Illustrating Middle-earth facts for kids

Since J. R. R. Tolkien wrote The Hobbit in 1937, many artists have tried to draw and paint the amazing world of Middle-earth. Tolkien himself was an artist! He liked the work of people like Pauline Baynes and Ted Nasmith. But he didn't like everyone's art, like Horus Engels's drawings for a German Hobbit book.

Tolkien had strong ideas about how his fantasy stories should be illustrated. Sometimes he didn't want any pictures at all. Other times, he drew his own pictures for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Some people say his ideas about art were a bit mixed up.

After Tolkien passed away in 1973, many more artists created pictures of Middle-earth. They used all sorts of styles, from Alexander Korotich's scratchboard art to Queen Margrethe II of Denmark's woodcut-style drawings. Peter Jackson's famous Lord of the Rings movies (2001–2003) and The Hobbit movies used art by John Howe and Alan Lee. Their pictures have really shaped how many people imagine Middle-earth today.

Contents

Tolkien's Own Artwork

J. R. R. Tolkien didn't just write about Middle-earth; he also drew and painted for his stories. He made many different kinds of art, like paintings, drawings, fancy writing (calligraphy), and maps.

Some of his artworks were put right into his books, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Others were used on the covers of his books, including The Silmarillion. After he died, collections of his art were published. Experts now study him as an artist, not just a writer.

Tolkien's Ideas About Illustrations

Tolkien had strong feelings about drawing pictures for fantasy stories, especially his own. But what he said at different times wasn't always easy to understand.

Why Pictures Might Limit Imagination

In 1936, Tolkien wrote that "illustrations do little good to fairy-stories." He thought that when an author describes things generally, it lets the reader use their own imagination. If an artist draws a very specific picture, it might stop the reader from imagining their own version.

For example, Tolkien's own drawings for The Hobbit gave readers a basic idea. But they still allowed readers to "paint their own mental pictures," guided by the story, but not stuck with one exact image.

When Pictures Could Work Well

The 1938 American version of The Hobbit had five of Tolkien's own watercolor paintings. At that time, Tolkien was okay with pictures in the book if they showed specific parts of the story.

In 1938, he wrote to his American publishers, Houghton Mifflin. He suggested they find an artist who could draw people well. He said his own drawings of hobbits were "very ill-drawn." He also mentioned that if Bilbo wore boots in a picture, it should be only when he was in Rivendell. Otherwise, Bilbo should have bare feet.

Pictures Must Match the Story

In 1946, Tolkien didn't like Horus Engels's drawings for a German Hobbit book. He said they were "too 'Disnified' for my taste."

Tolkien believed that good illustrations needed to match the story, even if the artist was famous. In 1948, when Allen & Unwin worked with Milein Cosman for Farmer Giles of Ham, Tolkien said her drawings looked like other famous artists' work. But he didn't care about "fashionableness." He said her art didn't "resemble their text." He also said the trees were badly drawn and the dragon was "absurd." He felt Cosman's pictures were "wholly out of keeping with the style or manner of the text."

By 1949, Allen & Unwin found another artist, Pauline Baynes, for Farmer Giles of Ham. Tolkien loved her work! He said her pictures were "more than illustrations, they are a collateral theme." This meant they were so good, his story felt like a description of her drawings.

Art Should Show Heroes

Tolkien met the Dutch artist Cor Blok in 1961. He liked five of Blok's paintings so much that he bought two of them. One, "Battle of the Hornburg II," hung in his front hall.

Tolkien told his publisher, Rayner Unwin, that Blok's paintings were "most attractive." He especially liked the Hornburg picture. He thought other works were "attractive as pictures but bad as illustrations." He wondered if any talented artist would "try to depict the noble and the heroic," which he felt were key parts of his work. Still, in 1962, Tolkien suggested Blok and Pauline Baynes to illustrate a special edition of The Lord of the Rings.

| A close-up of Cor Blok's painting Battle of the Hornburg II. Tolkien liked it so much he bought it. He felt it was the only one of Blok's Middle-earth pictures that worked as an illustration. |

Leave Room for Imagination

Tolkien told Blok that he wasn't "in favour of illustrated editions." However, they both agreed that an artist should only draw what's really important.

Tolkien also told Pauline Baynes that he had objections to illustrations. But he said that pictures could be good for "small things" or for "decoration." These comments show that Tolkien believed artists should still leave room for the reader's imagination.

Mixed Feelings About Art

The artist Ruth Lacon says that Tolkien's actions (drawing his own pictures) didn't quite match what he wrote about illustrations. She thinks pictures are very helpful for complex stories like The Silmarillion.

Pieter Collier, who put together a book of Cor Blok's art, said that Tolkien was as picky about good illustrations as he was about choosing the perfect words for his books.

| Style | How useful | Example artists |

|---|---|---|

| Wrong Doesn't match the story or feeling |

Not useful | Horus Engels Milein Cosman |

| Pretty Nice to look at, but not heroic |

For smaller stories, landscapes, maps | Pauline Baynes Tolkien's own artwork |

| Illustrative Shows something "noble or amazing" |

In or next to the story | Margrethe II of Denmark Mary Fairburn |

Artists Who Worked with Tolkien: 1937–1973

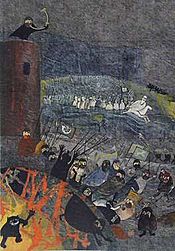

Tove Jansson, 1962

Tove Jansson, a Finnish author and artist known for her Moomin books, drew pictures for Swedish and Finnish versions of The Hobbit. In the 1962 Swedish book, she drew a very large Gollum. Tolkien was surprised to see such a giant monster next to Bilbo. He then changed the second edition of his book to say that Gollum was "a small, slimy creature."

Some experts say Jansson's art helped show how Middle-earth fantasy could look. Her illustrated book wasn't reprinted for many years, even though people liked her "expressive" pictures. This might be because a new, more realistic style became popular for fantasy art in the 1960s.

Mary Fairburn, 1968

In May 1968, English artist Mary Fairburn sent Tolkien some drawings for The Lord of the Rings. He wrote back saying they were "splendid." He added that they were "better pictures" and showed "far more attention to the text" than any others he had seen. He even started to think that an illustrated Lord of the Rings might be a good idea.

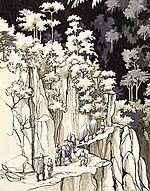

But the project didn't happen. Tolkien was 76, had hurt his leg, and was moving house. His papers got very messy. In October 1968, he told Fairburn that his publisher would take "some months" to decide. He also said black-and-white pictures were more likely. Fairburn made black-and-white versions of 26 paintings, but many were lost when she moved house. Only nine survive. Her art wasn't known to experts until 2012, and her work was finally published in the Tolkien Calendar 2015.

| A close-up of The Pass on Mount Caradhras, drawn by Mary Fairburn in 1968. Tolkien called her work "splendid" and considered an illustrated Lord of the Rings because of it. |

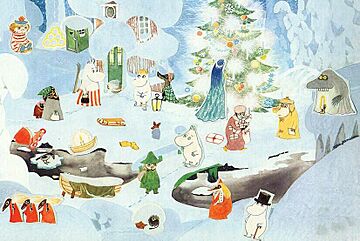

Pauline Baynes

Pauline Baynes drew pictures for some of Tolkien's shorter stories, like Farmer Giles of Ham (1949) and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (1962). In 1969, Tolkien's publisher asked her to paint "A Map of Middle-earth". Tolkien gave her his own draft maps to help. Her map was published as a poster in 1970 and became a famous image of Middle-earth.

An expert named Paul Tankard says that Tolkien "clearly admired Pauline Baynes' work" for certain things. He liked her art for his shorter stories, for landscapes, and for maps. But he didn't think her style was right for the main Lord of the Rings story. He felt her art was decorative but didn't have the "noble or awe-inspiring" quality needed for Middle-earth. He even called her dragon in Farmer Giles of Ham "ridiculous."

| Tolkien liked Pauline Baynes's decorative drawings for his shorter stories like Farmer Giles of Ham. But he thought her style wasn't "noble or awe-inspiring" enough for his main fantasy books. He found her dragon (shown here) "ridiculous." |

Margrethe II of Denmark

Princess Margrethe (who later became Margrethe II of Denmark) is a talented painter. In the early 1970s, she was inspired to draw pictures for The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien liked her woodcut-style drawings. He thought they looked similar to his own art style. In 1977, her drawings were published in the Danish translation of the book, redrawn by British artist Eric Fraser.

| A woodcut-style drawing of Éowyn fighting the Nazgul's fell beast at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, by Margrethe II of Denmark. Tolkien liked her art because it looked like his own style. |

Ted Nasmith

While still in high school, Ted Nasmith painted some pictures for The Hobbit. In 1972, he sent photos of his art to Tolkien. This included a painting of The Unexpected Party from the start of The Hobbit. Tolkien wrote back a few weeks later. He praised the work but said that Bilbo Baggins looked a bit too much like a child. This feedback encouraged Nasmith to try and draw Tolkien's stories more exactly. He later drew pictures for some editions of The Silmarillion.

Independent Artists

A Japanese View, 1965

The Japanese artist Ryûichi Terashima drew pictures for Teiji Seta's 1965 translation of The Hobbit. An expert named Robert Ellwood admired his work. He said the characters were treated "with the seriousness" they deserved. He felt that in these drawings, the characters "emerge as real, discrete personalities."

| Ryûichi Terashima's drawing of Gandalf and Bilbo at Bag End. His pictures of these characters were praised for making them seem like "real, discrete personalities." |

Maurice Sendak's Unfinished Work, 1967

The famous children's book author Maurice Sendak was asked to illustrate a special edition of The Hobbit in 1967. Only one of his sample drawings still exists, showing Gandalf with Bilbo smoking outside Bag End.

According to artist Tony DiTerlizzi, Sendak sent two drawings to Tolkien. The other one showed Mirkwood's wood-elves dancing. DiTerlizzi says Sendak's work was very clever. He used thick lines for a tired Gandalf and light, open lines for a happy Bilbo. DiTerlizzi also says that an editor accidentally called Sendak's wood-elves "hobbits." This made Tolkien angry, and he rejected the drawings, which then made Sendak angry. A meeting was planned, but Sendak had a heart attack, and the project was canceled. Another idea is that Tolkien didn't want The Hobbit to be seen as just a children's story.

| A drawing by Maurice Sendak of Gandalf and Bilbo at Bag End, 1967. The different ways he drew the two characters have been called clever and masterful. |

Through Slavic Eyes, 1976 Onwards

Russian drawings for The Hobbit from the Soviet era were often "stylized," meaning they had a special look. They were "angular, friendlier, almost cartoonish." Mikhail Belomlinsky's pictures for a 1976 translation show the three Trolls with full beards, dark clothes, and bare feet. They are holding mugs and arguing about how to cook Bilbo. Bilbo is shown with hairy legs, not just hairy feet, because the Russian word for "leg" or "foot" is the same. Belomlinsky said his Bilbo character was based on a good-natured, plump actor named Yevgeny Leonov.

| Mikhail Belomlinsky's somewhat cartoonish Russian drawing of the three Trolls arguing about how to cook Bilbo, from 1976. |

In 1981, Russian artist Alexander Korotich made a series of scraperboard engravings for The Lord of the Rings. Many of these were lost, but the ones that survived were shown in an exhibit in 2013.

- Scraperboard illustrations by Alexander Korotich

-

Frodo and Sam guided by Gollum through the Dead Marshes

-

Gwaihir the Eagle rescues Gandalf from Orthanc

In 1979, Czech artist and animator Jiří Šalamoun, known for his cartoon dog TV show, illustrated a Czech translation of The Hobbit. Šalamoun changed his usual children's style to fit the book. But some say the result was "rather far... from Tolkien's original" vision.

| A close-up of Jiří Šalamoun's unique drawing of An Unexpected Party for the 1979 Czech Hobbit book. |

Russian artist Sergey Yuhimov drew pictures for a 1993 edition of The Lord of the Rings in the style of icons from the Russian Orthodox Church. This use of religious symbols might have added more layers of meaning to Tolkien's story. His work has been called "vivid, stylistically Medieval, religious-icon-saturated."

| Sergei Yuhimov drew pictures for a 1993 Russian Lord of the Rings in the style of icons from the Russian Orthodox Church. |

Covers and Calendars, 1978 Onwards

Paul R. Gregory's Middle-earth paintings, started in 1978, have appeared on many rock music albums. However, some artists say his work doesn't always match Tolkien's text.

The Brothers Hildebrandt, Tim and Greg, were famous for their Tolkien Calendars, which came out between 1976 and 2006. Illustrator John Howe said these calendars inspired him. They showed him that Tolkien's novels could indeed be illustrated.

Calligraphy and Illumination, 1990

Tom Loback helped people appreciate Tolkien's world through his art and his studies. An expert named Bradford Lee Eden said Loback's work was "unique." He used both Tolkien's special writing styles (Cirth and Tengwar) and Elvish languages (Quenya and Sindarin) in his art. He also copied the style of medieval illuminated manuscripts (fancy handwritten books). In 1990, Mythlore magazine asked Loback and three other artists to draw a scene from The Silmarillion.

- Medieval-style ''Silmarillion'' images with Elvish calligraphy by Tom Loback

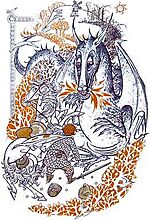

Fantasy and Botany, 2017

Tolkien once said he loved illustrated botany books and the "unfamiliar flora[s]" of new places. He mentioned a fictional flower called Niphredil, saying it was like a delicate snowdrop but "lit by a light" from another world.

Artist Graham A. Judd made woodcut drawings for his father, botanist Walter S. Judd's 2017 book, Flora of Middle-earth. These woodcuts show both the real features of plants and symbolic scenes from Tolkien's stories. This mixes "art and science" together.

| A close-up of a woodcut drawing of the fictional Niphredil flower, which looks like a snowdrop. It shows Aragorn and Arwen on a lawn of these flowers. From the 2017 Flora of Middle-earth, by Graham A. Judd. It combines fantasy and botany. |

Classical Realism, 2019

American artist Donato Giancola calls himself a "classical-abstract-realist" who works with science fiction and fantasy. He has painted many pictures of J. R. R. Tolkien's world. One writer called him "the Caravaggio of Middle-earth" and a "Tolkien neoclassicist." They suggested that Giancola's "The Tower of Cirith Ungol," showing an Orc hurting Frodo, could almost be by an old artist known for drawing supernatural scenes.

How Peter Jackson's Films Changed Art: 2001 Onwards

Concept Art

Tolkien artists John Howe and Alan Lee became very well-known by the late 1900s for their Middle-earth art. Lee drew for illustrated versions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Howe created cover art for many Tolkien books.

Both artists worked as "concept artists" for Peter Jackson's 2001–2003 Lord of the Rings film trilogy. Their designs directly led to how things looked in the movies. In 2004, Lee won an Academy Award for Best Art Direction for The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Ted Nasmith was asked to work on the films too, but he said no.

From Fan Art to Recognized Artistry

The movies reached a huge audience. This made the artistic ideas from Jackson's artists very influential. It created a common image of Middle-earth and its people, like Elves, Dwarves, Orcs, and Hobbits, shared by Tolkien fans and artists.

However, some fan artists get ideas from other places. Anna Kulisz said her painting of Arwen sewing Aragorn's banner was inspired by a 1911 painting called Stitching the Standard.

-

Stitching the Standard, by Edmund Leighton, 1911

German artist Anke Eißmann was already known for her Tolkien art, which started as fan art. She made many paintings of scenes from The Silmarillion. One expert, Mike Foster, said her work was influenced by Peter Jackson's films.

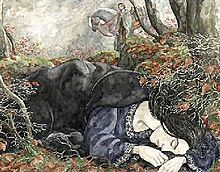

| Anke Eißmann's painting The Parting (of Beren from Lúthien), from The Silmarillion. Her art has been influenced by Peter Jackson's films. |

Jenny Dolfen has created many watercolor paintings of scenes from The Silmarillion. She is known as one of the best self-taught Middle-earth artists. She has become famous among Tolkien fans, making her both a fan artist and a recognized, published artist.

Dolfen has won three awards from The Tolkien Society for her paintings:

- In 2014, for "Eärendil the Mariner," a painting of Eärendil.

- In 2018, for "The Hunt," showing Finrod Felagund hunting with Maedhros and Maglor.

- In 2020, for a T-shirt design called "The Professor," celebrating 50 years of The Tolkien Society. It showed Middle-earth characters and places inside the outline of a pipe-smoking J. R. R. Tolkien.

See also

- Inger Edelfeldt, who drew many cover illustrations for Swedish editions of Tolkien's books