Jacobite Army (1745) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jacobite Army |

|

|---|---|

Jacobite standard, 1745

|

|

| Active | 1745–1746 |

| Allegiance | House of Stuart |

| Size | 9,000 to 14,000 |

| Engagements | Jacobite rising of 1745 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Charles Edward Stuart Lord George Murray John Drummond James Drummond, 3rd Duke of Perth John William O'Sullivan Viscount Strathallan † |

The Jacobite Army was a military force formed by Charles Edward Stuart, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and his supporters. They were called Jacobites because they wanted to bring back the House of Stuart royal family to the British throne. This army was active during the 1745 Rising, a major rebellion in Scotland.

The army started small, with fewer than 1,000 men in August 1745. They quickly grew and won an important battle at Prestonpans in September. About 5,500 Jacobite soldiers then marched into England in November, reaching as far south as Derby. They later retreated safely back to Scotland.

At its largest, the Jacobite Army had between 9,000 and 14,000 soldiers. They won another battle at Falkirk in January 1746. However, they faced a final defeat at the Battle of Culloden in April. Even though many Jacobites still wanted to fight, they didn't have enough support or supplies. The government forces were also much larger, which led to the end of the rebellion.

Many people used to think the Jacobite Army was mostly made up of Gaelic-speaking Highlanders using old weapons. But historians now know it was more diverse. It included many Scots from the Lowlands and north-east, as well as soldiers from France, Ireland, and England. These soldiers were trained and organized using modern European military methods of the time.

Contents

How the Jacobite Army Was Formed and Led

Charles Edward Stuart left France in July 1745, hoping to start his rebellion. He planned to bring weapons and 70 volunteers from the Irish Brigade (a French army unit). However, his ship carrying these supplies was stopped by a British warship and had to turn back. This meant Charles arrived in Scotland with very few weapons and only a small group of companions, known as the "Seven Men of Moidart."

When Charles first arrived, many Scottish leaders told him to go back to France. But Lochiel decided to join him, which convinced enough others to start the rebellion. On August 19, the Jacobite Army officially began at Glenfinnan. At first, it had about 1,000 men, mostly from the Clan Cameron and other Highland clans.

Charles was the leader, but he didn't have much military experience. So, John O'Sullivan, an Irish officer from the French army, became his main advisor. O'Sullivan was in charge of organizing the army, training the soldiers, and managing supplies. He set up the army like European forces, using a new "divisional" structure. This helped the Jacobites move very quickly.

As the army marched towards Edinburgh, more people joined. By the time of the Battle of Prestonpans in September, their numbers had grown to about 2,500.

One important person who joined was Lord George Murray. He had been part of earlier Jacobite rebellions in 1715 and 1719. Some people, including Charles's Scottish advisor, didn't trust Murray because he had previously accepted a pardon from the British government. However, Murray was a very skilled military leader.

Murray and O'Sullivan often disagreed. Murray believed that Highland customs were better for their soldiers, while O'Sullivan wanted to use European military drills. Both had some good points. Many Scots had served in European armies, but traditional clan warfare was different. Most Highland soldiers were farmers who weren't used to long periods of fighting.

Training was a big challenge because the Jacobites didn't have enough weapons or ammunition for practice. After big battles like Prestonpans and Falkirk, many clan soldiers would go home to protect their families and belongings. This made it hard to keep the army together for continuous fighting.

Charles saw his generals as people who should simply follow his orders. But Murray disagreed, believing they should have a say in strategy. Charles eventually set up a "Council of War" to make military decisions. This council had 15-20 senior leaders, mostly Highlanders, who provided most of the soldiers. This meant that decisions often reflected their priorities.

When the Jacobite army of about 5,500 men invaded England in November, command was shared among three generals: Murray, Tullibardine, and James Drummond. In practice, Murray led most of the time because Tullibardine was ill and Drummond was less experienced.

Charles's relationship with his Scottish leaders became difficult, especially after the army retreated from Derby. He often accused the Scots of being traitors. Murray suggested they stop trying to invade England and instead focus on a rebellion in the Highlands.

In late November, John Drummond, Perth's brother, arrived from France with money, weapons, and trained soldiers. He took over command in Scotland. His arrival caused more disagreements among the leaders. At the battles of Falkirk and Culloden, O'Sullivan was in charge, with Murray, Perth, and Drummond leading different groups of soldiers.

Who Joined the Jacobite Army?

Unlike earlier rebellions, many people joined the Jacobites in 1745 for reasons other than just loyalty to the Stuart family. About 46% of the Jacobite army came from the Highlands and Islands.

One big reason for joining in the Highlands was the traditional clan system. This system meant that tenants (people living on a landlord's land) had to provide military service to their chief. Most Highland soldiers came from a few western clans whose leaders, like Lochiel and Keppoch, joined the rebellion. However, this system was usually for short battles, not long wars. It was hard to keep the army together for a long time.

The Jacobites also recruited outside the Highlands, though sometimes people were forced to join. About 20% of the soldiers came from Perthshire, where leaders like Lord George Murray had strong connections. Another 24% came from the north-east of Scotland, especially from towns like Montrose, Stonehive, and Peterhead. These areas had been loyal to the Stuarts for a long time.

However, not everyone supported the Jacobites. Big cities like Edinburgh and Glasgow remained loyal to the government. Even within "Jacobite" clans, some important leaders refused to join.

Why Did People Join?

People joined the Jacobite Army for different reasons. Some volunteered for adventure, while others were truly loyal to the Stuart family. Charles tried to get support from groups who felt left out, whether for religious or political reasons.

A very common reason for Scots to join was their opposition to the 1707 Union that joined Scotland and England. After 1708, the exiled Stuarts promised to undo this Union. Charles even published statements promising to end the Union and reject the current king. He also suggested ending the unpopular Malt Tax, which made many people see the rebels as "deliverers of their country."

The Stuarts also supported religious freedom because they were Catholic. But this didn't have a huge impact. Most Scots were Protestant, whether Episcopalian or Presbyterian. By 1745, many Episcopalians who didn't swear loyalty to the current king lived along the north-east coast, and many soldiers came from these areas.

In England, there was less support. Many English Tories had stopped supporting the Stuarts because they worried about the Catholic Church gaining too much power. The only English town that provided many soldiers was Manchester, which also had a group of people who didn't swear loyalty to the king. Most Jacobite soldiers were Protestant, even though some officers were Catholic.

Regiments were formed by captains who recruited their own companies. This meant they needed people with money and social standing to attract, equip, and pay soldiers. This was easier in the Highlands due to clan obligations. In some areas, many officers were volunteers, while the regular soldiers were essentially forced to join.

Clan Obligations and Being Forced to Join

Many units were formed because of a feudal system where tenants had to provide military service for their land. While this sounds like an old-fashioned army, it was more complicated. In the north-west Highlands, clan chiefs could demand a certain number of armed men from their tenants. This worked well because tenants felt a strong connection to their chief.

In other areas, like Perthshire, tenants held their land in exchange for military service, regardless of their clan. Rents were kept low because of this expectation, and many tenants didn't have written leases, which put more pressure on them to join.

Historians agree that forcing people to join, or "impressment," was a big factor. This was especially true for Highlanders, who were used to short periods of fighting. After battles, many would go home to secure their loot, which caused problems for the army.

Some chiefs, like Lochiel and Keppoch, were accused of threatening violence or eviction to make their tenants join. Lochiel's brother, Archibald Cameron, was even betrayed and executed later, supposedly because of his role in forcing recruits in 1745.

Landowners in the north-east also had trouble recruiting. One Jacobite officer wrote that Lord Lewis Gordon was "putting into prison all who are not willing to rise." Some recruits were so unwilling that they didn't even know the name of the unit they had joined. Sometimes, people made decisions against their chief's wishes. For example, some of Keppoch's men deserted early on after a "private quarrel" with him. Poor harvests in the Highlands in 1744 and 1745 also influenced some farmers to enlist.

Deserters and Conscripts

The Jacobite Army tried to recruit prisoners taken in battle. These "deserters" became an important source of new soldiers. Many were taken from British army regiments after their garrisons surrendered. Some of these men had actually deserted from the British army in Europe before returning to Scotland.

The Jacobite army itself had problems with desertion. Later in the rebellion, they used a system where landowners had to provide one equipped man for every £100 of rent. These quotas were filled in different ways. Sometimes, people paid someone else to serve in their place. These hired men were usually treated kindly after the rebellion.

Jacobite recruiters couldn't be picky. They took many people who wouldn't have met later army standards. While some descriptions show Highlanders as tall, healthy men, records of prisoners after the rebellion show otherwise. The average height was about 5 feet 4 inches. Many were over 50 years old, and some were as young as 16 or 17. Observers noted the "great number of boys and old men" in the army. Some even had disabilities, like being deaf, blind in one eye, or having club feet.

French Regular Soldiers

When Charles sailed from France, he was supposed to bring many weapons and soldiers from the French Army's Irish Brigade. But his ship was stopped by a British warship, and both ships had to return to port. This was a big setback, as Charles lost the trained soldiers who were meant to be the core of his army.

Jacobite agents kept trying to get foreign support. The French government eventually agreed to help in October 1745. Regular troops in the Jacobite army came from three main groups:

- The Royal Scots (or Royal Ecossais): About 400 men, recruited in France, who landed in Scotland in November 1745.

- The Irish Brigade: Each of their six regiments sent 50 men, but only half made it past the British navy.

- The Fitzjames cavalry regiment: Only one of their four squadrons reached Scotland, and they didn't have their horses.

In total, there were probably only about 600 to 700 regular, trained soldiers. These soldiers were important because they were treated as prisoners of war if captured, not rebels. At Culloden, the Irish detachment suffered heavy losses, but their sacrifice helped Charles escape. However, there were never enough of them to make a huge difference.

How the Army Was Organized

Infantry (Foot Soldiers)

The Jacobite foot soldiers were first split into two main groups: 'Highland' and 'Low Country Foot'. These were led by Murray and Perth. Like the British army, they were divided into regiments, usually with one battalion (a large group of soldiers). Some had two battalions, like French armies. Each battalion was supposed to have 200 to 300 men, but often had fewer. These were then split into smaller companies. Some regiments even had special grenadier companies.

Highland regiments were traditionally organized by clan, with officers from their own clan leaders. This sometimes made units too small, so they tried to combine them. Officers were often chosen based on how many recruits they brought in. O'Sullivan noted that Highlanders preferred to stay with their own clan and often had too many officers for the number of soldiers.

While Lowland recruits adapted well, Highland traditions didn't always fit the European-style army O'Sullivan wanted. Even professional soldiers needed constant training with their firearms. The Jacobites lacked time, weapons, and ammunition. However, Murray did teach them a simpler, effective drill. Some Lowland regiments might have been taught musket drills similar to the British army. Most Jacobite professional soldiers were trained in France, so their tactics showed French influence, focusing on quick attacks rather than continuous firing. This suited the Jacobite troops' training levels.

| Unit | Colonel | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cameron of Lochiel's Regiment | Donald Cameron of Lochiel | This regiment was made up of Lochiel's own tenants. It was a big part of Charles's early support, with about 700 men at its strongest. They fought at Culloden and suffered heavy losses. |

| Atholl Brigade | Lord Nairne; Robert Mercer of Aldie †; Archibald Menzies of Shian † | This group of 500 men from Perthshire was led by Lord George Murray. Many soldiers deserted, and they had heavy casualties at Culloden. |

| Appin Regiment | Charles Stewart of Ardsheal | Made up of Stewart tenants from Appin, this regiment joined Charles in August. They fought in all major battles, including Prestonpans, Falkirk, and Culloden. |

| MacDonald of Keppoch's Regiment | Alexander MacDonald of Keppoch † | Keppoch brought about 300 men from Lochaber. They were known for poor discipline but fought well at Prestonpans and Falkirk. They suffered many losses at Culloden. |

| MacKinnon's Regiment | John Dubh MacKinnon of MacKinnon | Raised in Skye, this regiment served with Keppoch's for most of the rebellion. |

| MacDonald of Clanranald's Regiment | Ranald MacDonald, younger, of Clanranald | This regiment was from Moidart and was one of the first to join Charles. They fought at Prestonpans, Falkirk, and Culloden. |

| MacDonnell of Glengarry's Regiment | Donald MacDonnell of Lochgarry | One of the largest Highland regiments, Glengarry's fought throughout the Rising, including at Clifton. They had up to 500 men at Culloden. |

| Lady Mackintosh's Regiment | Alexander MacGillivray of Dunmaglass † | This unit was raised in the Inverness area, partly by forcing men to join. They had very heavy losses at Culloden. |

| Lord Lovat's Regiment | Charles Fraser of Inverallochie † | Raised from the tenants of Lord Lovat, one battalion of 500 men fought at Culloden. |

| Maclachlans' Regiment | Lachlan Maclachlan; † Charles Maclean of Drimnin † | This battalion was raised in Argyll and later formed a separate regiment. They suffered heavy losses at Culloden. |

| Chisholm's Battalion | Roderick Og Chisholm † | A small unit of about 80 men that joined Charles shortly before Culloden, where many were killed. |

| Manchester Regiment | Francis Towneley | Raised in Manchester, England, this regiment had about 200 volunteers. Most were left to guard Carlisle and surrendered there. |

| Royal Ecossais | John Drummond | This regiment was raised in France from Scottish exiles and landed in Scotland in December 1745. It had about 350 men at Culloden. |

| Irish Picquets | Walter Valentine Stapleton † | These were Irish regular soldiers from the French army who arrived in December 1745. They fought bravely at Culloden. |

| Regiment Berwick | Another Franco-Irish unit. One group landed in February 1746 and fought at Culloden. | |

| Lord Lewis Gordon's Regiment | Lord Lewis Gordon | This regiment was raised in Aberdeenshire and Banffshire. Some men volunteered, while others were forced to join. They fought at Culloden. |

| Lord Ogilvy's Regiment | David, Lord Ogilvy | A large unit raised in Forfarshire. It fought at Culloden and then regrouped before disbanding. Lord Ogilvy later escaped to Sweden. |

| John Roy Stewart's Regiment | John Roy Stewart | This unit, also called the 'Edinburgh Regiment', was raised in Edinburgh. It included city workers and British army "deserters." They fought in the front line at Culloden. |

| Glenbucket's Regiment | John Gordon of Glenbucket | Raised early in the rebellion, partly by forcing men to join. They were equipped with weapons taken from the Battle of Prestonpans and fought at Culloden. |

| Duke of Perth's Regiment | James Drummond, 3rd Duke of Perth | This large regiment included Highlanders, Lowlanders, and English companies. It was 750 strong during the invasion of England. |

| MacPherson of Cluny's Regiment | Ewen MacPherson of Cluny | Cluny and his company joined the Jacobite army after Prestonpans. This regiment was still on its way to join the main army when Culloden was fought. |

| Earl of Cromartie's Regiment | George Mackenzie, Earl of Cromartie | Raised in the northern Highlands, partly by impressment. It was destroyed in an ambush before Culloden. |

| Kilmarnock's Foot Guards | William Boyd, Earl of Kilmarnock | Originally cavalry, this unit was changed into a foot regiment in early 1746. It was expanded with impressed men. |

| Crichton of Auchingoul's Regiment | James Crichton of Auchingoul | A small unit raised in Aberdeen, later merged into Kilmarnock's Foot Guards. |

| Bannerman of Elsick's Regiment | Sir James Bannerman | Another Aberdeenshire regiment, likely merged into Kilmarnock's regiment later in the campaign. |

Cavalry (Horse Soldiers)

The Jacobite cavalry (soldiers on horseback) were small in number. They mostly did scouting and other light cavalry tasks. Even so, they often performed better than the regular cavalry opposing them. Most of these units had two troops (smaller groups of cavalry) and had many officers, as commissions were given to reward Jacobite supporters.

| Unit | Colonel | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lifeguards | David Wemyss, Lord Elcho; Arthur Elphinstone, 6th Lord Balmerino | Charles had a mounted lifeguard from the start. It grew to be one of the larger cavalry units, with many young men from Dundee and Edinburgh. They had a special uniform: blue coats with red facings. |

| Scotch Hussars | John Murray of Broughton | A single troop of 50 men raised in Edinburgh. They were called "hussars," a type of light cavalry new to Britain. They were trained to operate like continental light cavalry. |

| Strathallan's Horse | William Drummond, 4th Viscount Strathallan † | Also known as the Perthshire Horse, this regiment was raised early in the rebellion. Many volunteers were small landowners. They fought throughout the Rising. |

| Lord Kilmarnock's Horse | Lord Kilmarnock | This small unit was raised in West Lothian and Fife. In March 1746, their horses were given to the newly arrived French cavalry, and the men became foot soldiers. |

| Pitsligo's Horse | Alexander Forbes, 4th Lord Forbes of Pitsligo | Pitsligo, the Jacobite 'General of Horse', raised this cavalry regiment in Aberdeenshire. Its remaining horses were also given to the French cavalry in March. |

| Fitzjames Cavallerie | William Bagot | A unit of Irish exiles in French service. Most were captured at sea, and only one squadron landed in Scotland without horses. Half were later mounted using horses from other Jacobite cavalry units. |

Artillery (Cannons)

The Jacobite artillery (cannons and their crews) was small and didn't have many resources. But it was better organized than often thought. For most of the campaign, it was led by Captain James Grant, a French regular officer. Grant arrived in October 1745 with 12 French gunners to train new recruits. He organized two companies of soldiers to be gunners.

The army always needed more heavy weapons. During the invasion of England, they used six old cannons captured at Prestonpans. They also had six modern cannons from France and an old cannon from Blair Atholl. Some of these guns were left at Carlisle.

Larger siege cannons arrived from France in November. At the Siege of Stirling Castle, the artillery was led by a French engineer named Mirabel de Gordon. His abilities were not highly regarded by the Scots, and the cannons were not used well. Most of the siege artillery was left behind when the Jacobites retreated.

At Fort Augustus in March, the artillery had some success. A French engineer used mortars to force the fort to surrender. However, at Culloden, the Jacobite cannons were quickly overwhelmed.

Equipment and Clothing

Old pictures of the Jacobite army often show men in Highland dress with broadswords and targes (small shields). While this image was used in government messages and heroic stories, it wasn't entirely accurate. While officers and some volunteers might have carried a sword, most soldiers actually used guns (firelocks) with bayonets. They were trained in modern military practices.

At the beginning, many Highland soldiers were poorly armed. Some had old guns, farm tools like pitchforks, or a few axes and swords. Officers and cavalry often had pistols. After their victory at Prestonpans and more shipments from France and Spain, the army got modern muskets with bayonets. These became the main weapons for most soldiers. Many soldiers found the targes (shields) to be a burden and threw them away before Culloden.

Even so, Jacobite officers knew that the "Highland charge" could scare inexperienced enemy troops. The broadsword caused dramatic wounds, even if bullets were more deadly. Lord George Murray noted that at Penrith, Glengarry's regiment just had to "throw their plaids" (a signal for a charge) for local militia to run away. The Jacobite tactic was to charge, hoping the enemy would break and run. If the charge was stopped, like at Culloden, the Highlanders were left throwing stones because they couldn't respond with their swords.

The Jacobite Army didn't have a formal uniform. Most men wore their own clothes. Lowlanders wore coats and breeches, while Highlanders wore short coats and plaids. Some exceptions were Charles's Lifeguard, who wore blue coats with red trim, and the Royal Ecossais and Irish Brigade, who wore traditional red coats. The well-dressed cavalry were used to impress people in towns. An observer at Derby said the cavalry looked like "fine young men," but the infantry "appeared more like a parcel of chimney sweeps."

As a sign of loyalty to the Stuarts, all Jacobite soldiers wore a white cockade (a ribbon badge). Many also wore the distinctive blue bonnet. They often used various forms of the saltire (a diagonal cross) as a badge on their flags. As the rebellion continued, the Jacobite leaders started using tartan cloth as a simple uniform for all troops, regardless of where they came from. Tartan was easy to get and helped identify the Jacobites. It also became a symbol of Scottish identity. However, some reports suggested that Lowlanders were put in Highland dress to make the number of Highlanders seem larger.

Pay for Soldiers

Records show that soldiers were paid regularly for most of the campaign. Private soldiers received 6 pence per day, while sergeants got 9 pence. Officers' pay ranged from 1 shilling 6 pence for ensigns to 6 shillings for colonels. However, how often regiments were paid varied. Some were paid in advance, others later.

By February 1746, pay rates started to drop and payments became delayed. By March, it seems money had run out completely. Instead of money, soldiers were paid weekly with oatmeal.

Army Size and What Happened After Culloden

Detailed records suggest that the Jacobite army had a maximum of about 9,000 active soldiers. The total number of people who joined during the campaign, not counting French and Irish soldiers, might have been as high as 13,140. The difference between these numbers is likely due to soldiers deserting. Also, some recruitment figures might have been too optimistic.

Most of the Jacobite casualties (around 1,500) happened at the Battle of Culloden. After the rebellion, many Jacobites went into hiding or simply returned home. A total of 3,471 men were recorded as prisoners. About 40 "deserters" were immediately executed, and 73 were executed after a trial. Around 936 were sent to colonies or volunteered for transportation. About 700-800 were forced to join the British Army, often for service overseas. Most of the remaining prisoners were pardoned by a law in 1747.

Images for kids

-

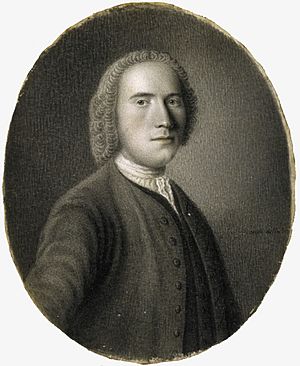

Painting suggested to be Donald Cameron of Lochiel (1695- 1748); his support was vital in the early stages.

-

The Black Watch at Fontenoy, April 1745; an example of highly effective and conventionally trained Highland troops.

-

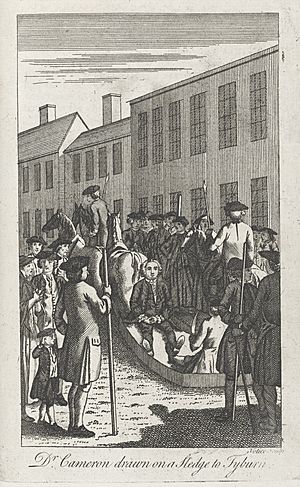

Enlisting soldiers by William Hogarth around 1750. Alcohol often played a part in recruiting for all armies.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |