Isaac Babel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

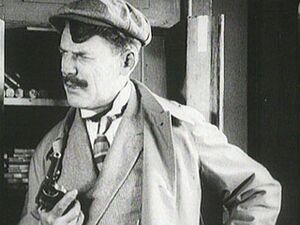

Isaac Babel

Исаак Бабель |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 13 July [O.S. 1 July] 1894 Odessa, Kherson Governorate, Russian Empire (now Odesa, Ukraine) |

| Died | 27 January 1940 (aged 45) Butyrka prison, Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | journalist, short story writer and playwright |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire Soviet Union |

| Notable works | Red Cavalry Odessa Stories |

| Signature | |

|

|

Isaac Babel (born July 13, 1894 – died January 27, 1940) was an important Soviet writer, journalist, and playwright. He is famous for his books Red Cavalry and Odessa Stories. Many people called him "the greatest prose writer of Russian Jewry." Sadly, Babel was arrested by the NKVD (the Soviet secret police) in 1939 on false charges. He was executed in 1940.

Contents

Isaac Babel's Early Life and Education

Isaac Babel was born in Odessa, a city in the Russian Empire (now Ukraine). His parents, Manus and Feyga Babel, were Jewish. When he was young, his family moved to another city, Nikolaev, but later returned to Odessa. Babel often used the Moldavanka area of Odessa as a setting for his stories, like Odessa Stories.

Even though Babel's stories sometimes made his family seem poor, they were actually quite well-off. His father was a successful dealer in farm tools.

Babel wanted to go to a good school in Odessa. However, there was a rule called the Jewish quota, which limited how many Jewish students could attend. Even though Babel had good grades, his spot was given to another boy whose parents had bribed school officials. Because of this, he was taught at home by private teachers.

Besides regular school subjects, Babel also studied the Talmud (Jewish religious texts) and music. He knew Yiddish and Hebrew well. He also loved the works of French writers like Maupassant and Flaubert. Babel even wrote his first stories in French. He was good at understanding people from all walks of life, like farmers, soldiers, and artists.

Babel tried to go to Odessa University, but again, he was stopped because he was Jewish. So, he went to the Kiev Institute of Finance and Business instead. There, he met Yevgenia Borisovna Gronfein, who later became his wife.

Babel's Writing Career

Starting as a Writer

In 1915, Babel finished his studies and moved to Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg). This was against the rules that limited where Jewish people could live. He was very good at French, Russian, Ukrainian, and Yiddish.

In Petrograd, Babel met Maxim Gorky, a famous Russian writer. Gorky published some of Babel's early stories in his magazine. Gorky told Babel to get more life experience, and Babel always said he owed a lot to Gorky. One of Babel's well-known stories, "The Story of My Dovecote," was dedicated to Gorky.

During the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War, Babel worked in different jobs. He was a translator for the secret police (Cheka) and a reporter for a newspaper. He said that his work as a journalist helped him gather many facts and meet interesting people. This helped him greatly when he started writing fiction.

Family Life and Influences

Babel married Yevgenia Gronfein in 1919. Their daughter, Nathalie Babel Brown, later became an expert on her father's work. In the mid-1920s, Yevgenia moved to France because she did not like communism. Babel visited her in Paris several times. He also had a long relationship with Tamara Kashirina, with whom he had a son, Emmanuil. Later, Babel lived with Antonina Pirozhkova, and they had a daughter named Lydia.

Antonina Pirozhkova remembered Babel telling her about important books to read. He made a list that included ancient Greek and Roman writers, as well as European classics like Cervantes and Flaubert.

Red Cavalry

In 1920, Babel joined the 1st Cavalry Army during the Polish-Soviet War. He kept a diary of the terrible things he saw during the war. This diary later became the basis for his famous collection of short stories called Red Cavalry. These stories, like "Crossing the River Zbrucz," showed the harsh realities of war, which was very different from the usual revolutionary stories.

Babel's honest writing made some powerful people angry. Marshal Semyon Budyonny, a military leader, was very upset by Babel's descriptions of his soldiers and wanted Babel punished. However, Maxim Gorky helped protect Babel and made sure his book was published. Red Cavalry was translated into English in 1929 and many other languages later.

The famous Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges said that the writing style of Red Cavalry was beautiful, even though the scenes were brutal.

Odessa Stories

Back in Odessa, Babel began writing Odessa Stories. These stories are set in the Jewish neighborhood of Moldavanka. They were published between 1921 and 1924 and collected into a book in 1931. The stories are about Jewish gangsters in Odessa, especially a fictional mob boss named Benya Krik. Benya Krik is a well-known character in Russian literature. These stories inspired a 1927 movie and a play called Sunset.

The play Sunset was performed in several cities, including Moscow. Some critics liked it, but others felt it was not clear enough about its message. However, famous people like Boris Pasternak and Sergei Eisenstein admired the play. Eisenstein, a filmmaker, thought it showed how money and power affected a family, much like the writings of Émile Zola.

Maria

Babel's play Maria showed problems in Soviet society, like corruption and illegal trading. It also showed innocent people being treated unfairly. Maxim Gorky warned Babel that the play might cause him trouble because it did not follow the official style of "socialist realism."

Babel himself was critical of his own work, but the play was popular in Western countries. However, the Soviet secret police (NKVD) stopped its performance in Russia in 1935. Maria was not performed in Russia until after the Soviet Union ended.

Carl Weber, a theater director, said that Maria was controversial because it showed both sides of the Russian Civil War (Bolsheviks and old society members) without taking a side. It suggested that what happened after the revolution might not have been the best for Russia.

Life in the 1930s and Growing Silence

In 1930, Babel traveled in Ukraine and saw the harsh effects of forced collectivization, where the government took control of farms. He privately told Antonina Pirozhkova that the good times were gone because of the famine in Ukraine and the destruction of villages.

As Joseph Stalin gained more control, writers were forced to follow "socialist realism," a style that glorified Soviet life. Babel became quieter and wrote less. He was criticized for not producing enough work. At a writers' meeting in 1934, Babel jokingly said he was becoming "the master of a new literary genre, the genre of silence."

Despite this, Babel had a comfortable life compared to many others. He had a villa outside Moscow and was allowed to visit his wife and daughter in Paris. However, he struggled with the idea of returning to the Soviet Union, wanting to be "a free man" but also needing to make a living. He eventually returned to the Soviet Union in 1933.

He also worked on screenplays for films, including Bezhin Meadow, which was about a child who informed the Soviet secret police.

Arrest and Execution

On May 15, 1939, four NKVD agents arrested Isaac Babel at his home near Moscow. His common-law wife, Antonina Pirozhkova, was with him. Babel was taken to Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. He was calm during his arrest, but worried about his mother and daughter.

Nadezhda Mandelstam, another writer, said that the NKVD agents often made up stories about how dangerous their arrests were. She heard a story that Babel had resisted arrest and wounded an officer. But she said this was likely false, as Babel was a careful man who probably never held a pistol.

After his arrest, Isaac Babel became a "nonperson" in the Soviet Union. His name was removed from books and school lessons. He could not be mentioned in public. For example, when a film he worked on was released, his name was removed from the credits.

Babel was held in Lubyanka and Butyrka Prisons for eight months. He was accused of being a Trotskyite, a terrorist, and a spy for Austria and France. At first, he denied everything. But after three days, he "confessed" and named other people, including his friends Sergei Eisenstein and Ilya Ehrenburg. It is believed he was tortured and beaten to make these false confessions.

In October 1939, Babel took back his confessions, saying he had slandered people. This caused delays for the NKVD.

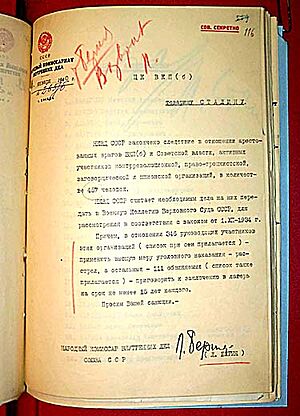

On January 16, 1940, Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD, sent a list of 457 people to Stalin, recommending that 346 of them, including Isaac Babel, be executed. Stalin approved the list.

Babel's trial took place on January 26, 1940, and lasted only about twenty minutes. He was executed at 1:30 AM on January 27, 1940. His last words recorded were: "I am innocent. I have never been a spy. I never allowed any action against the Soviet Union. I accused myself falsely. I was forced to make false accusations against myself and others... I am asking for only one thing—let me finish my work."

Babel's ashes were buried in a common grave at the Donskoy Cemetery. After the Soviet Union ended, a plaque was placed there for the victims of political repression. For many years, the official Soviet story was that Babel died in a labor camp in 1941. His execution is seen as a great tragedy in literature.

Rehabilitation and Lost Writings

On December 23, 1954, during a period called the Khrushchev Thaw, Babel was officially cleared of all charges. The case against him was closed because there was no evidence of a crime.

After this, Babel's books were published again and praised. His friend Konstantin Paustovsky helped bring his work back into public view. New collections of his works were published in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1980s. However, some parts of his writings, like mentions of Trotsky, were still censored until the late 1980s.

Antonina Pirozhkova spent nearly 50 years trying to get Babel's lost writings back. These included his translations of Sholem Aleichem's works from Yiddish into Russian, and several unpublished stories and novellas. Babel had been working on a novella called "Kolya Topuz" about a former Odessa gangster adapting to Soviet life.

However, in 1987, KGB agents told Pirozhkova that Babel's manuscripts had been burned.

Isaac Babel's Legacy

Many famous writers have praised Isaac Babel. Maxim Gorky called him "the best Russia has to offer." Konstantin Paustovsky said Babel was "the first really Soviet writer" for them.

Judith Stora-Sandor, one of Babel's biographers, said that Babel's writing style was French, his view of the world was Jewish, and his sad fate was very Russian.

Babel's first wife, Yevgenia, did not know about his other family or his execution for many years. She believed he was still alive in exile. In 1956, Ilya Ehrenburg told her the truth.

Babel's daughter, Nathalie Babel Brown, became a leading expert on his life and work. She edited his complete works, which were published in 2002. She passed away in 2005. His other daughter, Lydia Babel, also moved to the United States.

Babel's play Maria was popular in Western colleges in the 1960s but was not performed in Russia until 1994. Its first American performance was in 2004.

Many American writers have been influenced by Babel. James Salter called him his favorite short-story writer, praising his style, structure, and authority. George Saunders said that reading Babel helps him understand the difference between an okay sentence and a truly masterful one.

Memorials

A memorial to Isaac Babel was put up in Odesa, Ukraine, in September 2011. There was also a special reading of his stories with music. The city also has a street named Babelya Street in the Moldavanka area.

See also

In Spanish: Isaak Bábel para niños

In Spanish: Isaak Bábel para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |