History of the Federal Reserve System facts for kids

The United States Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913. Think of it as the country's main bank, helping to keep the economy stable and healthy.

Contents

Early Central Banks in the U.S.

The Federal Reserve System is actually the third central banking system in U.S. history. Before it, there were two other banks:

- The First Bank of the United States (1791–1811)

- The Second Bank of the United States (1817–1836)

Both of these banks lasted for 20 years. They printed money, gave out loans, and handled the government's money. The U.S. government owned 20% of these banks. This meant that wealthy investors owned most of them. Many people, especially state banks, didn't like these large banks. They felt these banks had too much power.

President Andrew Jackson strongly opposed the Second Bank. He believed it was a monopoly that hurt ordinary people. In 1832, he said that such a bank took money from the American people. Because of his actions, the Second Bank's charter was not renewed in 1837. This led to a period called "free banking," where many different banks operated without a strong central one.

In 1863, during the American Civil War, a new system of national banks was created. This was done to help pay for the war. These banks could print their own money, but it was based on U.S. government bonds they held. This system was later called the National Banking Act. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency was created to oversee these banks. This office still exists today and checks on all nationally chartered banks.

Why the Federal Reserve Was Created in 1913

The national bank currency had a problem: it wasn't flexible enough. If the value of government bonds went down, banks had to reduce the amount of money they had. This meant they couldn't give out new loans or had to ask for old loans back.

Also, banks had to keep their extra money (reserves) in larger city banks. During busy times, like planting season for farmers, rural banks would use up their reserves. If people heard a bank was having money problems, they would rush to take out their money. This often led to financial panics, where many banks failed. The U.S. economy faced several such panics in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Studying Banking Problems: The National Monetary Commission

After a very bad financial crisis in 1907, people realized something had to change. In 1908, Congress created the National Monetary Commission. Its job was to study banking and currency and suggest reforms.

The leader of this commission was Senator Nelson Aldrich. He was a financial expert. Aldrich sent groups to study banking systems in other countries, especially in Europe. He started out against a central bank. But after seeing Germany's system, he changed his mind. He began to believe a central bank was a good idea.

However, many politicians were suspicious of a central bank. They thought Aldrich might be biased because he was connected to rich bankers like J.P. Morgan.

In 1910, Aldrich and several powerful bankers met secretly at Jekyll Island, Georgia. These bankers included Frank A. Vanderlip (from National City Bank), Henry Davison (from J.P. Morgan Company), and Charles D. Norton (from First National Bank of New York). Paul Warburg of Kuhn, Loeb, & Co. led the discussions. They worked together to create a plan for a new banking system.

Frank Vanderlip later wrote that this secret meeting was where the idea for the Federal Reserve System truly began. He said they had to keep it secret because if the public knew that a group of bankers wrote the bill, Congress would never pass it. The importance of this secret meeting was revealed to the public a few years later by a journalist.

The Aldrich Plan and Its Opposition

The plan that came out of the Jekyll Island meeting was called the "Aldrich Plan." It suggested creating one big central bank called the National Reserve Association. This bank would have 15 branches across the country. It would print money, hold bank reserves, and manage interest rates.

Most Republicans and Wall Street bankers liked the Aldrich Plan. But it didn't have enough support in Congress to pass. Many people, especially in the South and West, thought the plan would give too much power to wealthy families and large corporations.

A famous politician named William Jennings Bryan said that "Big financiers are back of the Aldrich currency scheme." He believed that if it passed, big bankers would "be in complete control of everything."

Some Republicans also opposed the plan. Senator Robert M. La Follette and Representative Charles Lindbergh Sr. argued that the plan favored Wall Street. Lindbergh called it the "Wall Street Plan" and a "scheme plainly in the interest of the Trust."

Because of these concerns, a special group in Congress, called the Pujo Committee, investigated the idea of a "Money Trust." They found that a small group of powerful people on Wall Street controlled much of America's money and credit. Their report said that this concentration of power was dangerous.

Passing the Federal Reserve Act in 1913

The Democratic Party opposed the Aldrich Plan. However, they also wanted to fix the banking system to prevent financial panics. When Woodrow Wilson became president in 1912, he was determined to reform banking.

Wilson believed the Aldrich Plan had some good ideas. But he insisted that the new central bank must have a Federal Reserve Board appointed by the president. This would give the government more control over the bankers.

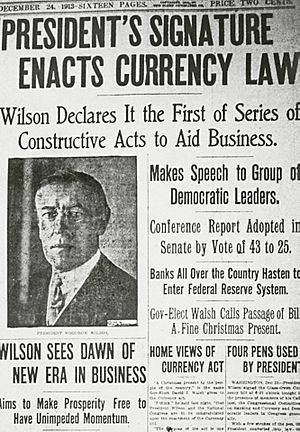

After many discussions and changes, the Federal Reserve Act finally passed Congress in December 1913. Most Democrats supported it, while most Republicans were against it.

Even though the Aldrich Plan was not passed under its original name, many of its main ideas were included in the final Federal Reserve Act. Frank Vanderlip, one of the bankers at Jekyll Island, later wrote that the "essential points" of the Aldrich Plan were in the law that was passed.

Some critics, like Representative Charles Lindbergh Sr., still worried. He said that the new Federal Reserve Board would not control interest rates. He believed Wall Street would still control the money, just in a different way.

To get the bill passed, President Wilson needed the support of William Jennings Bryan, a very popular politician. Bryan and his supporters wanted a government-owned central bank that could print money when Congress needed it. They worried the new plan gave bankers too much power. Wilson convinced them that because the new money would be government money, and the president would appoint the board members, it met their needs.

The new system was designed with 12 regional banks. This was meant to prevent too much power from being concentrated in New York. However, in practice, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York became the most important of these banks.

When President Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on December 23, 1913, he felt he had helped create something that would greatly benefit the country.

How the Federal Reserve Operated (1915-1951)

The Federal Reserve System began operating in 1915. It played a big role in helping to pay for World War I. The Fed offered low interest rates to banks that bought government bonds. This increased the money supply, but it also caused prices to rise (inflation).

After the war, the U.S. economy grew. In the 1920s, the New York Fed used its power to buy government securities to help the economy. But in 1928, as a stock market bubble grew, the Fed raised interest rates.

Then came The Great Depression in 1929. The stock market crashed, and the economy suffered greatly. Many banks failed. The Federal Reserve did not take much action to stop the collapse. One expert said the Fed "more or less let the banking system collapse."

In response to the Great Depression, Congress passed new laws. The Glass-Steagall Act in 1933 created the FDIC, which insures bank deposits. This means people's money in banks is protected, so they are less likely to rush and take it all out during a panic. The Banking Act of 1935 created the Federal Open Market Committee, which is a key part of the Fed today.

After World War II, the Employment Act of 1946 added a new goal for the Fed: to help the country achieve maximum employment.

The Fed Becomes More Independent (1951)

During World War II, the Federal Reserve promised to keep interest rates very low to help the government borrow money for the war. It continued this policy even after the war, which led to rising prices.

In 1951, the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury Department made an agreement called the 1951 Accord. This agreement gave the Federal Reserve more independence. It meant the Fed could make its own decisions about interest rates without being pressured by the government to keep them low for borrowing. This was a big step in making the Fed the independent central bank it is today.

In 1956, the Bank Holding Company Act made the Fed responsible for regulating companies that own more than one bank.

The Fed in Modern Times

In 1978, a law called the Humphrey-Hawkins Act required the head of the Federal Reserve to report to Congress regularly. This helps keep the Fed accountable.

In 1979, Paul Volcker became the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. At that time, inflation was very high. Volcker took strong action, making money harder to get. By 1986, inflation had dropped a lot.

In 2001, the U.S. economy faced a recession. From 2001 to 2003, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates many times to try and boost the economy. In 2006, Ben Bernanke became the chairman.

The 2008 Financial Crisis

In 2007, a problem with home loans led to a big financial crisis. The Federal Reserve started cutting interest rates to help the economy. In January 2008, the Fed made a large emergency cut to its main interest rate to try and stop a big drop in the stock market.

In 2009, Barack Obama nominated Ben Bernanke for a second term as chairman. In 2013, Janet Yellen was nominated to take over.

In December 2015, after nine years, the Fed raised its main interest rate slightly. This was a sign that the economy was getting stronger.

Important Laws Affecting the Federal Reserve

Here are some key laws that have shaped the Federal Reserve:

- Banking Act of 1935

- Employment Act of 1946

- Federal Reserve-Treasury Department Accord of 1951

- Bank Holding Company Act of 1956

- Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act (1978)

- Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980)

- Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (1999)

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |