History of the Canadian dollar facts for kids

Canada has a long and interesting story when it comes to its money. Before Europeans arrived, Indigenous peoples in Canada used things like wampum (special shell beads) and furs for trading. This continued even when they started trading with Europeans.

Wampum and beaver pelts (animal skins) were like money. When the French settled in Canada, they brought coins. They also created one of the first paper currencies by a Western government! Later, under British rule, more coins and paper money (banknotes) were introduced.

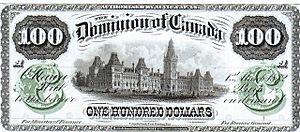

Over time, Canadian colonies slowly stopped using the British pound. Instead, they started using money that was linked to the United States dollar. When Canada became a country in 1867 (this is called Confederation), the Canadian dollar was officially created. By the mid-1900s, the Bank of Canada became the only place that printed paper money. Other banks stopped printing their own banknotes.

Canada started making its own coins soon after Confederation. In the 20th century, Canada has made many special commemorative coins. These temporary coins often replaced regular coin designs. There's also a long history of special collector coins, called numismatic coins.

Contents

First Peoples and Early Trade

The first people in Canada were the First Nations and Inuit. They traded goods by bartering, which means swapping items directly. Different things were used as money, like copper, wampum, and beaver pelts.

Wampum belts were made from many tiny shells. Indigenous peoples in eastern Canada used them to show wealth and as gifts. Wampum belts were also used as money when Europeans first arrived. They were even accepted as legal money in early Dutch and British colonies.

Indigenous peoples also traded furs with European traders. They exchanged furs for things like weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco. For a long time, during the North American fur trade, beaver pelts were accepted by everyone as a way to pay for things. Beaver pelts, called "Made Beavers," were even used as a way to count value by the Hudson's Bay Company. This helped them set fair prices for all their trade goods.

The Ojibwe people in eastern Canada were known for mining and trading copper. Special copper objects, like shields, had great economic and social value. The Haidas on the west coast used copper shields to show their status and wealth.

New France: 1608–1763

Why Coins Were Always Short

When Quebec was founded in 1608, French settlement and trade began. Early French settlers traded goods and used French coins. The smallest coin was the denier (penny). Twelve deniers made a sol or sou. Twenty sols made a livre of New France.

However, there was a big problem: there were never enough coins! Even though the French government sent silver coins from France, merchants often took them out of circulation. They used these coins to pay taxes, buy European goods, or simply kept them for safety.

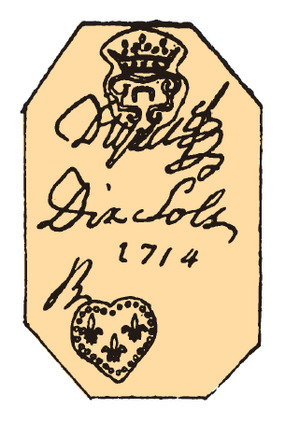

To fix this, the French government allowed special coins to be used only in New France. These coins were worth more than coins used in France. But they didn't work well because they had no value outside the colony. Sometimes, Spanish-American coins from Mexico, like the piastre, would secretly arrive. The government would stamp these coins with a fleur-de-lys (a French symbol) and a Roman numeral to show their value. Then, these stamped coins could be used.

Playing Card Money

By 1685, the coin shortage was so bad that colonial leaders started using playing cards as money!

The first playing card money was issued by Intendant Jacques de Meulles. In 1685, he needed to pay soldiers but had no funds. So, he made three kinds of playing card money (worth 15 sols, 40 sols, and 4 livres). The cards were marked on the back with the amount. Soldiers received them as payment and could exchange them for real coins three months later.

Even though they were just promises to pay, these playing cards started to be used like regular money. This was the first time a Western government issued paper money! The French government didn't like this idea. They worried the cards could be easily copied. But even when more coins arrived, the cards were still used. The Intendant issued more card money in later years. The Governor, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, eventually saw the value of this paper money. But over time, using card money led to prices going up (inflation). In 1717, the government took all card money out of circulation. They bought the cards back at half their value and burned them.

Taking away the card money didn't solve the coin shortage. In 1722, the government tried copper coins, but people didn't like them. The lack of coins caused a slowdown in the economy.

In 1729, the coin shortage was still a problem. So, card money was brought back, this time with France's approval. The amount of new card money was carefully controlled at first. It could be exchanged for bills in France. This meant fewer coins needed to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. Even though it was called "card money," these new notes were made from plain card stock, not actual playing cards. The government also issued "ordonnances de paiement" (payment orders) that acted like money.

However, France's money problems grew, especially with the costs of the Seven Years' War with Britain. This led to a huge increase in paper money in the 1750s. Prices went up quickly (inflation). People started to hide their real coins because they didn't trust the paper money. The paper money lost value, especially when France stopped promising to exchange it for coins until after the war.

French Coins

The French government kept sending coins to the colonies in the 1700s, like the gold Louis d'or.

Even though they were scarce, French coins were still used in the 1700s. These included 15- and 30-denier coins. These gold coins, called mousquetaires, were meant to pay soldiers and government workers. But they didn't stay in circulation for long. The name might have come from the cross on the back of the coins, which looked like the crosses on the cloaks of the famous musketeers.

Another coin used was the sol (sou). The sol was about the size of a modern one-cent coin. It was made between 1738 and 1756 and was worth 12 deniers. The double sol was made until 1764, though large shipments to Quebec and Cape Breton stopped in 1756. The double sol was worth 24 deniers.

End of French Rule

French rule ended when the British conquered Quebec in 1760. The value of the card money and ordonnances de paiement crashed. Their value came from France's promise to exchange them for coins, and that promise was now broken.

Under the Treaty of Paris, 1763, France agreed to still pay for the paper money. Three years later, they issued government bonds to replace the paper money. But France's finances were bad, and by 1771, these bonds were almost worthless. After New France fell, the card money and payment orders were only paid back at one-quarter of their original value. This made the people of Quebec deeply distrust paper paper money for many years.

British Colonial Rule: 1760–1825

Still Not Enough Money

The shortage of money continued under British rule. Many different foreign coins and paper notes from merchants were used for buying and selling. This caused a lot of confusion. Imagine buying vegetables for six pence and paying with a £1 note. You might get ninety-three different items back as change! This could include eight paper notes from different merchants, one silver coin, and eighty-four copper coins.

Colonial governments sometimes got creative with foreign money. For example, in 1808, officials in Prince Edward Island punched out the centers of Spanish-American dollars. This created the "holey dollar". Both the outer ring and the center piece were used as coins, worth one shilling and five shillings each.

Different Ways to Value Money

Because so many different types of money were used, two things were needed to keep track: "units of account" and "ratings" systems. People generally agreed to keep all their financial records in one currency. Other coins and bills were then converted to that system for bookkeeping. This needed a common conversion system, or "rating," usually based on the weight and value of the metal in the coins.

At first, all colonies used the British system of "Pounds, shillings, and pence" for accounting. But how they valued other currencies varied. Each colonial government created its own rating system for the many foreign currencies.

The two most important rating systems were the Halifax rating and the York rating. The Halifax rating said a Spanish dollar was worth five shillings. This was actually six pence higher than the Spanish dollar's real value at the time. The higher value was chosen to encourage people to keep using Spanish dollars and not melt them down for their metal. The Halifax rating started in Nova Scotia in 1749 and was made official in 1758. Even though the British government didn't approve, the Halifax rating was widely used in the Maritime colonies and later in Lower Canada.

The York rating was named after New York, where it was first used. The York rating valued a Spanish dollar at eight shillings. This system was brought to Upper Canada by United Empire Loyalists. Even though Upper Canada officially adopted the Halifax rating in 1796, the York rating continued to be used until Upper and Lower Canada joined to form the Province of Canada in 1841.

Government Bills

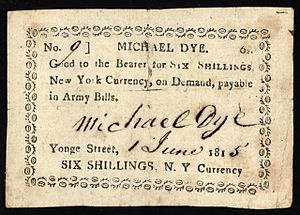

Colonial governments also started trying out paper treasury bills, often to pay for government costs. Prince Edward Island was the first Canadian colony to do this. In 1790, its government issued £500 in treasury notes. New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island all issued treasury bills in the early 1800s.

During the War of 1812, the British Army issued "Army bills." These could be exchanged for government bills in London. Eventually, £1.5 million worth were issued. All these bills were exchanged for currency by 1816, which helped people trust government paper money more.

The Colony of British Columbia also issued paper money in the 1850s, first in pounds and then in dollars.

Trade Tokens

Besides printing banknotes, some banks and merchants started making trade tokens. These tokens weren't official money, but they were accepted locally. Most tokens were imported from England. Banks in Lower Canada worked together to make their tokens more reliable. One token they made had the Montreal coat of arms on one side and a picture of a habitant (French-Canadian farmer) on the other. These tokens were nicknamed "Papineaus" after Louis-Joseph Papineau, a leader of the 1837 rebellion in Lower Canada. He was known for wearing habitant clothing. Today, these are known as Habitant tokens.

The two main fur-trading companies, the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company, also issued trade tokens. These were used in their large trading networks. The Hudson's Bay Company tokens were based on the "Made beaver" pelts, which had been used as a way to trade.

From British Pound to Canadian Dollar: 1825–1867

In the mid-1800s, there was a disagreement between Britain and its colonies. Britain wanted all colonies to keep using British money (sterling) to make trade easier within the Empire. But the Canadian colonies, both in the east and British Columbia, increasingly wanted their money linked to the US dollar. This was because they traded a lot with the nearby United States. Eventually, local trade won out, and Canadian colonies switched to currencies linked to the US dollar.

During this time, laws set fixed exchange rates for coins. These rates were often based on how much precious metal (like gold or silver) the coins contained.

British Order of 1825

The issue first came up in 1825. The British government passed an order to encourage using British money throughout the British Empire, including Canada. But this order actually had the opposite effect in Canada. It made the few British coins that were circulating disappear. This happened because the value set for a Spanish dollar (four shillings and four pence sterling) wasn't fair compared to the gold in a British gold sovereign coin. When Britain tried to fix this in 1838, the British North American colonies were left out because of recent rebellions.

Colonial Pounds

Each colony had its own money system. Even though they were based on the British system of pounds-shillings-pence, the exact value of each currency could be different, depending on the colony's laws. There was the Canadian pound (used in Upper and Lower Canada), the New Brunswick pound, the Newfoundland pound, the Nova Scotian pound, and the Prince Edward Island pound. All of these were slowly replaced with decimal systems (like dollars and cents) that were linked to the US and Spanish dollars.

Province of Canada Pound, 1841

After Upper and Lower Canada joined, the Province of Canada adopted a new system based on the Halifax rating. New laws set exchange rates for a new Canadian pound. One Canadian pound, four shillings, and four pence was equal to one pound sterling (British pound). This meant the new Canadian pound was worth about sixteen shillings and five pence sterling.

The law also set the value of the new Canadian pound against the US dollar. The American gold eagle coin was set at two pounds, ten shillings Canadian (meaning the Canadian pound was worth four US dollars). The law also set exchange rates for the Canadian pound against the French franc, old Spanish, Mexican, and Chilean doubloons, and other Latin American currencies. British money, US gold and silver coins, and Spanish dollars were all considered legal money.

Moving Towards the Dollar and Decimal Money

Throughout the 1850s, the British and colonial governments discussed money. The British government wanted all colonies to use money based on sterling. This could be British money or local colonial money tied to sterling, including a decimal system. But colonial governments increasingly preferred a decimal money system based on the United States dollar. This was more practical because they traded so much with the United States.

In June 1851, representatives from the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia met in Toronto. They talked about creating a shared decimal currency. London agreed to a decimal system but hoped the colonies would use a sterling unit called 'Royal'.

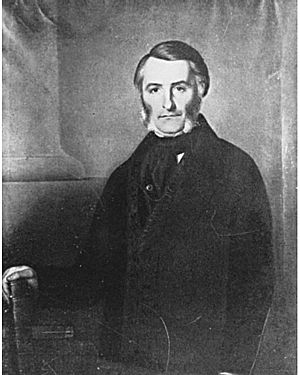

Province of Canada

After the 1851 meeting, the government of the Province of Canada, led by Co-Premier Francis Hincks, started moving towards decimal money. The provincial Parliament passed a law to introduce a pound sterling unit along with decimal coins. The idea was that the smaller coin values would match exact fractions of the US dollar. The law hoped that this decimal money could "...hereafter be advantageously made common to all the Provinces of British North America, as being simple and convenient in itself, and well calculated to facilitate their commercial intercourse with other parts of this continent" (meaning, make trade easier). London delayed the law for technical reasons. Another law passed at the same time kept the official exchange rates for British and US money used in Canada.

As a compromise between using sterling or the US dollar, the Province of Canada passed a law in 1853 to introduce the gold standard. This meant money's value was tied to both the British gold sovereign and the American gold eagle coins. The gold sovereign was legal money at a value of £1 equal to $4.8666 Canadian. The $10 eagle was worth $10 Canadian. No new coins were made under the 1853 law. British sterling coins became legal money, and all other silver coins were officially removed from circulation, though they were still used. Dollar transactions became legal. Since New Brunswick and Canada had the same conversion rates, their currencies now matched, fixed at the same value as the US dollar.

The move towards decimal money continued. In 1857, the Province of Canada decided that all government accounts would be kept in dollars and cents. The next year, 1858, the first Canadian decimal coins were released. They were made at the Royal Mint in London and said "Canada" on them, with a picture (effigy) of Queen Victoria. The coins came in one-cent, five-cents, ten-cents, twenty-cents, and fifty-cents.

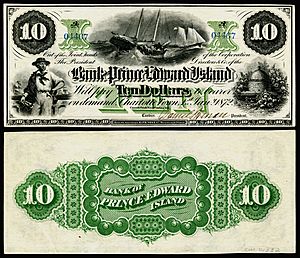

New Brunswick

In 1852, New Brunswick passed a law similar to Canada's. It set "pounds, shillings, and pence" as the government's accounting unit. But it also made both British and US coins legal money. The law also allowed the provincial government to get new coins. New Brunswick ordered coins from the Royal Mint in London in 1860. But because the Mint was so busy, the first New Brunswick coins didn't arrive until 1862.

Nova Scotia

In 1860, Nova Scotia adopted a decimal system. It set the exchange rates for British money and other coins. The government was allowed to get coins in cents, and government accounts would be in dollars and cents. All court decisions would also be in dollars and cents. However, Nova Scotia's law set the exchange rate as £1 equal to $5. This meant Nova Scotia's system didn't quite match Canada's and New Brunswick's, which gave a slightly lower value to the pound. Nova Scotia also ordered coins from the Royal Mint in 1860, but like New Brunswick, their first coins didn't arrive until 1862.

Newfoundland

Before 1865, Newfoundland used the Newfoundland pound, which was worth the same as the British pound sterling. In 1865, Newfoundland switched to a decimal system, the Newfoundland dollar. It started making its own coins: one-cent, five-cent, ten-cent, twenty-cent, and two-dollar coins. The Newfoundland decimal coins were based on fractions of the Spanish dollar used in British Guiana. This made one British penny exactly equal to two new Newfoundland cents. This was a compromise for those who wanted British money and those who wanted US money. However, it meant the Newfoundland dollar was worth slightly more than the Canadian dollar (about 1.014 Canadian dollars). So, Newfoundland and Canadian money weren't easily interchangeable.

Even though Newfoundland's government issued coins, it let two private banks print banknotes: the Union Bank and the Commercial Bank. By the late 1800s, both banks were poorly managed and in weak financial shape. When the cod fishing industry had a downturn, both banks failed on Monday, December 10, 1894. This day became known as Black Monday. Both banks closed forever that day, and their notes became worthless. This caused a financial crisis on the island. The Government of Newfoundland passed a law promising to pay for the failed banks' notes, but at a lower value. The government also made a law to set the Newfoundland dollar's value the same as the Canadian dollar. Canadian banks quickly moved in after the crash. The result was that Newfoundland's money system became part of Canada's.

British Columbia

In 1867, the Colony of British Columbia passed a law to use decimal money based on the United States dollar. The law said all government accounts would be kept in dollars and cents. It also set exchange rates for the various coins being used, at £1 equal to $4.85. This law replaced similar ones made a few years earlier by the former colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia before they joined together.

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island switched to decimal money in 1871. The dollar replaced the Prince Edward Island pound. By law, dollars and cents became the way the colonial government kept its accounts. The law also set the exchange rate between British sterling and the dollar at £1 equal to $4.8666. The colonial government was allowed to arrange for printing notes in dollars and issuing copper coins in cents.

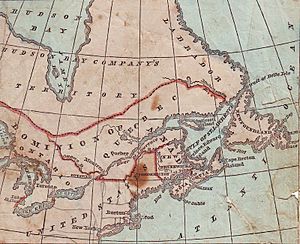

Canada Becomes a Country, 1867

Canada was created in 1867 by the British North America Act, 1867. It started as a federation with four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. The federal Parliament was given full control over "Coins and Currency," as well as "Banking, Incorporation of Banks, and the Issue of Paper Money." This led to big changes in the new country's money system, with control over coins and banknotes becoming centralized in Ottawa.

Money Laws

In 1868, the federal Parliament passed the first Currency Act. It allowed for Canada's dollar to eventually have the exact same value as the United States dollar. But for a while, the money values from before Confederation stayed the same. The dollars used in Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick kept their value. The Nova Scotia dollars kept their higher value in Nova Scotia.

This continued for three more years until Parliament passed the Uniform Currency Act. This law made Nova Scotia use the same dollar as the rest of Canada, based on the pre-Confederation dollar. The dollar's value was still set by comparing it to the British sovereign and the American eagle. The rate was 4.8666 Canadian dollars equal to £1, and ten Canadian dollars equal to the ten-dollar American eagle. These were the same rates set in the 1853 Province of Canada law.

The Uniform Currency Act automatically applied to Manitoba when it joined Canada. But it didn't apply to British Columbia and Prince Edward Island right away. In 1881, Parliament passed another law extending the Uniform Currency Act to those two provinces.

First Canadian Coins

In 1867, the federal government planned to issue its own coins. These would be in denominations of one cent, five cents, ten cents, twenty-five cents, and fifty cents. The coins were similar to those of the Province of Canada. The main difference was that the twenty-five-cent coin replaced the twenty-cent coin. The twenty-cent coin had never been popular because Canadians were used to the US twenty-five-cent coin, which was widely used. The new Canadian coins didn't actually start circulating until they arrived from the Royal Mint in London in 1870. The government didn't issue the one-cent coin until 1876, because there were still so many old pennies from before Confederation.

One problem the government faced was the large amount of US and British silver coins circulating in Ontario and Quebec. The issue was that these coins were "over-rated." Their face values were higher than the actual value of the silver they contained. Banks would only accept them at a discount, but farmers and merchants had to take them at their full value. This difference hurt farmers and merchants. It also pushed the government's one-dollar and two-dollar notes out of circulation.

The solution was to collect these US and British coins and send them back to their home countries. Also, it was decided that in the future, their official value would be fixed at only 80% of their face value. Francis Hincks, who was back as the federal Minister of Finance, worked with bankers to successfully send these silver coins back to the United States and Britain.

There was a similar problem with copper coins. Before Confederation, many different copper coins were used. These included pennies from provincial governments, US and British coppers, low-value tokens from private banks or merchants, and sometimes even brass buttons! Working with the banks, the federal government slowly removed all the old pre-Confederation and foreign pennies from circulation. In 1876, the Canadian one-cent coin was finally issued.