James Bowen (railroad executive) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

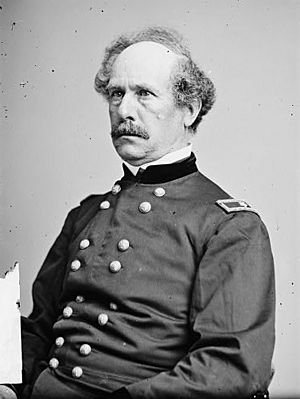

James Bowen

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 25, 1808 New York, New York |

| Died | September 29, 1886 (aged 78) Hastings-on-Hudson, New York |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Union Army |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

James Bowen (born February 25, 1808 – died September 29, 1886) was an American leader in the railroad business. He was the President of the Erie Railroad. He also served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Contents

James Bowen's Early Life and Career

James Bowen was born in New York City on February 25, 1808. His father was a rich merchant, so James received a good education. He was naturally good at business and was very interested in public affairs. He knew many important people of his time.

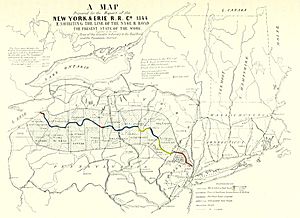

Early in his life, Mr. Bowen bought a large property in Westchester County. This became his home. He became interested in railroads when the New York and Erie Railroad was just starting. In 1839, he was chosen to be a director. He became vice-president and treasurer in 1840. By October 1841, he was the president of the company.

In 1857, the Metropolitan Police of New York City was created. Governor King appointed James Bowen as one of the first Police Commissioners. He became the president of the Board. He was in charge during a time when the city's mayor, Fernando Wood, tried to stop the new police force from taking over.

James Bowen's Role in the Civil War

During the American Civil War, James Bowen helped create six volunteer army groups. He stopped being president of the Police Board at the end of 1862. He was then made a general of a brigade, which was mostly made up of the soldiers he had recruited.

General Bowen went to New Orleans with his troops. He served there for one year. After that, he was appointed as the provost marshal for a large area. This area included Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama. He was in charge of these states as the United States government took back control.

Just before the war ended, General Bowen had to leave the army because of his health. He returned home. Soon after, he was appointed as a Commissioner of Charity and Correction for New York City. While he was in this job, the government increased the salary for commissioners. General Bowen thought this increase was wrong. He refused to take the higher salary. Because of his strong stand, the law that allowed the increase was removed.

General Bowen served two terms as a charity commissioner. He started the ambulance system for hospitals. He also greatly improved Bellevue Hospital. He made sure that the best doctors worked there. This helped Bellevue Hospital become a very respected place for medical training.

James Bowen's Family Life

In 1842, James Bowen married Eliza Livingston. She passed away in 1872. In 1874, he married Josephine Oothout. She was the daughter of John Oothout, who was the president of the Bank of New York. Josephine also passed away before him. He then married Athenia Livingston, who was a cousin of his first wife. James Bowen did not have any children from any of his marriages.

General Bowen passed away on September 29, 1886. He died at his home in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. He was known for being a quiet person who loved his home and enjoyed reading.

James Bowen and the Erie Railroad

Becoming President of Erie Railroad

James Bowen was the Vice-President and Treasurer of the New York and Erie Railroad. He became president after Eleazar Lord left the position. He was president when the first part of the railroad opened for public use. This was a big moment for the company.

Mr. Bowen was from New York City and was a wealthy man. He was part of important clubs and knew many influential people. He was especially close with General James Watson Webb. General Webb had supported the New York and Erie project in his newspaper. Because of this friendship, James Bowen joined the company's board. He then became president through Webb's influence.

When Bowen became president, the Erie Railroad seemed to be doing well. Work was moving forward quickly. The Eastern Division was almost finished. It was only a few weeks until trains could run between Piermont and Goshen. A month after Bowen became president, a train ran for the first time between Piermont and Ramapo, which was 20 miles.

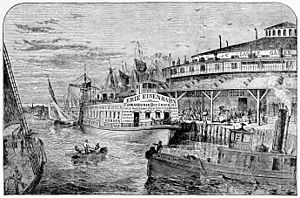

However, there was a problem. The railroad's eastern end was about 25 miles from New York City. People had to take a steamboat between the city and Piermont. Many people started to think that the company would do much better if the railroad reached closer to New York City.

One politician, Francis Granger, pointed out that a railroad that starts 25 miles away from the city it's supposed to connect doesn't seem to be fulfilling its promise. The company's original plan was to connect the coast with the Great Lakes. This would bring trade from the West to New York. So, the fact that the railroad stopped so far from New York City became a big topic of discussion.

A Missed Chance for the Erie Railroad

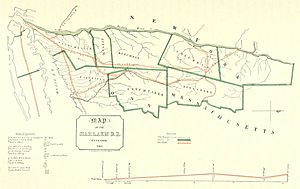

In 1831, the New York and Harlem Railroad Company was formed. It was allowed to build a railway from Twenty-third Street to the Harlem River. Later, it was allowed to extend its tracks to City Hall in New York. In 1836, the company could join with any other railroad company. By 1840, it could extend its railroad from the Harlem River through Westchester County.

In 1841, the New York and Harlem Railroad Company asked the state for financial help. They wanted $350,000 to continue their work. At that time, their railroad was running from City Hall to Fordham, which was 13 miles. They hoped this money would help speed up a rail connection between New York and Albany. But their request was denied.

At this time, the Erie Railroad was very busy building its lines. Eleazar Lord was the president of Erie. Samuel R. Brooks was the president of the New York and Harlem Railroad. Mr. Brooks was a smart man. He saw that the plan for the New York and Albany Railroad was not going well. He also couldn't get money from the state. So, he looked at the Erie Railroad. He realized that joining his railroad with the Erie could save his company and make both much stronger.

There is no clear record of how the Erie management reacted to this idea. But it seems the offer was not accepted. This was a huge missed opportunity. Some historians believe that if the Erie Railroad had joined with the Harlem Railroad, it would have changed the history of railroads in the country. The Erie could have owned valuable land in New York City that later became part of other major railroad systems.

Erie Railroad's Financial Struggles

James Bowen was president from May 1841 to October 1842. For the first six months, the company seemed to be doing well. The Eastern division opened to the public in September, running from Piermont to Goshen. Work on other parts of the railroad was also moving fast.

However, things started to get difficult. Some politicians were against state loans for public projects. Also, the economy was not doing well. It became harder to sell the state bonds that funded the railroad. The price of these bonds dropped. To avoid losing too much money, the company used many bonds as security for short-term loans.

Eventually, the price of the bonds fell even lower. The company had to sell them at a big loss, about $300,000. This meant the company suddenly couldn't pay the interest on its loans in April 1842. Their ability to borrow money was ruined, and their work stopped. The company had to put its affairs in the hands of special managers. These managers protected the company's interests and kept the Eastern division running.

The company owed about $600,000 for work and materials. All construction stopped until 1845. People in the central and western counties were disappointed. They wanted a change in leadership. So, in the autumn of 1843, a new board of directors was chosen. Most of the new directors were from the interior counties, not the city. The old directors, including James Bowen, did not run for re-election. William Maxwell became the new president.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |