James Prescott Joule facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Prescott Joule

FRS FRSE

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 24 December 1818 |

| Died | 11 October 1889 (aged 70) |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | Disproving caloric theory First law of thermodynamics Mechanical equivalent of heat Magnetostriction Joule cycle Joule effect Joule expansion Joule's first law Joule's second law Joule–Thomson effect |

| Spouse(s) |

Amelia Grimes

(m. 1847; died 1854) |

| Children | Benjamin Arthur Alice Amelia Henry |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1852) Copley Medal (1870) Albert Medal (1880) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Influences | John Dalton John Davies |

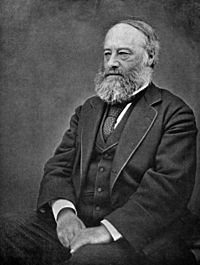

James Prescott Joule (born December 24, 1818 – died October 11, 1889) was a famous English physicist and mathematician. He was born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule also worked as a brewer, managing his family's business.

Joule spent his life studying the nature of heat. He discovered how heat is related to mechanical work. This important discovery led to the law of conservation of energy. This law states that energy cannot be created or destroyed. It can only change from one form to another. His work also helped develop the first law of thermodynamics.

The SI derived unit of energy, the joule, is named after him. This unit measures energy and work. He also worked with Lord Kelvin to create a temperature scale. This scale is now known as the Kelvin scale. Joule also studied magnetostriction, which is how magnetic fields can change the shape of materials. He found the relationship between electric current and the heat it produces. This is called Joule's first law. He published his first experiments on energy changes in 1843.

Contents

Early Life and Discoveries

James Joule was born in 1818. His father, Benjamin Joule, was a rich brewer. James was tutored by the famous scientist John Dalton. He was also influenced by chemist William Henry.

Joule was very interested in electricity. He and his brother even experimented by giving each other electric shocks! As an adult, he managed the family brewery. Science was his serious hobby.

Electricity and Heat

Around 1840, Joule started looking into replacing the brewery's steam engines. He wanted to use the new electric motors instead. He wrote his first scientific papers about this for Annals of Electricity.

Joule wanted to know which machine was more efficient. He discovered Joule's first law in 1841. This law says that the heat produced by an electric current is related to the strength of the current and the resistance it meets.

He realized that burning coal in a steam engine was cheaper than using expensive zinc in an electric battery. Joule measured the output of these methods. He used a standard unit called the "foot-pound." This unit measures the ability to lift a one-pound weight one foot high.

Challenging Old Ideas

Joule's interest grew beyond just money. He wanted to know how much work could come from a certain energy source. In 1843, he showed that the heat he measured came from the conductor itself. It was not transferred from other parts of the equipment.

This challenged the caloric theory. This old theory said that heat could not be created or destroyed. It had been the main idea about heat since 1783. Joule was a young scientist working outside universities. So, it was hard for him to convince others.

The Mechanical Equivalent of Heat

Joule continued his experiments with his electric motor. He estimated the mechanical equivalent of heat. This is the amount of mechanical work needed to produce a certain amount of heat. He found that about 4.1868 joules of work were needed to raise the temperature of one gram of water by one Kelvin.

He shared his findings in 1843. But his ideas were not well received at first.

More Experiments

Joule was not discouraged. He looked for a way to show that work could be turned into heat using only mechanical means. He forced water through a cylinder with holes. He measured the small amount of heat produced by the water's stickiness (viscosity). He got a similar value for the mechanical equivalent of heat.

The fact that his electrical and mechanical experiments gave similar results was strong proof for Joule. It showed that work could indeed be turned into heat.

Joule tried a third method. He measured the heat made when compressing a gas. He got another similar value. He presented his paper to the Royal Society in 1844. However, they did not publish it. He had to publish it in the Philosophical Magazine in 1845.

The Paddle Wheel Experiment

In June 1845, Joule presented his most famous experiment. He used a falling weight to spin a paddle wheel in an insulated barrel of water. The falling weight did mechanical work. This work made the water warmer.

He estimated the mechanical equivalent of heat again. In 1850, Joule published an even more precise measurement. This value was very close to what scientists accept today.

Kinetic Theory and Heat

Kinetics is the study of motion. Joule was a student of John Dalton. He strongly believed in the atomic theory. This theory says that everything is made of tiny particles called atoms. Many scientists at the time were still unsure about atoms.

Joule understood how his discoveries related to the kinetic theory of heat. This theory says that heat is caused by the movement of tiny particles. His notes show he thought heat was a form of spinning motion.

Joule also looked at the work of earlier scientists. He found ideas similar to his own in the writings of Francis Bacon and Sir Isaac Newton. He also saw connections to the work of Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford) and Sir Humphry Davy.

Honours and Legacy

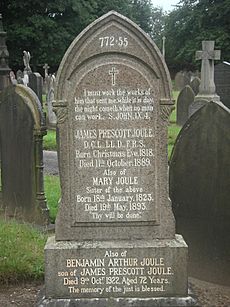

James Joule passed away at his home in Sale in 1889. He is buried in Brooklands cemetery there. His gravestone has the number "772.55" on it. This number represents his important measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat from 1878. It means that 772.55 foot-pounds of work are needed to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit.

Joule received many awards and honors for his scientific work:

- He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1850.

- He won the Royal Medal in 1852 for his work on the mechanical equivalent of heat.

- He received the Copley Medal in 1870 for his experiments on the theory of heat.

- He was President of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1860.

- He was President of the British Science Association twice (1872, 1887).

- He received honorary degrees from several universities.

- In 1878, he received a special pension of £200 per year for his services to science.

- He was awarded the Albert Medal in 1880. This was for showing the true relationship between heat, electricity, and mechanical work.

There is a memorial to Joule in Westminster Abbey. A statue of him stands in Manchester Town Hall, next to a statue of John Dalton.

Family Life

In 1847, James Joule married Amelia Grimes. Sadly, Amelia passed away in 1854, just seven years after they were married. They had three children together: a son named Benjamin Arthur (born 1850), a daughter named Alice Amelia (born 1852), and another son named Joe (born 1854), who sadly died very young.

Joule was very proud of his children, Alice and Benjamin. When James died in 1889, Alice and Benjamin were very sad. Alice passed away ten years later. Benjamin later found a wife and married. He lived until 1922.

Published Work

- Joule, J.P. (1841). "On the Heat evolved by Metallic Conductors of Electricity, and in the Cells of a Battery during Electrolysis". Philosophical Magazine.

- Joule, J.P. (1843). "On the Calorific Effects of Magneto-Electricity, and on the Mechanical Value of Heat". Philosophical Magazine.

- Joule, J.P. (1844). "On the Changes of Temperature Produced by the Rarefaction and Condensation of Air". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.

- Joule, J.P. (1845). "On the Changes of Temperature Produced by the Rarefaction and Condensation of Air". Philosophical Magazine.

- Joule, J.P. (1845). "On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat". Notices and Abstracts of Communications to the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Joule, J.P. (1845). "On the Existence of an Equivalent Relation between Heat and the ordinary Forms of Mechanical Power". Philosophical Magazine.

- Joule, J.P. (1850). "On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.

- Joule, J. P. (1884). The Scientific Papers of James Prescott Joule. London: Physical Society.

- Joule, J. P. (1887). Joint scientific papers. London: Taylor and Francis.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: James Prescott Joule para niños

In Spanish: James Prescott Joule para niños

- Latent heat

- Sensible heat

- Internal energy