History of Sarawak facts for kids

The History of Sarawak tells the story of this amazing place, starting from about 40,000 years ago! That's when the first signs of people living here were found in the Niah Caves. Later, between the 8th and 13th centuries AD, Chinese pottery was discovered at an old trading spot called Santubong.

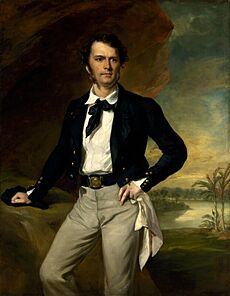

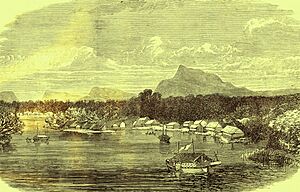

Around the 16th century, the coastal parts of Sarawak were influenced by the Bruneian Empire. Then, in 1839, a British explorer named James Brooke arrived. His family, the Brooke family, ruled Sarawak for a long time, from 1841 to 1946.

During World War II, Japanese forces took control of Sarawak for three years. After the war, the last ruler from the Brooke family, Charles Vyner Brooke, gave Sarawak to Britain. It became a British colony in 1946. On 22 July 1963, Sarawak gained self-government from the British. Soon after, on 16 September 1963, it became one of the first members of the new country, Malaysia. However, this new federation led to a three-year conflict with Indonesia. Sarawak also faced a communist uprising from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Contents

Ancient Times: Early People in Sarawak

Scientists now believe that the first people arrived at the Niah Caves about 65,000 years ago. This was much earlier than thought! Back then, the island of Borneo was connected to mainland Southeast Asia. The area around Niah Caves was drier and more open than it is today.

These early people were foragers. They survived by hunting, fishing, and gathering things like shellfish and plants they could eat. In 1958, a very old human skull, nicknamed "Deep Skull," was found in the Niah Caves. It's the oldest modern human skull found in Southeast Asia! This skull belonged to a teenage girl, about 16 or 17 years old. It looks a lot like the people who live in Borneo today.

Other ancient burial sites from the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods have also been found here. The area around the Niah Caves is now a special place called Niah National Park.

Early Trading Hubs

Another important discovery was made in 1949 at Santubong, near Kuching. Here, Chinese pottery from the Tang and Song dynasties (8th to 19th centuries AD) was found. This suggests that Santubong was a very important seaport in Sarawak during that time. However, its importance faded later, and the port was abandoned during the Ming dynasty.

Other old places where archaeological finds have been made include the Kapit, Song, Serian, and Bau districts.

Early Kingdoms and Trading Ports

Before the modern history of Sarawak, there were several small kingdoms. These included Santubong (near Kuching), Sadong (near Samarahan), Saribas, and Kalaka (both in Betong Division). There was also Malano (in Mukah), and Banting and Lingga (in Sri Aman).

Archaeological digs at Santubong show it was a busy trading port from the 7th to the 14th century. They found Chinese pottery, lots of iron waste (about 40,000 tonnes!), and items related to the Hindu religion. The name Santubong was later changed to Sawaku (Sarawak), as mentioned in an old Javanese book called Nagarakretagama.

People from Santubong might have moved inland to the Gedong/Sadong areas. Old records also mention a state called Samarahan, sometimes known as Sadong. Many Chinese ceramic pieces and other treasures from the 14th to 17th centuries have been found in these inland areas, showing that trade happened far from the coast.

Other kingdoms like Kalaka and Saribas were also important. Kalaka was mentioned in the Nagarakretagama as a colony of the Majapahit Empire. The Saribas kingdom had its own leaders and history, with stories of a Bruneian dignitary named Pengiran Temenggong Abdul Qadir setting up a capital there.

The Melano kingdom existed from about 1300 to 1400 AD, centered around the Mukah river. Its most famous ruler was Rajah Tugau. This kingdom included groups of people who spoke similar languages, like Melanau and Kajang, and shared similar cultures. It covered the coastal areas of Sarawak up to Belait.

By 1530, European mapmakers knew the Santubong area as Cerava, one of the five big seaports on Borneo. Maps from the 16th and 17th centuries show places like Cereua (Santubong), Belanos (Melano), and Sedang (Sadong). These maps and old reports confirm that Sarawak's coastal areas were active trading spots long ago.

Bruneian Influence and the Sultanate of Sarawak

During its powerful period, the Bruneian Empire, led by Sultan Bolkiah (1473-1521 AD), conquered the Santubong Kingdom in 1512.

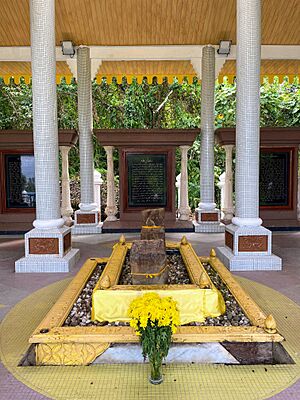

Later, in 1599, a Brunei prince named Pengiran Muda Tengah was made the Sultan of Sarawak. At that time, Sarawak was a territory managed by Brunei. Sultan Tengah ruled until 1641 when he was sadly killed. He was buried in Kampong Batu Buaya. After his death, the Sultanate of Sarawak ended, and the area became part of the Bruneian Empire again.

By the early 1800s, Sarawak was not very well controlled by the Brunei Sultanate. Brunei's power was mostly along the coast, where local Malay leaders had some authority. The inland areas of Sarawak often had tribal wars between groups like the Iban, Kayan, and Kenyah people, who were trying to expand their lands.

James Brooke Arrives

When antimony ore was found near Kuching, a Brunei official started to develop the area. As antimony production grew, the Brunei Sultanate demanded more taxes, which led to unrest and chaos. In 1839, the Sultan of Brunei asked his uncle, Pengiran Muda Hashim, to restore order.

Pengiran Muda Hashim asked a British sailor named James Brooke for help. Brooke first refused, but when he visited Sarawak again in 1841, he agreed. Pengiran Muda Hashim signed a treaty in 1841, giving control of Sarawak to Brooke. On 24 September 1841, James Brooke was made governor. The Sultan of Brunei confirmed this in 1842.

Brooke later used his influence to make sure Pengiran Muda Hashim was appointed to the Brunei Court. This made the Brunei Court unhappy, and Hashim was killed in 1845. In response, James Brooke attacked Brunei's capital. After this, the Sultan of Brunei apologized to Queen Victoria and confirmed James Brooke's ownership of Sarawak and his right to mine antimony without paying taxes. In 1846, James Brooke officially became the Rajah of Sarawak, starting the "White Rajah Dynasty."

Iban People Move to Sarawak

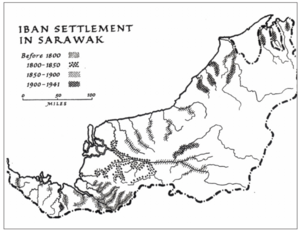

According to their old stories, the Iban people originally came from the Kapuas River in what is now Indonesian Borneo. They moved to Sarawak because of problems in their homeland. Modern language and cultural studies also support that the Iban language and culture started in the upper Kapuas region.

Studies show that the Iban migrations to Sarawak began around the 1750s. The first groups arrived in Batang Lupar and settled near the Undop River. Over a few generations, the Iban people from Batang Lupar spread out to the north, east, and west, creating new communities.

During the time of the White Rajahs in the 1800s, many Ibans moved north towards the Rejang Basin. By the 1870s, a large Iban community was recorded near Mukah and Oya river. By the early 1900s, Iban pioneers reached Tatau, Kemena (Bintulu), and Balingan. They also expanded to the Baram valley and Limbang River in northern Sarawak.

The Brooke government sometimes had problems with the Iban migrations. The Iban communities could easily outnumber other tribes and their farming methods sometimes affected the land. Because of this, the government tried to limit Iban movement to other river systems. There were some tensions between the Iban people and the Brooke government's rules, especially in the Balleh Valley.

However, the migrations also created opportunities. The Ibans were very skilled at finding forest products like camphor, rattans, wild rubber, and damar. The government eventually allowed permanent Iban settlements in newly acquired territories. For example, when Limbang was added to Sarawak in 1890, the Ibans were encouraged to settle there.

By the late 1800s, some areas like Batang Lupar and Skrang Valley became overpopulated. So, the Sarawak government started a program to open up new territories for Iban settlements, with certain conditions. This led to more Ibans moving to Baram, Balingan, and Bintulu.

This government plan helped the Iban language and culture spread throughout modern Sarawak. It also affected other local groups. For instance, some Bukitan leaders in Batang Lupar married into Iban families, causing their communities to become part of Iban society. However, other groups, like the Ukits, Seru, Miriek, and Biliun, faced tougher situations, and their traditional communities were almost replaced by the Ibans.

The Brooke Dynasty: White Rajahs of Sarawak

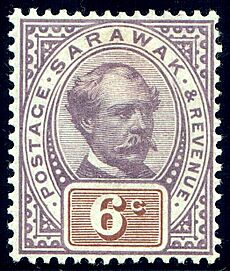

James Brooke ruled Sarawak and expanded its territory northwards until he passed away in 1868. His nephew, Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke, took over. Later, Charles Anthoni's son, Charles Vyner Brooke, became the next Rajah.

Both James and Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke pushed Brunei to sign agreements to gain more land for Sarawak. In 1861, Brunei gave the Bintulu region to James Brooke. Sarawak was recognized as an independent state by the United States in 1850 and the United Kingdom in 1864. Sarawak even started printing its own money, the Sarawak dollar, in 1858.

Sarawak continued to grow. In 1883, its borders reached the Baram River (near Miri). Limbang was added in 1890, and the final expansion happened in 1905 when Lawas became part of Sarawak. The country was divided into five main areas, called divisions, each led by a British Resident.

In 1888, Sarawak became a British protectorate, meaning Britain would protect it, but the Brooke family still ruled. The Brookes were known as "White Rajahs" and governed Sarawak for a hundred years. They tried to protect the local people and their well-being. The Brooke government created a Supreme Council, made up of Malay chiefs, who advised the Rajahs on how to run the country. This Supreme Council is the oldest state legislative assembly in Malaysia, with its first meeting in Bintulu in 1867.

The Brooke dynasty encouraged Chinese merchants to come to Sarawak to help the economy, especially in mining and farming. They banned piracy, slavery, and headhunting. A company called Borneo Company Limited was formed in 1856 and was involved in many businesses in Sarawak, like trade and mining.

In 1857, about 500 Chinese gold miners from Bau rebelled and destroyed the Brookes' house. James Brooke escaped and, with the help of his nephew Charles and local supporters, defeated the rebels. The Brookes then built a new government house, The Astana, by the Sarawak River in Kuching. Other rebellions, like those led by Iban leader Rentap and Malay leader Syarif Masahor, were also put down. To strengthen their power, the Brookes built forts around Kuching, including Fort Margherita, completed in 1879.

In 1891, Charles Anthoni Brooke founded the Sarawak Museum, the oldest museum in Borneo. He also ended inter-tribal wars in Marudi in 1899. The first oil well was drilled in 1910, and the Brooke Dockyard opened two years later.

In 1941, during the 100th anniversary of Brooke rule, a new constitution was introduced. It aimed to limit the Rajah's power and give the people of Sarawak a bigger role in government. However, there was a secret agreement that Charles Vyner Brooke would give Sarawak to Britain as a British Crown Colony in exchange for money for his family.

World War II and Japanese Occupation

Before World War II, the Brooke government built several airstrips in places like Kuching and Miri to prepare for war. By 1941, the British had moved their defending forces from Sarawak to Singapore, leaving Sarawak unprotected. The Brooke government decided to destroy oil facilities in Miri and hold the Kuching airfield as long as possible before destroying it.

Japanese forces invaded British Borneo to protect their operations in the Malayan Campaign. A Japanese invasion force landed in Miri on 16 December 1941 and took Kuching on 24 December 1941. British forces retreated and eventually surrendered on 1 April 1942. When the Japanese invaded, Charles Vyner Brooke had already left for Australia, and his officers were captured and held at the Batu Lintang camp.

Sarawak was under Japanese rule for three years and eight months. It became part of a larger administrative unit called Kita Boruneo (Northern Borneo), with its headquarters in Kuching. The Japanese kept some of the pre-war government structure but put Japanese officials in charge. They mostly left the interior of Sarawak to local police and village leaders, under their supervision.

While many Malays were open to the Japanese, other local tribes like the Iban and Kayan were hostile. This was because of policies like forced labor, forced food deliveries, and taking away their weapons. The Japanese were less strict with the Chinese population, who were generally not involved in politics. However, many Chinese moved from cities to the countryside to avoid contact with the Japanese.

Allied Liberation

Later in the war, the Allied forces created a special unit called Z Special Unit to disrupt Japanese operations. Starting in March 1945, Allied commanders parachuted into the Borneo jungles and set up bases in Sarawak as part of an operation called "Semut." Hundreds of local people were trained to fight against the Japanese.

During the battle of North Borneo, Australian forces landed in the Lutong-Miri area on 20 June 1945 and pushed into Marudi and Limbang. After Japan surrendered, the Japanese forces in Borneo surrendered to the Australians at Labuan on 10 September 1945. The official surrender ceremony in Kuching took place on 11 September 1945. The Batu Lintang camp was freed on the same day. Sarawak was then managed by the British Military Administration until April 1946.

-

A map of the occupation of Borneo in 1943 prepared by the Japanese during World War II.

-

A large crowd of Sarawak people in Kuching watching the arrival of Australian Imperial Force (AIF) soldiers on 12 September 1945.

-

A large world map, showing the Japanese-occupied area in Asia, set up in the main street of Sarawak's capital.

Sarawak Becomes a British Colony

After World War II, the Brooke government didn't have enough money or resources to rebuild Sarawak. Charles Vyner Brooke also didn't want to hand over power to his nephew, Anthony Brooke, who was supposed to be his heir. Because of these problems, Vyner Brooke decided to give Sarawak to the British Crown.

A bill to make Sarawak a British colony was debated in the Council Negri (now the Sarawak State Legislative Assembly). It passed on 17 May 1946, but only by a small number of votes (19 for, 16 against). Most European officers supported the bill, while many Malays were against it. This led to hundreds of Malay civil servants resigning in protest. It also sparked an anti-cession movement and the assassination of the second British colonial governor, Sir Duncan Stewart, by Rosli Dhobi.

Anthony Brooke was against Sarawak becoming a British colony and was linked to the anti-cession groups. He continued to claim he was the rightful ruler of Sarawak even after it became a British Crown colony on 1 July 1946. Because of this, the colonial government banned him from Sarawak. He was only allowed to return 17 years later for a visit, after Sarawak had become part of Malaysia. By 1950, all anti-cession movements in Sarawak stopped after the colonial government took strong action. In 1951, Anthony gave up all his claims to the Sarawak throne.

Self-Government and Joining Malaysia

On 27 May 1961, Tunku Abdul Rahman, the prime minister of the Federation of Malaya, suggested forming a bigger country called Malaysia. This new country would include Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei.

Local leaders in Sarawak were worried about this plan. They feared that without strong political power, Sarawak would be controlled by Malaya, which was more developed. So, different political parties in Sarawak were formed to protect the interests of their communities.

To find out what people in Sarawak and Sabah thought, the Cobbold Commission was set up on 17 January 1962. Between February and April 1962, the commission met over 4,000 people and received 2,200 suggestions. The report showed that people in Borneo had mixed feelings, but Tunku Abdul Rahman interpreted it as 80 percent support for the federation. Sarawak proposed an 18-point memorandum to make sure its interests were protected in the new federation.

In September 1962, the Sarawak Council Negri (now the Sarawak state legislative assembly) voted to support the federation, but only if Sarawak's interests were not harmed. On 23 October 1962, five political parties in Sarawak formed a united group to support Malaysia. Sarawak was officially granted self-government on 22 July 1963. Then, on 16 September 1963, it joined Malaya, North Borneo, and Singapore to form the Federation of Malaysia.

Confrontation and Communist Uprising

The formation of Malaysia was opposed by the Philippines, Indonesia, the Brunei People's Party, and some communist groups in Sarawak. The Philippines and Indonesia claimed that Britain was trying to control the Borneo states through the new federation.

In December 1962, the leader of the Brunei People's Party, A. M. Azahari, started the Brunei Revolt to stop Brunei from joining Malaysia. His forces took over Limbang and Bekenu but were defeated by British troops. Indonesian President Sukarno used this revolt as an excuse to start a military conflict with Malaysia, known as the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (1962-1966). Sarawak became a key battleground.

The confrontation didn't get much support from most Sarawakians, except for the Sarawak communists. Thousands of communists went to Indonesian Borneo for training. During this time, many British, Australian, and New Zealand troops were stationed in Sarawak. When Suharto replaced Sukarno as Indonesia's president, talks began, and the confrontation ended on 11 August 1966.

After the formation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, communist ideas began to influence Chinese schools in Sarawak. The first communist group in Sarawak was formed in 1951. This group, later called the Sarawak Liberation League (SLL), spread its activities from schools to trade unions and farmers. They were mainly in the southern and central parts of Sarawak.

During the confrontation with Indonesia, the SLL started fighting the government with weapons. Two important leaders were Weng Min Chyuan and Bong Kee Chok. The Sarawak government moved Chinese villagers into guarded settlements to prevent them from helping the communists. The North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP) was officially formed in 1970.

In 1973, Bong Kee Chok surrendered to Chief Minister Abdul Rahman Ya'kub, which greatly weakened the communist party. However, Weng Min Chyuan, who had been directing the NKCP from China, called for continued armed struggle. This continued in the Rajang Delta after 1974.

In 1989, the Malayan Communist Party signed a peace agreement with the Malaysian government. This led the NKCP to restart talks with the Sarawak government, resulting in a peace agreement on 17 October 1990. Peace finally returned to Sarawak when the last group of 50 communist guerrillas laid down their arms.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |