- This page was last modified on 17 October 2025, at 10:18. Suggest an edit.

History of Washington & Jefferson College facts for kids

The history of Washington & Jefferson College is a story that started with three small log cabin schools in the 1780s. These schools were founded by three frontier ministers: John McMillan, Thaddeus Dod, and Joseph Smith. All three had studied at the College of New Jersey. They came to what is now Washington County to start churches and share their faith, Presbyterianism, in the American frontier.

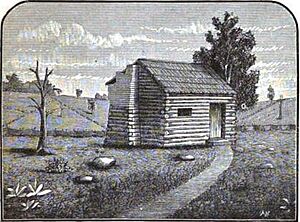

John McMillan was the most well-known of the three founders. He arrived in the area in 1775 and built his log cabin school in 1780 near his church in Chartiers. Thaddeus Dod, a very smart scholar, built his school in Lower Ten Mile in 1781. Joseph Smith taught classic subjects in his school, called "The Study" at Buffalo.

Washington Academy was officially started by the Pennsylvania General Assembly on September 24, 1787. Reverends Dod and Smith were among its first leaders. After a long search, they chose Thaddeus Dod as the headmaster. He was considered the best scholar in western Pennsylvania. The academy faced money problems and challenges from the Whiskey Rebellion. Because of this, it didn't hold classes from 1791 to 1796. In 1792, the academy got land and started building the stone Academy Building.

In 1792, McMillan was chosen as the headmaster for "Canonsburg Academy," located in Canonsburg. This happened after a delay due to "trouble with Indians." McMillan later moved his students from his log cabin school to Canonsburg Academy. Canonsburg Academy was officially recognized by the General Assembly on March 11, 1794. This put it ahead of Washington Academy, which was struggling. On January 15, 1802, the General Assembly finally approved a charter for "a college at Canonsburgh," with McMillan leading the board.

In 1802, Canonsburg Academy became Jefferson College. John McMillan was the first president of its board. In 1806, Matthew Brown helped Washington Academy get its own college charter, renaming it Washington College. For the next 60 years, both colleges tried to join together many times. But they couldn't agree on where the combined college would be located. In 1817, a big disagreement over a possible merger led to "The College War." This event almost destroyed both colleges.

After the Civil War, both colleges had fewer students and less money. This led them to finally join together as Washington & Jefferson College in 1865. The new college was supposed to operate in both Canonsburg and Washington. This caused many problems for the leaders trying to save the college. In 1869, the two-campus plan was declared a failure. All operations moved to Washington. However, a lawsuit was filed by people in Canonsburg who wanted to stop the merger. This case eventually went all the way to the United States Supreme Court. By 1871, the Supreme Court supported the merger, allowing the new college to continue.

Under James D. Moffat, the college grew a lot. Between 1922 and 1931, during the time of Simon Strousse Baker, many new buildings were constructed. There was also student unrest, which led to his resignation. During World War II, the college became a training facility for the United States Army. After the war, many veterans attended, making the student body larger than ever before. In 1970, the college decided to admit women for the first time.

From 1998 to 2004, Brian C. Mitchell was president. He oversaw more construction and worked to improve the college's relationship with the nearby communities. In 2004, Tori Haring-Smith became the first woman president of Washington & Jefferson. She focused on making the campus more international. She brought in more international students and started the Magellan program, which sends students abroad for independent study. She also built the Swanson Science Center and the Ross Family Athletic Center. During her time, she raised over $250 million for the college. She retired in 2017.

Contents

Three Log Colleges: The Beginnings

Washington & Jefferson College started with three log cabin schools. These were founded by three ministers in the 1780s: John McMillan, Thaddeus Dod, and Joseph Smith. They were all graduates of the College of New Jersey. They came to Washington County to start churches and spread their faith. These men worked well together, even though they had different personalities. McMillan was the organizer, Dod was the scholar, and Smith was the preacher.

Early students faced attacks from local Indian tribes. They were also greatly influenced by religious revivals. Women from five local churches made clothes for the students. Many students were farmers or veterans of the Revolution. Most went to school to become ministers. Many later moved west to spread their faith to other settlers and even to the same Native American tribes. These three log colleges were not rivals. Students often moved between them to help the ministers, who had other duties.

John McMillan, the most important founder, came to the area in 1775. He built his log cabin school in 1780 near his church in Chartiers. He taught both college-level and elementary students. The first cabin burned down but was rebuilt by McMillan in the late 1780s. This log school is still preserved today. It is located next to the Middle School in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Thaddeus Dod built his log cabin school in Lower Ten Mile in 1781. He taught math, ancient languages, and classic subjects. Joseph Smith taught classical studies in his college, called "The Study" at Buffalo.

Washington Academy: A New School

Reverend McMillan and two church elders, Judge James Allison and Judge John McDowell, worked hard to get Washington Academy started. The Pennsylvania General Assembly officially approved it on September 24, 1787. The goal was to educate young people in "useful arts, sciences and literature." These three men, along with Reverends Dod and Smith, were among the first leaders. The board quickly got a large piece of land north of the Ohio River. This land was later sold to raise money for the academy.

After a difficult search, Thaddeus Dod was chosen as headmaster. He was known as the best scholar in western Pennsylvania. Classes began on April 1, 1789, in the upper room of the log courthouse in Washington.

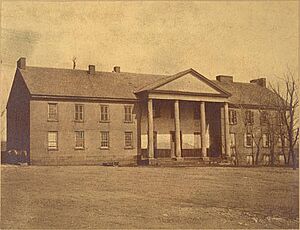

In 1790, a courthouse fire left the academy without a home. Due to money problems and the Whiskey Rebellion, the academy had no classes from 1791 to 1796. The leaders continued to meet. In 1792, the academy got four lots of land. A building was constructed there, with the foundation and walls finished in 1793. This building still exists today as McMillan Hall. It is one of the oldest academic buildings in continuous use in the nation.

Some early leaders of the academy were on different sides of the Whiskey Rebellion. Reverend McMillan supported the government. David Bradford, a leader of the rebellion, had other academy leaders on his side. Parts of Bradford's militia even camped on a hillside that later became part of the college campus.

The academy reopened in late spring 1796. It received a $3,000 donation from the General Assembly. This money was used to teach 10 poor students for two years. In 1805, Matthew Brown became the Principal and pastor of the First Presbyterian Church. He brought his student David Elliott to be a teacher. This gave the academy new energy.

Canonsburg Academy: A College is Born

In October 1791, Reverend Joseph Smith pushed for a school to train Presbyterian ministers. Several locations were considered. In October 1792, after a year's delay, McMillan was chosen as headmaster. Canonsburg was selected as the location for the "Canonsburg Academy." Col. John Canon donated land and paid for a two-story stone schoolhouse. Other funds were raised from local residents. McMillan later moved his students from his log cabin school to Canonsburg Academy. Canonsburg Academy was officially approved by the General Assembly on March 11, 1794. This made it stronger than Washington Academy.

In 1796, Canonsburg leaders began asking the General Assembly to make the academy the first college beyond the Allegheny Mountains. They asked for funds in 1798. While the academy was founded to train ministers, its requests to the state focused on its general education programs. Another request in 1798 highlighted its low tuition and existing buildings. In 1800, the General Assembly gave the academy $1,000. Finally, on January 15, 1802, with McMillan leading the board, the General Assembly granted a charter for "a college at Canonsburgh."

Jefferson College: Growth and Challenges

Starting Up and "The College War"

On April 29, 1802, Jefferson College was officially started. It was named after Thomas Jefferson, who sent a thank-you letter and a portrait as a gift. John McMillan was the first president of the board. For the first 25 years, McMillan held almost every job at the college. On August 29, 1802, John Watson, McMillan's son-in-law, became the first President of Jefferson College. After Watson died, McMillan took over daily operations. In April 1803, James Dunlap became president. He was well-liked and guided the college through tough times, including its growing rivalry with Washington College.

Jefferson College also had a preparatory department, now called Jefferson Academy. It prepared students for college by teaching Greek, Latin, writing, and math. In 1807, Washington College suggested that the two schools try to unite. This attempt failed because they couldn't agree on a location. Dunlap resigned in 1811. He was replaced by 23-year-old minister Andrew Wylie. Wylie expanded the subjects taught, adding chemistry.

Wylie supported joining with Washington College, as long as it benefited Jefferson. On October 25, 1815, committees from both colleges met and agreed on a plan to unite. The plan said the college would be in Washington. Most of the leaders and teachers would come from Jefferson. However, by 1817, the deal fell apart due to misunderstandings and accusations from alumni and supporters. This caused Jefferson to cancel the union. The bad feelings from this event were called "The College War." Because of this, Wylie resigned, and John McMillan again took over daily operations at Jefferson College.

William McMillan, John McMillan's nephew, became president on September 24, 1817. He was strict but not well-liked by students. He struggled with the college's problems. In 1922, five students were accused of causing "rebellion" by criticizing the Principal. These students had signed a petition saying McMillan was a poor teacher. The leaders decided not to pursue the matter, and McMillan resigned. This event showed a shift towards the college becoming less focused on strict religious authority.

Good Times Under Matthew Brown

In 1822, Matthew Brown was asked to leave Washington College. Some families there were uncomfortable with his growing influence. Brown had accepted a job at another college. But Rev. Samuel Ralston, who led Jefferson's board, convinced him to become President of Jefferson College instead. Brown's time at Jefferson College was very successful. The college graduated three times more students than before. His strong leadership, which had caused problems at Washington College, was well received in Canonsburg. Providence Hall was finished in 1832, providing much-needed space.

By this time, Western Pennsylvania was no longer the frontier. The National Road, which went through Washington, connected the area to eastern colleges. Jefferson College also began to attract many students from the South. In 1830, the college bought a farm where students could work to earn money for tuition. By 1832, 26 students were supporting themselves this way. The farm was sold in 1846. In 1832, the college started a scholarship system. Donors could give money to pay for a student's tuition. This system eventually caused big financial problems for the college.

Jefferson Medical College: A Separate Path

In the early 1800s, there were attempts to create a second medical school in Philadelphia. In 1824, a group of Philadelphia doctors asked Jefferson College to start a medical department in Philadelphia. The college agreed, creating the Medical Department of Jefferson College. In 1826, the Pennsylvania General Assembly approved this new department. It allowed the department to grant medical degrees. Ten additional Jefferson College leaders were appointed to oversee the new facility in Philadelphia.

The first class graduated in 1826. Classes were held in the Tivola Theater in Philadelphia. This theater had the first medical clinic attached to a medical school. Jefferson College allowed 10 of its graduates each year to attend the Medical College for free. Classes focused on practical medical training. In 1828, the Medical Department moved to the Ely Building. This building had a large lecture space and a 700-seat amphitheater for students to watch surgeries. It also had a hospital, which was only the second such medical school/hospital setup in the nation.

Jefferson College considered graduates of the Medical Department to be alumni. The connection with Jefferson College lasted until 1838. At that time, the Medical Department received its own separate charter. It began operating independently as the Jefferson Medical College. This medical college later grew into Thomas Jefferson University, a large health sciences university.

Challenges Before the Union

Robert Jefferson Breckinridge became President of Jefferson College in 1845. He was a religious preacher and a good speaker. He understood the growing number of Southern students, and the student body grew under his leadership. He resigned in 1847 due to health issues.

Alexander Blaine Brown, son of Matthew Brown, became the next president. Students had asked for a famous scholar, but Brown's election was well received. He had been a popular professor at Jefferson. His time was generally successful, with 50 to 60 graduates each year. The Synod of Pittsburgh offered to oversee Jefferson. But the college leaders declined. They did not want to give control of the college to any single religious group.

The Institution has always been mostly Presbyterian. It was founded in an area that was almost entirely Presbyterian. It has always depended mainly on Presbyterian support. It is expected to stay this way. However, its Presbyterianism has never been exclusive or biased. At least three parts of the large Presbyterian family, all holding "the like precious faith" have always worked together to support it. For one of these groups, which is the majority, to take full control of an institution that others are equally interested in, would be a serious breaking of trust and Christian kindness.

—Trustees of Jefferson College, Responding to Synod of Pittsburgh's offer to supervise Jefferson College

On January 7, 1847, Joseph Alden became President of Jefferson College. He was a well-liked teacher. The college's enrollment and money levels were high at first. But the growing conflict between the North and South prevented many Southern students from continuing their studies. This caused the number of graduates to fall. In 1860, the board finally stopped selling "perpetual scholarships." This program had greatly hurt the college's finances. By the end of his time, Jefferson College was in serious trouble. His successor, David Hunter Riddle, had the task of making the union with Washington College happen.

Former Jefferson College Buildings

The old Jefferson College buildings in Canonsburg were later used for an academy.

Washington College: Its Own Path

Starting and Early Years

In 1806, Matthew Brown and Parker Campbell successfully asked the Pennsylvania General Assembly to grant Washington Academy a college charter. It was only because of the hard work of Brown and David Elliott that the charter was issued. This was especially difficult because Jefferson College was so close by. The charter was granted on March 28, 1806. John Anderson, who had led Thaddeus Dod's log school, was one of the new board members.

During Brown's time as President, the connection between the college and First Presbyterian Church was strong. He led both organizations. However, his holding two powerful positions caused conflict with some important families in the community. This controversy, along with the stress of "The College War," led him to resign from the college. He decided to focus on his church duties.

"The College War" and What Happened Next

In 1817, the college and town faced difficult times without strong leaders. They asked Matthew Brown to return, but he declined. Andrew Wylie, who had been Matthew Brown's rival at Jefferson College, was named President of Washington College. He hoped to become pastor at the church, but many of Brown's supporters opposed him. During his successful time at Washington College, two wings were added to the Academy Building in 1818. He also secured a state grant to keep the college running. The National Road extended to Washington, making the town grow and become more connected.

In 1827, the college agreed to grant medical degrees to graduates of the Washington Medical College in Baltimore, Maryland. Washington College did not play a strong role in developing this medical school. Wylie left the college in 1828, tired of the conflicts. He followed the advice of his friend, William Holmes McGuffey, and went west to become the first president of Indiana University.

After Wylie left, Washington College had no president. The church had no pastor, and the long-time head of the board had died. In 1830, there was no graduation, and the college was in danger of closing. David Elliott, who was pastor at the church, agreed to take the president position temporarily. Elliott revived the college. He got money from the state, rebuilt the teaching staff, added English literature, and increased the student body from 20 to 120.

He was able to resign when David McConaughy was elected president in 1831. McConaughy was a respected scholar and public figure. During his time, the college added teachers and began building the New College. However, the college desperately needed money. It used risky financial practices, including a scholarship program that was even more dangerous than Jefferson College's. These practices were not sustainable and would eventually lead to ruin.

The last pieces of college land in Beaver County were sold in 1835. In 1843, Jefferson College suggested regular meetings with Washington. That year, both colleges agreed to raise tuition to $15.00 per month. In September 1847, this relationship became official. The tensions between the two colleges eased. Washington College even gave Jefferson's president, Alexander Blaine Brown, an honorary degree in 1847.

In 1850, James Clark became president. He was dedicated to traditional education. He resigned when it became clear that the college would accept an offer from the Synod of Wheeling to take control of the college's affairs. This move was meant to stabilize the college's finances. During this difficult time, with declining money and the shift to religious control, David Elliott, Samuel J. Wilson, and Brownson kept the college going. James I. Brownson, who led the board, took the presidency temporarily to help with the transition.

Challenges Before the Union with Jefferson College

Presbyterian minister John W. Scott became president in 1852. This was the same year the college became connected with the Synod of Wheeling. The Synod agreed to provide a $60,000 endowment to keep the college financially stable. In return, they had the right to nominate teachers and appoint leaders. To raise the endowment, a new scholarship plan was created. A family could buy tuition for one son for $50, for all sons for $100, and a permanent scholarship for $200. This plan quickly raised the money. However, it was even riskier than earlier plans, as the cost of education grew much faster than the money generated.

Scott successfully led the college through this transition without becoming too focused on one religious group. No students were denied admission or teachers denied jobs based on their religion. However, students began to show rebellious attitudes about the new required religious classes. Scott once criticized the students for their "picky way of attending church."

This period was also difficult for the nation, with growing tensions between the North and South leading to the Civil War. John W. Scott and many board members were strong abolitionists (against slavery). This was a big contrast to Jefferson College, which had many Southern students.

Washington & Jefferson College: A New Chapter

The Union: Two Become One

By 1865, Jefferson College and Washington College realized that joining together was their only way to survive. Both schools faced increased competition from eastern colleges. The Civil War had also taken many of their students to battle. People were also tired of supporting two very similar schools so close to each other. Earlier attempts to unite had failed because they couldn't agree on a location. Washington supporters pointed to its location on the National Road and its status as a commercial center. Canonsburg supporters highlighted its history with John McMillan.

On November 6, 1863, Dr. Charles Clinton Beatty offered $50,000 to encourage the schools to unite. The debate among the college boards continued for a while. Then, a meeting of alumni from both schools in Pittsburgh in September 1864 pushed for action. The alumni decided that joining was best for both schools. They agreed the new name should be Washington & Jefferson College. They also decided it should be non-religious but Protestant. The alumni plan suggested choosing the final location by drawing lots. The losing town would get the preparatory and science departments.

The Pennsylvania General Assembly granted a charter to the unified college on March 4, 1865. The final details of the union were a bit different from the alumni plan. The campus in Canonsburg would house the President, some professors, and older classes. The campus in Washington would house freshmen, the Vice President, and other professors. Board meetings and graduation would switch between the two locations. The new charter clearly stated that Washington & Jefferson College would not be tied to one specific religious group. On August 1, 1865, former Jefferson president Robert Jefferson Breckinridge was asked to be president. He declined due to his health and the impact of Abraham Lincoln's assassination. The union of the two colleges, one that attracted Southern students and one that was strongly against slavery, happened just as the United States was reuniting after the Civil War.

Challenges with Two Campuses

Jonathan Edwards became the first president of Washington & Jefferson College on April 4, 1866. He immediately faced big challenges. It was hard to manage a college across two campuses. There were also old prejudices and hard feelings among those loyal to Jefferson College or Washington College. Plus, many students were Civil War veterans from both sides.

The college also faced serious money problems. The charter required that money be split between the two campuses. This left both campuses short on funds. In April 1868, Edwards declared the two-campus plan a failure. He recommended that the school be combined into one location. On January 19, 1869, the leaders voted to combine the campuses. They left the final location open to Washington, Canonsburg, or anywhere else in the state. Many towns offered to host the college. The board narrowed the options to Canonsburg and Washington. Washington offered a $50,000 donation. On April 20, 1869, the board finally voted to place the college in Washington. Edwards resigned on the same day.

This outcome was a huge disappointment for Canonsburg and the Jefferson Alumni. The bitter feeling of regret in Canonsburg, and among the Jefferson alumni, over losing the college, was only slightly eased by the immediate plan to create an academy in the college buildings. This speaks clearly about the loyalty of that community and alumni to their college. It even makes it hard to criticize their words and actions, which for some time slowed the progress of the new college.

—Samuel McCormick, College Centennial, 1902.

United on One Campus

The first term of the unified campus began in September 1869. Samuel J. Wilson, a Washington College graduate, was appointed temporary president. However, operations were interrupted by a lawsuit. A group from Canonsburg and Jefferson College supporters argued that closing the Canonsburg campus broke the charter. On January 3, 1870, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that the board's action was legal. This decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. The final decision came in December 1871, again ruling that the consolidation was appropriate. The class of 1870 had only 10 students. The two groups of literary societies were merged, which helped smooth over hard feelings. Even though Jefferson College closed, its preparatory department continued to operate.

In 1870, George P. Hays became the second president of Washington & Jefferson College. As a Jefferson College graduate and Canonsburg native, he understood the local situation. The college was weak when he arrived, with only 75 students. He expanded the science department to a four-year program. The $50,000 donation from Washington was used to improve Old Main. By the time he left in 1881, about 185 students were attending classes, and the college's finances were becoming stable.

Moffat: A Time of Growth

James D. Moffat became the third president of Washington & Jefferson College on November 16, 1881. During his time, the college grew a lot. The number of professors tripled, and new campus buildings were constructed. In 1884, the college bought land for what is now Cameron Stadium. The students agreed to pay one dollar each term to help with the purchase. The college built a new gymnasium (now the Old Gym) in 1893. Hays Hall was finished in 1903. Thompson Memorial Library opened in 1905, and the Thistle Physics Building was completed in 1912. In 1893, the campus got an electric lighting system. In 1892, the board allowed the senior class to graduate in caps and gowns, starting a tradition. In 1910, Moffat refused a very large $40,000 donation. He believed the donor's family needed the money more than the college. Moffat personally paid for renovations to McMillan Hall in 1912. Moffat resigned on January 1, 1915, after 33 years of service.

In 1912, the Washington & Jefferson Academy was closed.

World War I and Beyond

Hinitt became president on September 23, 1914. His time as president was greatly affected by the United States entering World War I. Total college enrollment dropped by 50% to 180 students. The graduation ceremony in 1918 was held early to help men who were going to fight in Europe. Only 24 students could attend. Hinitt's speech that year reflected this: "To the Class of 1918, divided on this day, with so many of your men absent in service, I have but this word to say: Fear God and serve your country!" He resigned on June 30, 1918.

William E. Slemmons served as temporary president from May 1918 to June 1919. He was a college leader for 38 years and taught at W&J.

Samuel Charles Black was elected president on April 18, 1919. By spring 1920, the college had its largest enrollment ever, with 368 freshmen. Black took leave in summer 1921 to get married. While on his honeymoon, he became sick and died on July 25, 1921.

Simon Strousse Baker served as acting president after Dr. Black's death. He was elected president on January 26, 1922. During his time, the college buildings were greatly renovated and updated. Modern business methods were adopted, and the college's money grew a lot. There were also improvements in academics. Baker was well-liked by the college's leaders and many townspeople. However, the students felt Baker was "bossy" and "unfriendly." Students specifically disliked his rules about campus clothing and sports. Baker said it was a misunderstanding. Still, the students held a strike and walked out on March 18, 1931. Baker had hoped to finish building projects before retiring. But because of the strike, he resigned on April 23, 1931, for health reasons and "for the good of the College."

The Great Depression and World War II

After Baker resigned, Ralph Cooper Hutchison was elected president on November 13, 1931. At 34 years old, he was one of the youngest college presidents in the country. After the difficult time with President Baker, Time magazine noted that Hutchinson "pleased nearly everyone." In his first speech, Hutchinson spoke against the idea of going to college "because it pays." He encouraged students to value old-fashioned college education, which was "inviting only to those who did not set profit or wealth as their main objectives in life."

To make the college's science department stronger, Hutchison expanded the southern part of the campus. This included building the Jesse W. Lazear Chemistry Building. The main seminary building was bought, renovated, and renamed McIlvaine Hall. The John L. Stewart Memorial bell tower was added to McIlvaine Hall. The college built two buildings, Washington Hall and Jefferson Hall, for war-related projects. The Old Gym housed the Army Administration School, where hundreds of soldiers received training. The Reed residence was bought for use as a dormitory. The old Seminary dormitory was torn down to create more open space. Finally, the campus entrance was changed to face East Maiden Street. This allowed tourists on U.S. Route 40 to see the college. The expanded campus was dedicated on October 26, 1940. In 1943, Hutchison was appointed Director of Civilian Defense for Pennsylvania during the war. He also led the Pennsylvania United War Fund Program. President Hutchison resigned on May 7, 1945.

Post-War Growth and New Developments

James Herbert Case, Jr. became president on May 4, 1946. In fall 1946, the college had its largest student body ever, with 1047 students. 75% of these students were veterans of World War II. This large number of students required new construction. This included an expansion of Old Main for more food service space. The college added an Engineering Division. In October 1949, the college dedicated Mellon and Upperclass Dormitories. In June 1949, Case took a one-year leave to study problems of small colleges. In March 1950, he resigned to become president of Bard College.

In 1950, Boyd Crumrine Patterson became president. He oversaw changes to the curriculum and updated admissions standards. He also improved Washington and Jefferson's reputation. During Patterson's time, 17 buildings were constructed. These included the Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity House, the Wilbur F. Henry Memorial Physical Education Center, 10 Greek housing units, the U. Grant Miller Library, the Student Center, the Commons, and two new dormitories. The athletic fields were also improved. In 1952, the college's two war surplus barracks, Washington Hall and Jefferson Hall, were taken down. During his presidency, the college's money grew from $2.3 million to nearly $11 million.

Becoming Co-Ed and Continued Development

On December 12, 1969, the college leaders approved admitting women as undergraduate students. This change took effect in September 1970. Dr. Patterson retired on June 30, 1970.

Howard J. Burnett became president on July 1, 1970. That year, W&J admitted its first female students. It also hired its first female teachers and a woman as Associate Dean of Student Personnel. The school adopted a new academic calendar that included an intersession. To celebrate the 200th anniversary of W&J's founding, Burnett led the "Bicentennial Development Program." This resulted in three new buildings on campus: the Dieter-Porter Life Sciences Building, the Olin Fine Arts Center, and the Rossin Campus Center. During Burnett's time, the college acquired and renovated the W & J Alumni House. It also restored Thompson Memorial and McMillan Halls, added more dorms, and opened the Student Resource Center. The college expanded its academic programs. Student enrollment grew from 830 in 1970 to 1,100 in 1998.

In the early 1990s, the college was used as a setting for two movies. George A. Romero's film, The Dark Half, was filmed on W&J's campus in 1990. Students and teachers acted as extras. In 1993, Roommates was also filmed on campus. Burnett retired as president on June 30, 1998.

New Buildings and Community Connections

When Brian C. Mitchell became president in 1998, he faced a long-standing disagreement between the city of Washington, Pennsylvania and the college. Local officials blamed the college for many problems. In 2000, the college worked with other schools on a national project. This project aimed to create partnerships between colleges and local communities. Soon after, Washington & Jefferson received a $50,000 grant. This grant was used to develop a plan called the "Blueprint for Collaboration." This plan detailed goals for the college and city to work together on economic development, environmental protection, and historic preservation. The plan included offering more academic opportunities for the community. It also explored moving the college bookstore downtown and developing student housing there. The City of Washington began a downtown revitalization project.

Mitchell also expanded the college's academic programs. These included an Environmental Studies Program and a Music degree. The college's international partnership with the University of Cologne was expanded. A fundraising campaign brought in over $90 million. The college also received more applications and became more selective in its admissions. In June 2001, Mitchell and the college leaders adopted a new master plan. This plan aimed to remodel the campus and its learning environment. It included building modifications and a campus beautification program. The campus dining facility, the "Commons," was remodeled in 2000. The football field was improved and renamed Cameron Stadium in 2001. The Old Gym was repurposed as a fitness and wellness center. Several new buildings were constructed. These included The Burnett Center in 2001, a new technology center in 2003, and a new dormitory in 2002. A second dormitory was started in 2003 and finished after Mitchell left in March 2004 to become president of Bucknell University.

In 2008, the college created the Combat Stress Intervention Program. This was a research project funded by the U.S. Department of Defense.