Hrant Dink facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hrant Dink

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 15 September 1954 Malatya, Turkey

|

| Died | 19 January 2007 (aged 52) Istanbul, Turkey

|

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Armenian |

| Citizenship | Turkish |

| Alma mater | Istanbul University |

| Occupation |

|

|

Notable credit(s)

|

Founder and editor-in-chief of Agos |

| Spouse(s) |

Rakel Yağbasan

(m. 1976) |

| Children | 3, including Arat |

Hrant Dink (Armenian: Հրանդ Տինք; 15 September 1954 – 19 January 2007) was an important Turkish-Armenian journalist. He was the main editor of Agos, a newspaper published in both Armenian and Turkish.

Dink was a well-known member of the Armenian community in Turkey. He worked hard to bring Turkish and Armenian people closer. He also spoke up for human and minority rights in Turkey. Dink often criticized Turkey's view on the Armenian genocide. He also questioned how the Armenian diaspora campaigned for its international recognition.

Because of his writings, Dink faced legal charges three times for "insulting Turkishness." He also received many threats from Turkish nationalists.

Sadly, Hrant Dink was killed in Istanbul on January 19, 2007. His killer was a 17-year-old Turkish nationalist named Ogün Samast. Dink was shot three times and died right away. Photos of the killer with smiling police officers caused a big scandal. Samast was later sentenced to 22 years in prison.

Over 100,000 people marched at Dink's funeral. They protested his death, chanting, "We are all Armenians" and "We are all Hrant Dink." His death led to more calls to change a law called Article 301. This law had been used to charge Dink.

Contents

Hrant Dink's Early Life

Hrant Dink was born in Malatya, Turkey, on September 15, 1954. He was the oldest of three sons. His father was a tailor and his mother was a homemaker. In 1960, his family moved to Istanbul for a new start.

A year later, his parents separated. Seven-year-old Hrant and his brothers had no home. Their grandmother enrolled them in the Gedikpaşa Armenian Orphanage. Dink often said his grandfather, who spoke seven languages, inspired his love for reading.

The Gedikpaşa Armenian Orphanage became Hrant Dink's home for ten years. In summers, the children stayed at the Tuzla Armenian Children's Camp. They helped build and improve the camp. This camp was very important to Dink. He met his future wife there as a child. The government closing the camp in 1984 made Dink more aware of Armenian community issues. This led him to become an activist.

Dink went to Armenian primary schools and high school. He also worked as a tutor. He later studied zoology at Istanbul University. During this time, he briefly changed his name to Fırat Dink. This was to separate his political activities from the Armenian community. He later started studying philosophy but did not finish that degree.

Meeting Rakel Yağbasan

Dink met his future wife, Rakel Yağbasan, at the Tuzla Armenian Children's Camp in 1968. She was nine years old. Rakel was born in 1959 in Silopi. She was one of 13 children.

Rakel's family, the Varto clan, had a unique history. In 1915, five families from the clan escaped to Mount Cudi. They lived there for 25 years without contact with the outside world. They later reconnected with society and mostly spoke Kurdish. However, they remembered their Armenian roots and Christian faith.

An Armenian Protestant preacher brought about 20 children from the clan, including Rakel, to the Tuzla Camp. Rakel learned Turkish and Armenian at the camp and orphanage. She finished primary school. She could not attend Armenian community schools because she was registered as a Turk. Her father did not allow her to attend Turkish schools past fifth grade. So, she was tutored privately at the orphanage.

Rakel's father first did not want her to marry Hrant Dink. Their clan usually married within their own group. But Armenian community leaders and Rakel herself convinced him. Hrant Dink and Rakel Yağbasan married at the Tuzla Camp on April 19, 1976. They were 22 and 17. A year later, they had a church wedding. They had three children: Delal, Arat, and Sera.

Dink's Religious Views

Hrant Dink was baptized and married in the Armenian Apostolic Church. However, he was educated and cared for in Armenian Protestant places. He saw both churches as part of his culture. He said he did not focus much on religious rituals. His funeral service was held in the Apostolic Church, with Protestant ministers also speaking.

After University Life

After university, Hrant Dink completed his military service in Denizli. He was not promoted to sergeant despite good scores. He felt this was unfair, possibly due to his Armenian background. This feeling of discrimination was a turning point for him to become an activist.

In 1979, Dink and his brothers opened a bookstore called "Beyaz Adam" (White Man) in Bakırköy. The store became popular and grew into a publishing house. It focused on textbooks, children's books, and dictionaries.

After the 1980 military coup, it became hard for Turkish citizens to get passports. Dink's brother used fake papers to travel and was caught. Hrant Dink was also taken into custody. He was questioned two more times by police. Once, when a former Tuzla Camp resident was investigated for links to an Armenian group. Another time, when Hrant Güzelyan, who ran the Tuzla Camp, was arrested.

Dink also played professional football for Taksim SK, an Armenian community team, in the 1982–83 season.

Tuzla Armenian Children's Camp Issues

Hrant Dink and his wife Rakel took over managing the Tuzla Armenian Children's Camp after Güzelyan's arrest. They also continued their bookstore business. In 1979, a court case started to take away the camp's ownership from the Gedikpaşa Armenian Protestant Church. This was based on a 1974 rule that limited property ownership for minority groups.

After a five-year legal fight, the court ruled against the church. In 1984, the camp was closed. The land was returned to its previous owner.

In 2001, the camp grounds were sold to a local businessman. He planned to build a house there. Dink contacted him and explained the land belonged to an orphanage. The businessman offered to donate the land back. But the law at the time did not allow it. When Dink died in 2007, the camp grounds were still empty.

Editor of Agos Newspaper

Dink helped start Agos weekly newspaper. It was the only newspaper in Turkey published in both Armenian and Turkish. He was its main editor from 1996 until his death in 2007. The first issue came out on April 5, 1996.

Agos was created after a meeting called by Patriarch Karekin II. Mainstream media had started linking Armenians in Turkey with the PKK. The Patriarch wanted to know what to do. The idea was that Armenians in Turkey needed to communicate with the wider society. This led to the creation of Agos.

Before Agos, Dink was not a professional journalist. He had written some articles for local Armenian papers. He also sent corrections and letters to national newspapers. He quickly became known for his writings in Agos. He also wrote columns for national newspapers like Zaman and BirGün.

Before Agos, the Armenian community had two main newspapers. Both were only in Armenian. By publishing in Turkish, Hrant Dink opened up communication for the Armenian community. After Agos started, Armenians became more involved in Turkey's political and cultural life. Public awareness of Armenian issues also grew. Hrant Dink became a well-known public figure in Turkey.

Agos started with 2,000 copies. By the time Dink died, it printed about 6,000 copies. It was very influential, even beyond its circulation. Agos became a newspaper whose opinions were highly valued.

Newspaper's Editorial Focus

Dink's unique view was like a "four-way mirror." He understood the feelings of Armenians living abroad, citizens of Armenia, Turkish Armenians, and citizens of Turkey. Under Dink's leadership, Agos focused on five main areas:

- Speaking out against unfair treatment of Armenians in Turkey.

- Reporting on human rights issues and democracy problems in Turkey.

- Sharing news about Armenia, especially Turkey-Armenia relations.

- Publishing articles on Armenian culture and its impact on the Ottoman Empire and Turkey.

- Criticizing problems and lack of openness in Armenian community groups.

As an activist, Dink often wrote about democracy issues in Turkey. He defended other writers who faced criticism for their views.

Dink acted as a voice for the Armenian community in Turkey. Through Agos, he addressed the unfairness and problems the community faced. Agos criticized discrimination against Armenians in Turkish media. It also shared problems faced by Armenian foundations. Dink spoke against the destruction of Armenian cultural heritage.

Views on Armenian Issues

Dink was one of Turkey's most important Armenian voices. He refused to be silent, even with threats to his life. He always said his goal was to improve relations between Turks and Armenians. He was a strong peace activist. In his speeches, he often used the word "genocide" when talking about the Armenian genocide. This term is strongly rejected by Turkey.

At the same time, he felt the term "genocide" had a political meaning, not just a historical one. He criticized Armenian groups abroad for pushing governments to officially recognize the genocide. In 2005, he said Germany was using the genocide to block Turkey from joining the European Union. He felt ashamed, as an Armenian, that such political games continued. He said he shared the pain of Turkish and Muslim families. He called this process yüzleşme, or Turkey facing its past.

Dink believed that Armenians living abroad should be free from the burden of historical memory. He thought they should focus on the needs of living people.

He believed that by fixing problems in how Turks and Armenians talked to each other, they could improve relations. This would benefit Turkish Armenians. He was against a French law that made denying the Armenian genocide a crime. He planned to go to France to break this law if it came into effect.

According to Dink, Agos helped the Armenian community grow. It tripled participation in Patriarchal elections. It trained many journalists and became the community's face to Turkish society. He wanted to create an "Institute of Armenian Studies" in Istanbul. He aimed for the newspaper to be a democratic voice for Turkey. It would inform the public about unfairness against the Armenian community. A main goal was to help dialogue between Turkish and Armenian communities.

Dink's Policy Views

Dink supported greater involvement of Turkish-Armenians in Turkish society. He criticized unfairness by the state. He often said that a stronger Turkey would come from ending discrimination. Even after being found guilty for speaking about the Armenian genocide, Dink valued his community and country. He often said his analysis and criticism aimed to strengthen Turkey. He focused on problems in community groups. He tried to gain rights through legal ways. He was always open to finding common ground. He once noted, "After all, Turkey is very reluctant to concede rights to its majority as well."

In one of his last talks, Dink said that Kurds were falling into the same traps Armenians did in the past. He stated that "English, Russian, German, and French are playing the same game again in this land." He said Armenians trusted them, thinking they would be saved from the Ottoman Empire. But they were wrong, because these countries left after their business was done. He claimed the US was doing the same thing now with the Kurds. He said, "That is America. Comes, minds its own business, and when he is done, leaves. And then people here, scuffle within themselves."

Facing Legal Charges

Dink was charged three times for "insulting Turkishness" under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code. He was found innocent the first time. The second time, he was found guilty and given a suspended 6-month jail sentence. He appealed this to the European Court of Human Rights. When he died, prosecutors were preparing charges for a third case.

The first charge came from a speech he gave in 2002. He was accused of insulting Turkishness and the Republic. On February 9, 2006, Dink was found innocent of these charges.

The second charge was for his article "Getting to know Armenia" (2004). In it, he suggested that Armenians living abroad should let go of their anger against Turks. He wrote, "replace the poisoned blood associated with the Turk, with fresh blood associated with Armenia." This led to a six-month suspended sentence.

A Turkish court rejected his appeal in May 2006. Dink then appealed to the European Court of Human Rights on January 15, 2007. His appeal argued that Article 301 limited freedom of speech. It also said Dink was discriminated against because he was Armenian.

In September 2006, another case was opened against Dink. This was also for "insulting Turkishness" under Article 301. Amnesty International said this was part of a pattern of bothering the journalist for expressing his views. Charges were also brought against Serkis Seropyan and Dink's son, Arat Dink. After Hrant Dink's death, the case against him was dropped. However, proceedings for Serkis Seropyan and Arat Dink continued.

In September 2010, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Turkey had violated Dink's freedom of speech. They said Turkey's actions against him were for criticizing the state's denial of the 1915 events as genocide.

Assassination of Hrant Dink

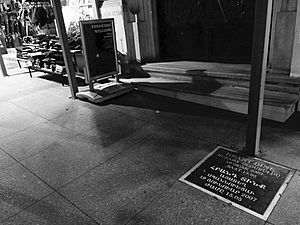

Hrant Dink was killed in Istanbul around noon on January 19, 2007. He was returning to the Agos newspaper office. The killer said he was a student who wanted to meet Dink. When he was turned away, he waited nearby. Witnesses said a man, about 25-30 years old, shot Dink three times in the head from behind. The killer then ran away. Police said the killer was 18-19 years old. The owner of a nearby restaurant said the killer looked about 20, wore jeans and a cap, and shouted "I shot the infidel" as he left. Dink's wife and daughter collapsed when they heard the news.

Dink's Funeral

Dink's funeral was held on January 23, 2007, at the Surp Asdvadzadzin Patriarchal Church in Istanbul. Over 100,000 people marched in protest of his assassination. They chanted "We are all Armenians" and "We are all Hrant Dink." Along the way, thousands of people threw flowers from their office windows.

The Trial and Aftermath

The trial for Dink's murder began in Istanbul on July 2, 2007. Eighteen people were charged. The main suspect, Ogün Samast, was under 18, so his hearing was not public.

On July 25, 2011, Samast was found guilty of planned murder and illegal gun possession. He was sentenced to 22 years and 10 months in prison. Another suspect, Yasin Hayal, was found guilty of ordering the murder and sentenced to life in prison.

In July 2014, Turkey's Supreme Court ruled that the investigation into the killing was faulty. This allowed for trials of police officials and other public authorities. In January 2017, Ali Fuat Yılmazer, a former police intelligence chief, said the killing was "deliberately not prevented." He stated that security authorities in Istanbul and Trabzon were responsible.

The trials continued for several years, involving 78 defendants. On March 26, 2021, the court gave its final verdict. Former police chiefs Yılmazer and Ramazan Akyürek received life sentences for planned murder. Twenty-six defendants were jailed for different periods. Others were found innocent or had their cases separated. An appeals court confirmed most of these rulings on May 5, 2022.

Dink's family said the verdicts "could not convince themselves nor the public." Their lawyer pointed out that several public officials involved in the murder were not even put on trial.

Dink v. Turkey Case

In 2011, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Turkey had failed to protect Hrant Dink's life and freedom of expression. He had received death threats after writing articles about Turkish-Armenian identity. He also wrote about the Armenian origins of one of Atatürk's adopted daughters. And he wrote about Turkey's role in the Armenian genocide during World War I.

Awards and Recognition

Hrant Dink received many awards for his work and bravery:

- 2005: Ayşenur Zarakolu Award for Freedom of Thought and Expression (Turkey)

- 2006: Henri Nannen Prize for Freedom of the Press (Germany)

- 2006: Oxfam/Novib PEN Award for Freedom of Expression (Netherlands)

- 2006: Bjørnson Prize (Norway)

- 2007: Armenian Presidential State Prize (posthumous). This was for his work on "restoring historical justice, understanding between peoples, freedom of speech, and human rights."

- 2007: Hermann Kesten Medal (posthumous). This was for his efforts to support writers who were being persecuted.

- 2007: International Press Institute World Press Freedom Hero (posthumous)

Taner Akçam's 2012 book The Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity is dedicated to Dink.

The Hrant Dink Foundation now holds an annual Hrant Dink Award ceremony. This award recognizes other human rights activists.

Legacy

See also

In Spanish: Hrant Dink para niños

In Spanish: Hrant Dink para niños

- Agos

- Anti-Armenianism

- Armenian genocide

- Armenian genocide denial

- Armenian genocide recognition

- List of journalists killed in Turkey

- Ararat (film) 2002 film about the Armenian genocide

- Conscience Films