History of Seattle before 1900 facts for kids

The early history of Seattle has two main stories. One story focuses on the Denny Party (families like Denny, Mercer, Terry, and Boren) and Henry Yesler. They are often seen as the main founders. The other story, told by historians like Bill Speidel and Murray Morgan, highlights David Swinson "Doc" Maynard as a very important person.

The Denny Party members were generally more traditional and held powerful positions as Seattle grew. Doc Maynard was older and passed away sooner, so he wasn't around to share his side of the story as much. The Denny Party was often against alcohol, while Maynard was not. He was also friendly with the local Native Americans, which was different from many in the Denny Party. Because of these differences, Maynard was almost forgotten in Seattle's history until later historians brought his story to light.

Contents

Founding of Seattle

What is now Seattle has been home to people for at least 10,000 years, since the end of the last Ice Age. Scientists have found proof of settlements within the city limits from at least 4,000 years ago. The Dkhw'Duw'Absh (People of the Inside) and Xachua'bsh (People of the Large Lake) were Coast Salish Native American groups. They lived in at least 17 villages in the mid-1850s, with 13 of these villages inside what is now Seattle. They lived in large longhouses along the Duwamish River, Elliott Bay, and Lake Washington. Today, these groups are represented by the Duwamish Tribe.

George Vancouver was the first European to visit the Seattle area in May 1792. He was exploring the Pacific Northwest. The first White settlers began looking for places to live here in the 1830s.

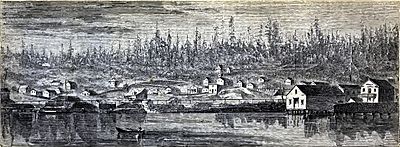

The founding of Seattle is usually marked by the arrival of the Denny Party on November 13, 1851, at Alki Point. This group traveled from the Midwest to Oregon, then sailed up the coast to Puget Sound. Their goal was to start a new town. The next April, Arthur A. Denny moved from Alki to a better, more protected spot on Elliott Bay, which is now part of Downtown Seattle. Around the same time, Doc Maynard began settling land just south of Denny's. While some stayed at Alki for a few years, it became clear that Maynard and Denny had chosen the best location.

The first official maps for Seattle were made on May 23, 1853. Doc Maynard's land was south of what is now Yesler Way, covering much of today's Pioneer Square and the International District. His streets followed the compass directions. The land claimed by Arthur A. Denny and Carson D. Boren was north of Yesler Way, including the heart of downtown. Their streets followed the shoreline. This is why some streets in downtown Seattle don't line up perfectly!

Both Alki and early Seattle depended on the timber industry. They shipped logs and lumber to help rebuild San Francisco, which often had fires. Seattle had many tall trees, some as old as 1,000 to 2,000 years and nearly 400 feet tall. These trees were perfect for building. Today, no trees of that size remain anywhere in the world.

Relations with Native Americans

The early settlers in Seattle had a difficult relationship with the local Native Americans. The settlers were constantly taking over Native lands, and often treated the Native people poorly. There were many attacks between settlers and Native Americans.

Historian Bill Speidel wrote that many settlers believed that "killing an Indian was a matter of no graver consequence than shooting a cougar or a bear." In this difficult time, Doc Maynard was different because he had good relationships with Native Americans. He and Chief Seattle were friends. Maynard certainly gained from this friendship, but he also risked the anger of other settlers by protecting neutral Native people during conflicts.

Some settlers, like Denny and federal judge Edward Lander, believed that the law should apply to everyone, no matter their race. However, it was hard to get juries to agree with this view.

Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens caused many problems between settlers and Native Americans. He offered rewards for the scalps of "bad Indians." He also made dishonest promises in treaties, saying one thing but writing another. The local Native Americans had a history of fair dealings with the Hudson's Bay Company, so they were not prepared for Stevens' behavior. Treaties like the Medicine Creek Treaty (December 26, 1854) and the Point Elliott Treaty (January 22, 1855) were unfair and confusing.

After the Point Elliott Treaty

Before the Treaty of Point Elliott, Maynard had already become friends with Chief Seattle. He arranged for Chief Seattle to be paid for the use of his name for the new town. This was important because in Coast Salish culture, it was not simple to use a person's name after their death. At Point Elliott, Maynard helped Chief Seattle and the Duwamish get a separate, more favorable treaty. This treaty promised a large reservation in exchange for Native people giving up their claim to land that is now almost the same size as modern Seattle. However, this promised reservation was never fully given.

As Governor Stevens caused trouble in Eastern Washington, Secretary of State Charles Mason was in charge of the state government. Yakama Chief Kamiakim had declared war and told groups like the Duwamish that they had to join him or be seen as enemies. By autumn, both sides were attacking each other, often without caring if the specific individuals had done anything wrong.

Maynard became a Special Indian Agent. He used money from selling land to buy supplies and a boat. He then used the boat to take Chief Seattle and his Duwamish people to a safe, privately funded reservation at Port Madison. Maynard also traveled around eastern King County, warning other neutral Native Americans that there was a safe place for them to go. Most of them went with him.

Some Seattle businessmen, like Henry Yesler, were not happy about Maynard moving the local Native Americans. They lost many of their workers and complained to the government.

On January 25, 1856, Governor Stevens claimed that Seattle was in danger of an attack. The next day, January 26, 1856, Native Americans attacked the Seattle settlement. Friendly Native people who were allowed to stay in Seattle had warned the settlers. The town was defended by a large wooden blockhouse, a protective wall, and a ship called the Decatur with its cannons. The attackers were driven off, and they seemed to decide that attacking a major settlement was not worth it.

After the "Battle of Seattle"

Even after the main fighting stopped, Governor Stevens continued his efforts against Native Americans. He encouraged fighting between different Native groups by offering rewards for the scalps of "bad Indians." Chief Patkanim, a leader of the Snoqualmie and Snohomish, collected the most rewards.

Stevens tried to get Chief Seattle and the Duwamish to join this cause. But Maynard and Chief Seattle found ways to avoid sending Duwamish fighters to help Stevens.

The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic killed about half of the Native population. Government policies made the epidemic worse for Native people.

Later, in 1866, the Seattle leaders, including Doc Maynard, asked the government to deny treaty rights to the Duwamish. The promises made by the United States government in the Point Elliott Treaty have still not been fully kept.

Yesler's Mill

At first, Alki was bigger than Seattle. But when Henry Yesler decided to build a steam sawmill, he chose a Seattle location. It was on the waterfront where Maynard and Denny's land met. After that, Seattle became the center of the lumber industry.

Yesler chose Seattle because Alki had a major problem as a port. Strong north winds in winter created huge waves that made it impossible to build anything lasting in the water at Alki Point.

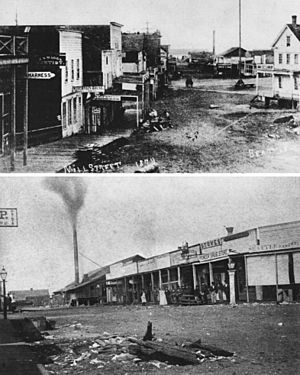

The road leading down the hill to Yesler's mill was called the Skid Road. This was where logs were "skidded" or slid down to the mill. This is where the term "Skid Row" comes from, meaning a run-down area, as the mill area later declined.

Yesler used his mill's power to get a large piece of valuable land from the original settlers. Besides his mill, Yesler started a cookhouse. This cookhouse helped make Yesler's land the heart of the city. Yesler didn't make a lot of money from his mill itself, but the great location of his land made him very wealthy.

A City Grows

Seattle's first wealth came from logs and lumber shipped south to build San Francisco. In its early years, Seattle itself was mostly made of wooden buildings. Even the water pipes were hollowed-out logs.

Charles C. Terry sold his land at Alki and moved to Seattle, where he bought more land. He owned some of the first ships that helped Seattle's timber industry by moving products to market. He also gave land for the University of the Territory of Washington. This land grant still helps the University of Washington today by providing income from rents. Terry also worked in politics to help set up street levels and a water system, which also helped him as a large landowner.

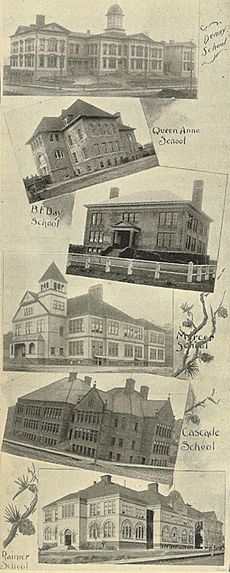

Arthur Denny became the second richest man in town, after Yesler. He was elected to the territorial legislature. He tried to move the capital to Seattle from Olympia, but he didn't succeed. Seattle did, however, get the university. The legislature required a 10-acre land grant for the university. Denny wanted his town to grow, so he donated the land. The University of the Territory of Washington (later the University of Washington) opened on November 4, 1861.

Seattle grew quickly from a logging town into a small city. Even though it was founded by traditional Methodists, Seattle quickly became known as a "wide-open" town with many businesses. Doc Maynard is thought to have played a part in this. He sold some of his land cheaply, but only if businesses were built on it quickly. This brought in various professionals and businesses, which made his remaining land more valuable. Records show that most of the city's first 60 businesses were on or near Maynard's land.

Seattle officially became a town on January 14, 1865. It was re-incorporated as a city on December 2, 1869. At these times, the population was about 350 and 1,000 people.

Railroad Rivalry and City Improvements

On July 14, 1873, the Northern Pacific Railway announced that it had chosen the small town of Tacoma as the western end of its transcontinental railroad, not Seattle. The railroad owners likely wanted to buy land cheaply around their chosen end point.

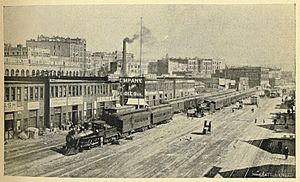

Seattle citizens didn't want to be left out. They started their own railroad, the Seattle & Walla Walla, to connect with another railroad in eastern Washington. This railroad helped connect Seattle to new coal mines, which powered Seattle's industries. Later, the Great Northern Railway chose Seattle as the end point for its transcontinental line in 1893. This helped Seattle become a major city for shipping goods.

In this era, Seattle was known as a "wild" town. While it had newspapers and telephones, basic services were lacking. Schools barely operated, and indoor plumbing was rare. In the low, muddy areas where much of the city was built, sewage often flowed back in with the tide.

Women in Seattle tried to bring more order and civility to the city. On April 4, 1884, 15 women founded The Ladies Relief Society to help those in need. This group eventually started the Seattle Children's Home, which still exists today.

Other signs of progress included the city's first bathtub with plumbing in 1870, and its first streetcar in 1884. In 1885, the city required new homes to have sewer lines. In 1888, ferry service began, connecting Seattle to West Seattle. A year later, a bridge was built across Salmon Bay, connecting to the nearby town of Ballard, which later became part of Seattle.

Seattle and Tacoma both grew quickly from 1880 to 1890 because of their timber industries. However, Seattle continued to grow for another two decades by exporting services and manufactured goods, while Tacoma's growth slowed. This was because Tacoma was mainly a "company town" focused on lumber, while Seattle had a more varied economy. Seattle became the main center for the region, and the railroads eventually had to come there.

Relations between White and Chinese Residents

Chinese people first arrived in Seattle around 1860. After the Northern Pacific Railway finished laying tracks in 1883, many Chinese laborers lost their jobs. In 1883, Chinese workers helped dig the Montlake Cut to connect Lake Union to Lake Washington.

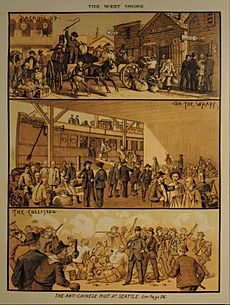

Seattle's Chinese district was a mixed neighborhood with homes above stores and laundries. In the fall of 1885, with fewer jobs available, many workers became angry at Chinese laborers, complaining that they worked for too little money. In the Pacific Northwest, anti-Chinese groups included both Native Americans and European-Americans.

There were attacks on Chinese people in other areas. On October 24, 1885, a large part of Seattle's Chinatown was burned by a mob. On November 3, a mob of 300 people forced Chinese residents out of Tacoma.

Labor unions were often involved in the anti-Chinese movement. Many white laborers saw cheap Chinese labor as their main competition. Even wealthy people, while not supporting violence, often wanted Chinese people to leave in an orderly way. Mayor Henry Yesler supported this.

A few people, like the Methodist Episcopal Ministers' Association and Judge Thomas Burke, defended the rule of law. Judge Burke, an Irish immigrant, believed his fellow Irish should understand the Chinese as fellow immigrants.

On February 7, 1886, organized anti-Chinese groups went into Seattle's Chinatown. They claimed to be health inspectors and said Chinese buildings were unsafe. They forced residents to the harbor, where a ship called the Queen of the Pacific was docked. The police tried to prevent physical harm but didn't stop the mob from forcing people out. The mob raised money to pay for 86 Chinese people to board the ship. However, this delay gave the mayor, Judge Burke, and others time to gather the local guard and stop the ship from leaving with the Chinese. A plan to send Chinese people away by train was also stopped.

The next day, a judge made it clear that Chinese people who wanted to stay would be protected. But after what they had been through, almost all of them chose to leave. A scuffle broke out, leading to one death and four injuries among the anti-Chinese group. Martial law was then put in place. In the end, most of the Chinese people remained in Seattle. The U.S. government later paid the Chinese government over $276,000 for the damages, but the victims themselves received nothing.

The Great Seattle Fire

The early era of Seattle ended suddenly with the Great Seattle Fire on June 6, 1889. The fire burned 29 city blocks, destroying most of the central business district. Luckily, no one died in the fire, and the city recovered very quickly. Seattle rebuilt with amazing speed. New building rules meant that downtown was rebuilt with brick and stone buildings instead of wood. In the year after the fire, the city grew from 25,000 to 40,000 people, largely because of all the new construction jobs.

Labor History in 19th Century Seattle

The economy of the Pacific Northwest in the 1800s was heavily based on industries that took natural resources, mainly logging. As Seattle grew into a city, labor unions began to form. In 1882, printers in Seattle formed their union. Dockworkers followed in 1886, cigar makers in 1887, and other skilled workers like tailors, brewers, and musicians also formed unions. Even newsboys formed a union in 1892.

The history of labor unions during this time is closely linked to the anti-Chinese actions. White laborers in Seattle saw cheap Chinese labor as their main competition. They tried to get rid of this competition by forcing Chinese immigrants out of the area.

The Klondike Gold Rush

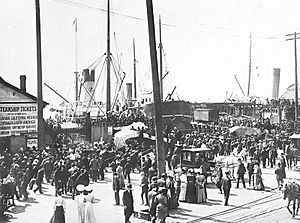

Seattle, like the rest of the country, faced tough economic times in the 1890s. But it found a solution by becoming the main center for people heading to the Klondike gold rush. On July 17, 1897, a ship arrived in Seattle carrying a "ton of gold" from Alaska. This news made Seattle famous overnight. A clever advertising campaign convinced people around the world that Seattle was the best place to get supplies for the journey to Alaska. The miners dug for gold, and Seattle made money from the miners.

Seattle's relationship with Alaska during this time was often about taking advantage. For example, in 1899, a group from Seattle proudly showed off a 60-foot totem pole in Pioneer Square. The problem was, the pole had been stolen from a Tlingit village in Alaska. A court in Alaska charged eight important Seattle citizens with theft. They paid a small fine. The village was later paid back when the original pole burned down and Seattle ordered a replacement. The village leaders wrote, "Thank you for the check. That was payment for the first one. Send another check for the replacement."

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |