History of the Franco-Americans facts for kids

The Franco-Americans, also called French Americans, are people in the United States whose families came from France or French Canada. This includes people from Quebec (called Québécois) and Acadia.

Today, about 11.8 million Franco-Americans live in the U.S. Around 1.6 million of them speak French at home. Another 450,000 Americans speak a French-based language like Haitian Creole. Even though many Franco-Americans live in the U.S., they are sometimes less noticed than other large groups. This is partly because they live in many different places, and many have blended into American culture.

Contents

Early Franco-American Settlers

Franco-Americans were never part of the Franco-American alliance. This was an agreement between King Louis XVI of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War.

First European Settlers

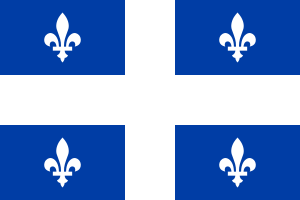

Most Franco-Americans today come from settlers who lived in Canada in the 1600s. Back then, Canada was known as New France. Later, it became the Province of Quebec. Many Franco-Americans in New England and the Midwest are from the Quebec Diaspora. This means their families moved from Quebec. Not as many Franco-Americans are from Acadia, a region in Canada's Maritime provinces.

What's special about these early Franco-Americans is that they arrived before the United States was even a country. They founded many towns and cities. They were some of the first Europeans to settle in what is now the U.S. Major settlement areas for them included the Midwest and Louisiana. Today, you can find Franco-Americans mostly in New England, northern New York, the Midwest, and Louisiana. There are three main types of French-Americans: French Canadian, Cajun, and Louisiana Creole.

French Louisiana History

From 1534 to 1763, France explored and claimed lands in the Americas. They divided their lands into five areas: Canada, Acadia, Hudson Bay, Newfoundland, and Louisiana. In 1713, the The Treaty of Utrecht made France give up its claims to mainland Acadia, Hudson Bay, and Newfoundland to Great Britain.

By 1679, French Louisiana was a large area of New France. French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle named it after King Louis XIV. It was under French control from 1682 to 1762, and again from 1802 to 1804. This huge territory included most of the land drained by the Mississippi River. It stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. It also went from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. Louisiana was split into Upper Louisiana (north of the Arkansas River) and Lower Louisiana. The U.S. state of Louisiana today is named after this historical region. But it is only a small part of the original French territory.

French explorers began exploring this area during King Louis XIV's rule. French Louisiana did not grow much because France lacked people and money. After losing the Seven Years' War in 1763, France had to give up the eastern part of Louisiana to the British. The western parts went to Spain. This ended direct French control. However, Louisiana became a safe place for Acadians who were forced to leave their homes. These people became known as the Cajuns.

France got the western territory back in a secret agreement in 1800. But Napoleon Bonaparte needed money for wars in Europe. So, he decided to sell the territory to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This ended France's presence in Louisiana.

French Protestants in the Thirteen Colonies

In 1562, French naval officer Jean Ribault sailed to the New World. He founded Fort Caroline, which is now Jacksonville, Florida. This fort was a safe place for Huguenots, who were French Protestants. In 1565, the Spanish attacked the fort and killed Ribault and many of his followers.

The French government stopped Huguenots from starting colonies in New France. So, a group led by Jessé de Forest sailed to North America. They settled in the Dutch colony of New Netherland. This area later became parts of New York and New Jersey. They also settled in some British colonies, including Nova Scotia. Many important families in New Amsterdam were Huguenots. In 1628, the Huguenots started their own church called L'Église française à la Nouvelle-Amsterdam.

When they arrived in New Amsterdam, Huguenots received land across from the Manhattan settlers. They also settled near Newtown Creek. They were the first Europeans to live in Brooklyn, in an area then called Boschwick. Today, this neighborhood is known as Bushwick.

Later Franco-Americans

The Quebec Diaspora

The Quebec diaspora was a time when many people left Quebec. It was sometimes called the "great demographic hemorrhage." These Canadian immigrants moved across North America. They went to New England, New York State, the American Midwest, and parts of Ontario. Some also went to the Canadian Prairies.

This movement started around 1840. It was largest from the U.S. Civil War until the 1890s. It ended with the Great Depression in the 1930s. Historians like Gerard J. Brault and David Vermette have studied this part of Franco-American history.

Moving from Quebec to the United States

Historians have long discussed why so many people left Quebec for the United States. In the 1830s and 1840s, Quebec faced problems with wheat and potato crops. Also, the population grew, but there wasn't enough farmland for young people. The fur trade declined, and the lumber trade struggled in the 1840s. This meant fewer jobs. Even when times were good, not everyone benefited equally.

At the same time, French Canadians learned more about opportunities in America. They read about it in newspapers. Transportation and communication improved. Family and friends who had visited the U.S. also shared information. Despite efforts to stop people from leaving, about 900,000 French Canadians settled permanently in the U.S.

Vermont and New York were among the first places French Canadians moved to. People were settling there in the early 1800s. In the mid-1800s, many French Canadians moved to northeastern Illinois. They started communities like Bourbonnais and St. Anne. Michigan and Minnesota also became popular places to move.

In the Northeast, American factories offered many jobs. French-Canadian immigrants found work in textile mills and other industries. They moved to places like Cohoes in New York, Lewiston in Maine, Fall River and Lowell in Massachusetts, Woonsocket in Rhode Island, and Manchester in New Hampshire.

Life was hard, and work was tiring. Large factories often hired whole families, including children. At first, Franco-Americans were hesitant to join unions. But in the early 1900s, more and more joined to fight for better working conditions.

Challenges and Community

Franco-Americans faced challenges like nativism, which is being against immigrants. They also dealt with tensions between different ethnic groups. Some people called them "the Chinese of the Eastern States." French-Canadian migrants strongly protested this. They refused to be treated as a different race. They also faced hateful words from some newspapers and groups like the American Protective Association. In the 1920s, they sometimes faced the Ku Klux Klan, which wanted white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant control.

To protect their culture, migrants created their own Roman Catholic churches and schools. They also formed social groups and started newspapers. They celebrated Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, often with big parades, around June 24. Canadian business leaders and priests helped lead these efforts.

Keeping their French-Canadian culture was not always easy. They sometimes argued with the Irish community. This happened when French Canadians wanted to leave existing churches to form their own "national" churches. These churches would recognize their unique culture. If an Irish priest was assigned to one of these new churches, the local people resisted. The idea of survivance meant that speaking French would help French Canadians stay Catholic. Having their own churches would also help keep their traditions from Quebec alive.

Franco-Americans were important in the industrial economy. They were also known for their arguments with the Irish during strikes and church issues. Their yearly parades and their presence as characters in stories and movies made them visible. This visibility sometimes caused anti-immigrant feelings. But it also helped them in politics.

Many Franco-Americans became local officials and state lawmakers. They served as mayors in cities like Woonsocket, Lewiston, and Manchester. In the early 1900s, Aram Pothier and Emery San Souci became governors of Rhode Island. Felix Hebert was elected to the U.S. Senate.

Franco-Americans have made many important contributions. These include in the arts (Lucien Gosselin), entertainment (Frank Fontaine, Robert Goulet, Triple H, Rudy Vallée), and industry (the Aubuchon family, Yvon Chouinard, Joe Coulombe). They also contributed to literature (Will Durant, Jack Kerouac, Annie Proulx), law (Robert Desty, E.J. Dionne), religion (Charles Chiniquy, Louis Edward Gelineau), sports (Joan Benoit, Leo Durocher, Nap LaJoie), and new inventions (John Garand, Cyprien Odilon Mailloux).

Newspapers

French-Canadian immigrants started many French-language newspapers. The first was the Patriote canadien, started in Burlington in the 1830s. Most of these papers lasted only a few years. But some, like L'Etoile (Lowell) and Le Messager (Lewiston), served their communities for many decades.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |