Jessie Oonark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

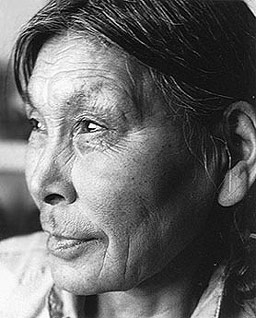

Jessie Oonark

OC RCA

|

|

|---|---|

| Una Unaaq |

|

|

|

| Born | April 1906 |

| Died | March 7, 1985 (aged 78) Churchill, Manitoba

|

| Known for | Inuit graphic artist, fabric artist |

|

Notable work

|

Woman (1970) Big Woman |

| Movement | Contemporary (post-1949) period of Inuit art |

| Spouse(s) | Qabluunaq, (Kabloona) son of Naatak and Nanuqluq |

Jessie Oonark, OC RCA (ᔨᐊᓯ ᐅᓈᖅ; born March 2, 1906 – died March 7, 1985) was a very talented and important Inuit artist. She was part of the Utkuhihalingmiut people. Jessie Oonark created many beautiful wall hangings, prints, and drawings. Her artwork is now kept in major collections, including the National Gallery of Canada.

Contents

Early Life and Traditional Ways

Jessie Oonark was born in 1906 near Chantrey Inlet in what is now Nunavut. This area was the traditional home of the Utkukhalingmiut people. Her art often shows what life was like when she lived as a hunter and nomad for over 50 years.

Her family moved between fishing camps near the Back River and caribou hunting camps near Garry Lake. They lived in snow houses (igloos) in winter and caribou skin tents in summer. Jessie learned early how to prepare animal skins and sew warm caribou clothing. They mostly ate fish like trout and Arctic char, along with barren-ground caribou.

Some important tools and clothes that often appeared in her art were the ulu (a woman's knife), kamik (traditional boots), and amauti (a parka for carrying a baby). Even though she started making art when she was 54, she became a very active and famous artist in the next 19 years.

Language and Stories

Jessie Oonark spoke the Utkuhiksalingmiut language fluently. This language is a special dialect of Netsilik Inuit. Like other early Inuit artists from her area, Jessie's art was deeply connected to the oral stories and legends of the Utkuhiksalingmiut people. These stories were a big part of her culture.

Her Family and Challenges

Jessie Oonark's parents were Qiliikvuq and Aghlquarq. Her father and his brothers hunted muskox. Jessie spent most of her early life in Chantrey Inlet, where there was plenty of fish.

The Utkukhalingmiut people had many rules, called taboos. One rule was against drawing pictures. A researcher named Marie Bouchard said that Jessie's grandmother often warned her that drawings could come to life at night!

Jessie married Qabluunaq when she was young. He was a good hunter, but her family often faced hunger. Her oldest daughter, Janet Kigusiuq, remembered these hard times. Her grandmother would even boil caribou skin to make a "broth" to help with hunger.

"My grandmother, Natak, was always cooking something. She used to cook caribou skins. She would take hair off the skin and cook it. We would drink the broth. My grandmother used to even cook wolf meat. That was how we survived."

—Janet Kigusiuq to Marie Bouchard

Jessie had twelve children, including famous artists like Janet Kigusiuq, Mamnguqsualuq, Victoria Mamnguqsualuq, Miriam Nanuqluq, Nancy Pukingnaq, and William Noah.

In the 1940s, the Canadian government gave Inuit people special identification numbers on discs. Jessie Oonark was given the number E2-384. These disc numbers were stopped in the 1960s.

Around 1953 or 1954, Jessie's husband and four of her youngest children sadly died from an illness.

A Time of Hunger

In the 1950s, the caribou changed their migration path. This meant many Inuit, including Jessie and her family, faced severe hunger. The winter of 1957–1958 was especially tough. Jessie's son, William Noah, walked to Baker Lake to get help. The Canadian armed forces then flew Jessie and her daughter Nancy to Baker Lake.

Life in Baker Lake

When Jessie arrived in Baker Lake in 1958, she worked hard to survive. She cleaned skins, cooked, washed dishes, and sewed traditional Arctic clothes to sell. She also worked as a janitor at the Anglican Church.

In the 1950s, many Inuit moved to Baker Lake because of the famine. The government opened a school and built houses there. Officials encouraged Inuit people to develop arts and crafts to help them earn money.

Becoming an Artist

In 1958, Jessie saw some school children drawing in Baker Lake. She told the teacher that she could draw better than them! The next year, a biologist named Dr. Andrew Macpherson heard this. He gave Jessie colored pencils and paper. He bought her drawings and took some to Ottawa. He kept sending her art supplies.

In 1960, Jessie sent him twelve finished drawings. Some of her drawings were sent to James Archibald Houston at the West Baffin Co-operative in Cape Dorset. Two of her drawings were made into stone cut prints for the 1960 Cape Dorset print collection. This was the first time art from an Inuk outside Cape Dorset was included.

In 1961, the government started an arts and crafts program, and Jessie Oonark became one of their main artists. In 1963, a printmaking program began in Baker Lake. Jessie's drawings were used for some of the first experimental prints.

In 1966, Boris Kotelewetz, an arts officer, gave Jessie a studio space and a salary. By 1969, Jessie was already a very skilled artist. That year, she made a large wall hanging that is now in the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly in Yellowknife.

In 1970, the first Baker Lake Print Collection was released. Jessie's drawing "Woman" (1970) was featured on the cover. She continued to create images for the Baker Lake Print collections until 1985.

The Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa organized a traveling exhibition of 50 of Jessie's drawings in 1970. Later that year, she had her first solo exhibition in Toronto.

In 1971, the Baker Lake Sanavik Co-operative was formed. This co-op helped printmakers turn Jessie's drawings into beautiful art prints. Jessie also received a grant to travel to Toronto and Montreal for her art exhibition openings.

Her work was used to illustrate a book of Inuit poetry in 1972. In 1975, Jessie Oonark was chosen as a Member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Her art was even featured on two stamps for the United Nations in 1976!

In 1984, she was made an Officer of the Order of Canada, which is a very high honor.

After she passed away, the Winnipeg Art Gallery held a special exhibition of her work in 1986. By 1987, Jessie Oonark had already had many solo and group exhibitions around the world.

Her art continues to be celebrated. In 2015, one of her wall hangings sold for $70,800, setting a new record for her work.

Artistic Style and Themes

Jessie Oonark's art has a strong, bold, and clear style. She often used bright colors and interesting shapes.

Visual Tricks in Art

Jessie Oonark's art often has "visual puns" or Ambiguous images. This means her drawings can look like different things depending on how you view them. For example, her work "Two Fish Looking for Something to Eat" (1978) can look like two fish swimming or a standing woman. She liked to make her art have more than one meaning.

"These are sea creatures, and they are sort of eating one another. There is a story, and that is it that one whole person along with a qayak was swallowed up by some giant fish or creature or whatever – somewhere near Gjoa Haven or Back River."

—Oonark in Jackson 1983:39

Shamanism and Spirits

Jessie Oonark's father and grandfather were said to be shamans, who were spiritual healers. Even though Jessie became Anglican, she still showed shamans and spirits in her art. For example, in "Horned Spirits" (1970) and "A Shaman's Helping Spirits" (1971).

"It was small and wore a baby caribou-skin hat. They asked me if I wanted to have it. I saw it from a distance and it almost came near me, but I didn't want to have a spirit helper."

—Jessie Oonark in Bouochard 1987

Drum Dance and Stories

Jessie also drew images of the traditional drum dance, even though she no longer participated. She often drew scenes from Inuit stories and legends, like the famous Kiviuq story. Her parents and mother-in-law were great storytellers, and these tales inspired her art.

Clothing and Tools

Jessie Oonark often featured traditional Inuit clothing and tools in her work. The ulu (woman's knife) and amauti (parka) were common themes. Her famous print "Woman" (1970) shows a woman in her winter dress, highlighting the beautiful design of caribou skin clothing.

Birds and Nature

Birds often appear in Jessie's art. They can symbolize flight, shamanism, or the arrival of spring and new life.

Christianity in Art

Jessie Oonark also included Christian themes in her art, especially after befriending Elizabeth Whitton, the Anglican minister's wife in Baker Lake. Jessie drew pictures of the church, the minister, and local people with traditional Inuit tattoos. She blended traditional Inuit clothing and symbols with Christian ideas in her artwork.

Jessie Oonark's Impact

Jessie Oonark, along with other artists like Pitseolak Ashoona and Kenojuak Ashevak, quickly became very important figures in Inuit art. Many people believe that without Jessie Oonark's amazing talent, Baker Lake might not have become such a well-known center for art prints.

Her influence continues today. All of her children became artists, carrying on her creative legacy.

Collections

Jessie Oonark's artwork is held in many major collections around the world. Some of these include:

- National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa, ON)

- Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto, ON)

- Canadian Museum of History (Hull, QC)

- Winnipeg Art Gallery (Winnipeg, MB)

- Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montréal, QC)

- Glenbow Museum (Calgary, AB)

- Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen's University (Kingston, ON)

- Dennos Museum Center, Northwestern Michigan College (Traverse City, Michigan)

One of her largest artworks, an untitled wall hanging from 1973, is displayed in the main lobby of the National Arts Centre in Ottawa.

Later Life

In 1979, Jessie Oonark began to experience numbness in her hands and feet. This made it hard for her to draw and create art. She made only a few more pieces after that. Her art career lasted about 19 years, but her impact on Inuit art was huge.

Jessie Oonark passed away on March 7, 1985, in Churchill, Manitoba. She is buried in Baker Lake.

Images for kids

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |