History of the Puritans from 1649 facts for kids

Puritans were a group of Protestant Christians in England who wanted to make the Church of England simpler and more "pure." They believed the church still had too many practices similar to the Catholic Church. From 1649 to 1660, during a time called the Commonwealth of England, Puritans had a lot of power because they were allied with the government led by Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell was a powerful leader, known as the Lord Protector, until he passed away in 1658.

During this period, Puritans split into many different groups. The largest group was the Presbyterians, who had many clergy members. However, Cromwell often favored another group called the Independents. After the king returned to power in 1660, many Puritan ministers were forced out of the Church of England. This changed the Puritan movement, leading to the formation of separate Presbyterian and Congregational churches. These groups were known as Dissenters because they did not agree with the official church.

Contents

England's Changing Times (1649–1660)

Religious Freedom and New Ideas (1649–1654)

The time from 1649 to 1660, known as the English Interregnum, was a period of great religious change in England. When the Commonwealth of England was formed in 1649, Oliver Cromwell and his supporters took control. Cromwell believed in religious freedom for many groups.

In 1650, the government removed a law that made everyone attend services in the official church. This meant that even though England had an official church with a Presbyterian system, people were not legally required to go to its services.

Before this, in 1646, the English Parliament had already changed the Church of England. They removed bishops and replaced them with a Presbyterian system. They also wanted to replace the traditional prayer book with a new guide for worship. However, these changes were slow to happen for a few reasons:

- In many areas, especially where people supported the king, bishops and the old prayer book were still popular. Many ministers and their church members simply continued their usual worship.

- Independent groups did not like the new system and started forming their own churches.

- Some clergy who liked the Presbyterian idea still disliked parts of the new law. This made them less eager to put the new system into practice.

- Since bishops were gone, there was no one to make sure the new Presbyterian system was followed. So, with people opposing it and others not caring, little was actually done.

When the law requiring church attendance was removed, religious differences became even more open. While Presbyterians were technically in charge of the official church, other groups were free to worship as they wished. Groups like the Baptists, who used to meet in secret, could now worship openly. Other ministers, who preferred the Congregationalist way of organizing churches, also started their own groups outside the official church.

Many new sects (religious groups) also formed during this time. These groups often focused less on the Bible and more on direct experiences with the Holy Spirit. Some of these groups included the Ranters, the Fifth Monarchists, the Seekers, the Muggletonians, and the Quakers. The Quakers became a very important and lasting group.

From 1660 to Today

Puritans and the King's Return (1660)

The largest group of Puritans, the Presbyterians, were not happy with the state of the church under Cromwell. They wanted to bring back religious order across England. They believed that only restoring the king could achieve this and control the many new religious sects. Because of this, most Presbyterians supported the return of Charles II to the throne.

Charles II's most loyal supporters, who had been with him in exile, wanted to bring back bishops to the Church of England. However, in April 1660, Charles II promised that while he would restore the Church of England, he would also allow some religious toleration for those who did not belong to it.

Charles II appointed William Juxon, an old bishop, as the head of the Church of England. It was understood that Gilbert Sheldon would likely take over later. As a sign of goodwill, a leading Presbyterian, Edward Reynolds, was made a bishop and a chaplain to the king.

Soon after Charles II returned, in early 1661, some radical groups like the Fifth Monarchists tried to overthrow him. This created a lot of fear about another Puritan uprising.

Charles II still hoped to change the official prayer book in a way that most Presbyterians would accept. This would allow more Puritans to stay within the Church of England. In April 1661, a meeting called the Savoy Conference was held. Twelve bishops and twelve Presbyterian leaders met to discuss changes to the prayer book. However, most of the Presbyterian ideas were rejected.

When a new Parliament, called the Cavalier Parliament, met in May 1661, their first action was to pass the Corporation Act 1661. This law prevented anyone who had not recently taken communion in the Church of England from holding public office in cities. It also required officeholders to swear loyalty to the king and reject certain Puritan beliefs.

The Great Ejection (1662)

In 1662, the Cavalier Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity 1662. This law brought back the Book of Common Prayer as the only official way to worship in the Church of England. The Act said that any minister who refused to follow the new prayer book by August 24, 1662, would be removed from the Church of England. This day became known as Black Bartholomew's Day among those who disagreed with the church. It was a sad day for them, similar to a massacre that happened in 1572.

Most ministers who had served in Cromwell's church did agree to follow the new prayer book. These ministers were often called Latitudinarians. They later formed a part of the Church of England that was more open-minded. The Puritan movement had already been divided, and this decision made it even more so.

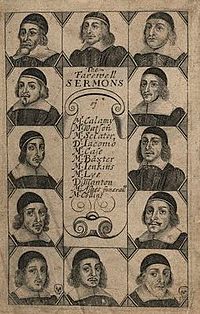

About two thousand Puritan ministers chose to resign from their church positions rather than follow the new rules. Important figures like Richard Baxter and Edmund Calamy the Elder were among them. After 1662, the term "Puritan" was generally replaced by "Nonconformist" or "Dissenter" to describe these Puritans who refused to conform.

Challenges for Dissenters (1662–1672)

Even though they were removed from their churches in 1662, many non-conforming ministers continued to preach. They met with their followers in private homes and other places. These secret meetings were called conventicles. The groups formed around these ministers became the start of the English Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Baptist churches we know today.

The Cavalier Parliament was very unhappy about these continued meetings. In 1664, they passed the Conventicle Act 1664, which banned religious gatherings of more than five people outside the Church of England. In 1665, they passed the Five Mile Act 1665. This law stopped ejected ministers from living within five miles of their old church, unless they promised never to oppose the king or try to change the government or church.

Under these strict laws, known as the Clarendon Code, many ministers were put in prison in the late 1660s. One famous person who was imprisoned during this time was John Bunyan, a Baptist writer, who was in jail from 1660 to 1672.

At the same time, some government and church leaders tried to find a way for some dissenting ministers to return to the Church of England. These plans would have created a divide between Presbyterians and Independents. However, the discussions never worked out, and it became impossible for Dissenters to rejoin the official church.

The Path to Religious Freedom (1672–1689)

In 1670, King Charles II secretly agreed with the King of France to allow more religious freedom for Catholics in England. In March 1672, Charles issued his Royal Declaration of Indulgence. This declaration stopped the harsh laws against Dissenters and made it easier for Catholics to practice their faith privately. Many Dissenters, including John Bunyan, were released from prison because of this.

However, the Cavalier Parliament strongly opposed the King's declaration. Supporters of the Church of England did not like the easing of the laws. Many people across the country also worried that Charles II was secretly planning to bring Catholicism back to England. The Parliament's strong opposition forced Charles to withdraw his declaration, and the strict laws were put back into effect. In 1673, Parliament passed the first Test Act. This law required all public officeholders in England to reject a Catholic belief, making sure no Catholics could hold office.

Later Developments

The experiences of Puritans influenced later religious movements within the Church of England, such as the Latitudinarian and Evangelical trends. In the 1690s, the differences between Presbyterian and Congregationalist groups in London became clearer, leading to a lasting split.

In the United States, the Puritan settlements in New England had a major impact on American Protestantism. However, with the start of the English Civil War in 1642, fewer Puritans moved to New England. This was because Puritans had more power and influence in England during this time, so they felt less need to leave.

Many people who moved to New England looking for religious freedom found the Puritan system there to be too strict. Examples include Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, and Mary Dyer. Despite this, Puritan populations in New England continued to grow, with many large and successful families.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |