Houston Stewart Chamberlain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Houston Stewart Chamberlain

|

|

|---|---|

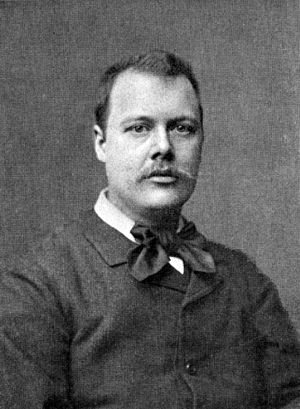

Chamberlain in 1895

|

|

| Born | 9 September 1855 Southsea, Hampshire, England

|

| Died | 9 January 1927 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | British, German |

| Spouse(s) |

Anna Horst

(m. 1878; div. 1905)Eva von Bülow-Wagner

(m. 1908–1927) |

| Parent(s) | William Charles Chamberlain (1818–1878) Eliza Jane Hall (–1856) |

| Relatives | Basil Hall Chamberlain (brother) |

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (born September 9, 1855 – died January 9, 1927) was a British-German writer and thinker. He wrote books about political philosophy and natural science. He is best known for his ideas about different human groups and their roles in history.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Houston Stewart Chamberlain was born in Southsea, England. His father was a Rear Admiral in the British Navy. His mother passed away when he was very young, so his grandmother raised him in France. He had an older brother, Basil Hall Chamberlain, who became a professor in Japan.

Houston was often sick, so he spent winters in warmer places like Spain and Italy. Moving around a lot made it hard for him to make close friends.

School Days

Chamberlain started school in Versailles, France. His father wanted him to join the military. So, at age eleven, he went to Cheltenham College, a boarding school in England. Many students from this school became officers in the Army or Navy.

Chamberlain did not like Cheltenham College. He felt lonely and out of place there. He was more interested in art and nature than in military life. He was a "dreamer" who loved the outdoors.

His main interests at school were natural sciences, especially astronomy. He did not want to serve in the British Empire. Because of his poor health, he had to leave school at age fourteen. After this, he felt like he didn't belong in Britain. He later wrote that he had become "completely un-English."

He then traveled around Europe with a German tutor, Mr. Otto Kuntze. This tutor taught him German and sparked his interest in German culture and history. Chamberlain also learned Italian and loved Renaissance art.

University Studies

Chamberlain later studied at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. He focused on subjects like botany (the study of plants), geology (the study of Earth), and astronomy. He also studied the human body. In 1881, he earned a degree in physical and natural sciences.

Love for Germany

When Chamberlain was 23, he heard the music of Richard Wagner for the first time. It changed his life, feeling like a powerful discovery. He became a big fan of Wagner and developed a strong love for Germany. This love grew even more when he fell in love with a German woman named Anna Horst. His wealthy British family did not approve of her because she was not from a high social class. This made him feel even more distant from Britain.

Chamberlain moved to Dresden, Germany. There, he read many philosophical writings. During this time, he started to believe in völkisch ideas. This was a German movement that focused on a shared national identity, often linked to ideas about race and a connection to the land. From 1884, he began to include anti-Jewish and racist ideas in his letters.

In Dresden, Chamberlain also became interested in Hindu mythology. He learned Sanskrit to read ancient Indian texts like the Vedas. He saw the ancient Aryan heroes in these stories as strong and spiritual. He believed these Aryans were related to Germanic peoples. He thought modern Germans could learn from Hinduism. This is partly why the swastika, an ancient Indian symbol, became popular with some völkisch groups.

Life in Vienna

In 1889, Chamberlain moved to Austria. It was during this time that his ideas about different human groups and their characteristics became clearer.

In Vienna, Chamberlain became friends with other fans of Wagner's music. He also became close with Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, who was the German Ambassador to Austria-Hungary. Eulenburg shared Chamberlain's love for Wagner, and also his anti-Jewish and anti-British views.

The Foundations Book

In 1896, a publisher asked Chamberlain to write a book about the achievements of the 19th century. In October 1899, Chamberlain published his most famous book, Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, which means The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century.

The book sold very well. Within 10 years, 60,000 copies were sold. By the start of World War I, 100,000 copies were sold. By 1938, over a quarter of a million copies were sold. This success made Chamberlain a very famous writer.

The Foundations was a "racial history" of humanity. It claimed that all the great achievements of the 19th century came from the "Aryan race." Chamberlain planned to write two more volumes, but he never finished the third.

Chamberlain's Idea of Aryans

Chamberlain believed that many European peoples, like Germans, Celts, Slavs, Greeks, and Latins, belonged to the "Aryan race." He even included the Berber people from North Africa. He thought the Germanic peoples were the purest Aryans.

Chamberlain believed that everything good in the world came from Aryans. For example, he wrote that Jesus Christ was not Jewish, but Aryan. He also said that the great achievements of ancient Greece and Rome were due to Aryan blood. He saw ancient Greece as a perfect example that Germans could bring back.

Chamberlain presented the "Jewish race" as the opposite of the Aryans. He claimed that every good quality of the Aryans had an exact opposite negative quality in Jews.

Conspiracy Theories

In his book, Chamberlain claimed that "all the wars" in history were linked to "Jewish financial operations." He warned that Jews wanted to control all nations and the "whole earth." He also claimed that Jews wanted to create a world where only they were a "pure race," and everyone else would be a mixed group, "degenerate physically, mentally and morally."

Chamberlain also claimed that Jews founded the Roman Catholic Church. He said this church taught a "Judaized" form of Christianity that was not true Christianity. He believed that in the 16th century, German leaders like Martin Luther broke away from Rome's influence. This, he said, created a "Germanic Christianity."

Chamberlain thought that a dictatorship was the best type of government for Aryans. He blamed Jews for inventing democracy as a way to destroy Aryans. He also blamed capitalism on Jews, saying they created it to get rich at the expense of Aryans.

Chamberlain did not suggest a specific "solution" to the "Jewish Question" in his book. He left it to his readers to figure out what to do after reading his ideas.

Friendship with Kaiser Wilhelm II

In 1901, the German Emperor Wilhelm II read The Foundations and was very impressed. He believed that God had sent Chamberlain's book to the German people and Chamberlain himself to him.

Later that year, Chamberlain met the Kaiser through a mutual friend. They became very good friends and wrote letters to each other until Chamberlain's death. Chamberlain advised the Kaiser to create a "racially aware" and "centrally organised Germany" that would "rule the world."

Personal Life and Money

In 1906, Chamberlain and Anna Horst divorced.

Chamberlain earned money from his book sales and articles. He also received financial support from a wealthy German piano maker and a Swiss industrialist. This gave him a good income. In 1908, he married Eva von Bülow, the daughter of his hero, Richard Wagner. He was very happy to be part of the Wagner family.

Chamberlain's Personality

Chamberlain saw himself as a prophet. He wrote to the Kaiser, "Today, God relies only on the Germans." People who knew him described him as a quiet, charming, and polite man. He could talk brilliantly about many topics.

However, under this calm surface, Chamberlain had a very strong and sometimes extreme side. His notes and letters show that he was deeply paranoid. He believed he was the victim of a huge worldwide Jewish conspiracy to harm him. He often stayed at home because he feared that Jews were plotting to murder him.

World War I Writer

In August 1914, Chamberlain began to suffer from a gradual paralysis that affected his arms and legs. By the end of World War I, much of his body was paralyzed.

When World War I started in 1914, Chamberlain was still a British citizen by name. He tried to join the German Army, but he was too old (58) and too sick.

During the war, Chamberlain wrote several propaganda texts against his home country, Britain. In these writings, he claimed that Germany was a peaceful nation and that Britain's political system was fake. He said that Germany had true freedom and that German was the greatest language. He also believed the world would be better if it adopted German rule instead of British or French-style governments.

Chamberlain wanted Germany to win the war and take over much of Europe, Africa, and Asia. He believed this would give Germany the "world power status" it deserved. He worked with groups that supported these goals. He also signed a petition asking the government to win the war and annex as much land as possible. Much of his wartime writing also had strong anti-Jewish ideas. He claimed that German Jews were trying to stop Germany from winning the war.

Chamberlain also wanted big changes in German society. He wanted to create a "people's community" where everyone worked together for the nation. He called for an end to democracy and the creation of a pure dictatorship. He also wanted a new economic system that was a "third way" between capitalism and socialism. He believed this would be run by a small group of leaders who would manage the economy scientifically.

Chamberlain believed that Germany would win the war only if its people truly wanted victory. In the last two years of the war, he became focused on defeating what he called the "inner enemy" within Germany. He claimed that Germany was divided into "patriots" and "traitors." His wartime writings against this "inner enemy" were similar to the "stab-in-the-back legend" that appeared after 1918.

During the war, many Germans saw Britain as their main enemy. So, Chamberlain, as an Englishman who supported Germany, became even more famous. His wartime essays were very popular, selling about 1 million copies between 1914 and 1918.

Influence on Hitler

In November 1918, Chamberlain was devastated by Germany's defeat in the war and the fall of the monarchy. He was also completely paralyzed and believed it was due to poisoning by the British secret service.

Chamberlain began to admire Adolf Hitler, seeing him as "Germany's savior." Hitler had read Chamberlain's book The Foundations and his writings about Wagner. Hitler was greatly influenced by Chamberlain's ideas.

Both Chamberlain and Hitler were big fans of Wagner's music. This shared interest helped them become friends, along with their shared dislike of Jewish people.

In 1923, Chamberlain met Adolf Hitler in Bayreuth. He later joined the Nazi Party and wrote for its publications. The main Nazi newspaper praised him on his 70th birthday, calling The Foundations the "gospel of the National Socialist movement." In 1924, Chamberlain wrote an essay praising Hitler as a "man of genuine simplicity with a fascinating gaze."

Death

Chamberlain continued to live in Bayreuth until his death on January 9, 1927. His ashes were buried in the Bayreuth cemetery. Adolf Hitler was present at his funeral. His gravestone has a verse from the Gospel of Luke: "The Kingdom of God is within you."

Impact of The Foundations

During his lifetime, Chamberlain's books were widely read, especially in Germany. Many conservative leaders in Germany liked his ideas. Kaiser Wilhelm II supported Chamberlain. He wrote letters to him, invited him to his court, and made sure copies of The Foundations were in German libraries and schools.

The Foundations became a very important book for German nationalism. Its ideas about "Aryan" superiority and fighting against "Jewish" influence spread widely in Germany. While it didn't create the entire framework for later Nazi ideas, it certainly gave them a way to seem intellectual and justified.

Chamberlain lived to see his ideas start to become popular. Adolf Hitler visited him several times as he became a more important political figure in Germany. Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi Party members attended Chamberlain's funeral.

See also

In Spanish: Houston Stewart Chamberlain para niños

In Spanish: Houston Stewart Chamberlain para niños

- Oswald Mosley

- Wagner family tree

- William Patrick Stuart-Houston

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |