lost).

- Books 21–30: These books are all about the famous Second Punic War, from 218 to 202 BC.

- Books 31–45: This part describes Rome's wars in the east, like the wars against Macedon, from 201 to 167 BC.

The rest of the books, from 46 to 142, are now lost:

- Books 46–70: This period goes from 167 BC to the start of the Social War in 91 BC.

- Books 71–90: These books covered the civil wars between Marius and Sulla, up to Sulla's death in 78 BC.

- Books 91–108: This section describes events from 78 BC through the end of the Gallic War in 50 BC.

- Books 109–116: These books tell about the Civil War and the death of Julius Caesar (49–44 BC).

- Books 117–133: This part covers the wars of the triumvirs (three powerful Roman leaders) until the death of Mark Antony (44–30 BC).

- Books 134–142: The final books describe the rule of Emperor Augustus up to the death of Drusus in 9 BC.

Livy's Writing Style

Livy wrote his history by telling events year by year. He would often mention who the leaders (consuls) were, important events, and celebrations. This way of writing history, focusing on a yearly list of events, is called "annalistic history." Livy used this style to connect his work to older Roman traditions. It made his history feel continuous and strong.

The first and third groups of ten books (called "decades") are written so well that they are often studied in Latin classes today. Some people think Livy's writing quality went down in later books, becoming a bit repetitive. However, modern readers often appreciate how Livy used repeated phrases, especially when describing prayers or religious ceremonies.

In Book 9, Livy includes an interesting side story. He suggests that if Alexander the Great had lived longer and attacked Rome, the Romans would have beaten him. This is one of the oldest known examples of "alternate history" – imagining what might have happened differently.

How Livy's Work Was Published

Livy published his History in parts. The first five books came out between 27 and 25 BC. He kept working on the History for most of his life, releasing new parts as people wanted to read them. This is why the work naturally divides into groups, often of 10 books (called "decades") or sometimes 5 books ("pentads"). The idea of dividing the whole work into decades was something later copyists did.

For example, the second group of five books wasn't published until 9 BC or later, about 16 years after the first group.

Old Copies of Livy's Books

There isn't one simple way to name and sort all the old handwritten copies (called manuscripts) of Livy's work. Copying was done by hand, so mistakes could happen. To create a printed version, scholars had to compare many different manuscripts and try to figure out the most accurate text.

First Ten Books

Most of the manuscripts for the first ten books of Ab urbe condita come from a single corrected version made around 391 AD. A Roman official named Quintus Aurelius Symmachus asked a person named Victorianus to check and correct these books. Victorianus wrote on the copies that he had corrected them. This group of manuscripts is called the Nicomachean family, after Symmachus and his family members who were involved in the corrections.

Another important old copy of the first decade is the Verona Palimpsest. This is a manuscript where the original writing was scraped off and new text was written over it. Scholars were able to read the original Livy text underneath. This copy is from the 300s AD, which is only a few centuries after Livy wrote his history.

During the Middle Ages, there were many rumors that all of Livy's lost books were hidden in a monastery in Denmark or Germany. However, none of these rumors turned out to be true.

How Accurate is Livy's History?

Some experts believe that Livy was not a very good historian by today's standards. Here are some reasons why:

- He didn't do his own original research. He mostly used older histories that were already written.

- He sometimes repeated the same event twice.

- Some think his Greek language skills were not strong enough to fully understand one of his main sources, the Greek historian Polybius.

Livy's main goal was not just to list facts. He wanted to preserve a "memory" of Rome's past. He hoped his stories would teach readers about right and wrong through the actions of people from the past. His work also aimed to support the idea that the rule of Emperor Augustus was the best outcome for Roman history.

Modern experts also point out that Livy's battle descriptions can be unclear. His geography can be vague, and he sometimes showed too much favor to his "heroes." His speeches and dramatic stories are also very grand and dramatic.

However, we only have about a third of Livy's complete work. The parts we have might not show how he wrote about later periods of Roman history or his own time. For those periods, he might have done more original research, using eyewitness accounts or official records.

Truth in the Stories

The details in Livy's History change from legendary and mythical stories at the beginning to more detailed accounts of real events later on. Livy himself knew it was hard to write about Rome's early history. He said that stories from before Rome was founded were "more fitted to adorn the creations of the poet than the authentic records of the historian."

Livy recognized that the early years of Rome were full of myths. For example, his first book is a key source for the famous legend of Romulus and Remus. But when he wrote about the Roman Kingdom, he left out many stories that seemed unlikely to him. Even so, the early parts of his books are important sources for understanding how ancient people viewed early Rome.

Livy knew that older writers were usually more reliable. But he didn't always make sure his own history was perfectly consistent. He often preferred to tell a good story, even if he later found mistakes.

Livy mostly arranged and combined information from his sources. He didn't do much original research using official documents. He tried to fix differences in his sources by guessing what was most likely. However, he didn't really consider that some older writers might have just made up probable stories. Livy also rarely named his sources, especially in long sections where he followed one main source. Luckily, Livy's goal was to tell existing stories with "better style and arrangement," so he probably didn't invent new events or exaggerate things too much.

Where Livy Got His Information

Livy's work came after a long line of Roman historians. These earlier historians are often called the "annalistic tradition." When Livy used these sources, his main rule was to "tell what he had been told."

Roman history writing goes back to Quintus Fabius Pictor, who wrote around 200 BC. Other early Roman historians included Cato the Elder and Gnaeus Gellius. Some later historians from the 1st century BC, like Valerius Antias and Licinius Macer, are thought to have been less careful. They might have made up stories about ancient times.

Livy did not use very old official records like the libri lintei (linen books) or the annales maximi (greatest annals) kept by the chief priest. He also didn't travel around Rome looking for old writings or documents. It was hard to use the Senate's own records back then, and there were even hints that evidence could be faked.

Later Influence

Machiavelli's Work

Niccolò Machiavelli, a famous writer, wrote a book called Discourses on Livy. This book is presented as a discussion and commentary on Livy's History of Rome.

Translations of Livy

The first full English translation of Ab urbe condita was done by Philemon Holland in 1600. It was a very important and large book.

Other notable translations include B.O. Foster's History of Rome from 1919 and a partial translation by Aubrey de Sélincourt for Penguin Classics in the 1960s.

See also

In Spanish: Ab urbe condita (libro) para niños

In Spanish: Ab urbe condita (libro) para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |