Joan, Countess of Flanders facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Joan |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Countess of Flanders and Hainaut | |

| Reign | 1205–1244 |

| Predecessor | Baldwin IX and VI |

| Successor | Margaret II and I |

| Born | c. 1199 |

| Died | 5 December 1244 (aged 44–45) Abbey of Marquette, Marquette-lez-Lille |

| Spouse | Ferdinand of Portugal (m. 1212; d. 1233) Thomas of Savoy (m. 1237) |

| House | House of Flanders |

| Father | Baldwin I, Latin Emperor |

| Mother | Marie of Champagne |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Joan, also known as Joan of Constantinople (born around 1199 – died 5 December 1244), was a powerful ruler. She was the Countess of Flanders and Hainaut from 1205 until her death. She became a countess at just six years old!

Joan was the older daughter of Baldwin IX, who was the Count of Flanders and Hainaut, and Marie of Champagne. She became an orphan during the Fourth Crusade. King Philip II of France raised her in Paris. He arranged her marriage to Ferdinand of Portugal in 1212.

Ferdinand soon turned against King Philip. This led to a war that ended with the defeat at Bouvines. Ferdinand was captured and imprisoned. Joan then ruled her lands alone from the age of 14. She faced challenges from her younger sister, Margaret. She also dealt with a rebellion led by a man who claimed to be her father.

After the war, Ferdinand was released but died soon after. Joan then married Thomas of Savoy. She passed away in 1244 at the Abbey of Marquette near Lille. She had outlived her only child, a daughter she had with Ferdinand.

Joan was a smart ruler who helped her lands grow. She gave special rights to cities, which helped their economies. She also supported new religious groups like the Mendicant orders and the Beguines. During her time, many women's religious groups were started. This changed the role of women in society and the church.

Some famous stories were written for Joan. These include parts of the Story of the Grail and the Life of St. Martha. The first novel written in Dutch, Van den vos Reynaerde, was also created by someone in her court. You can still see paintings and statues of Joan in France and Belgium today.

Contents

Joan's Early Life and Challenges

Becoming a Countess at a Young Age

We don't know the exact date Joan was born. Records show that she and her younger sister, Margaret, were baptized in the Church of St. John in Valenciennes.

In 1202, Joan's father, Baldwin IX, left his lands to join the Fourth Crusade. After capturing Constantinople, he became emperor in May 1204. Joan's mother, Marie of Champagne, decided to join him. She left Joan and Margaret with their uncle, Philip I of Namur. Sadly, Marie died in August 1204 in Acre, Israel. A year later, in April 1205, Baldwin disappeared during a battle. His fate is still unknown.

When news of Baldwin's disappearance reached Flanders in February 1206, Joan became the Countess of Flanders and Hainaut. She was still a child, so a group of trusted people managed her lands for her.

Growing Up in Paris

Joan's uncle, Philip, was in charge of her and Margaret. He soon made a deal with King Philip II of France. He gave the French king control over Joan and Margaret's upbringing. They grew up in Paris alongside other young nobles.

In 1206, the French king wanted to make sure Philip wouldn't marry off his nieces without his permission. They agreed that Joan and Margaret couldn't marry before they were adults without the Marquis of Namur's consent. But the Marquis also couldn't stop the king's choice of husbands.

In 1211, a nobleman named Enguerrand III of Coucy offered a lot of money to marry Joan. His brother would marry Margaret. But the nobles in Flanders didn't like this idea. Instead, Matilda of Portugal suggested her nephew, Ferdinand of Portugal, as Joan's husband. Joan and Ferdinand were married in Paris in January 1212. Ferdinand then became Joan's co-ruler.

Early Challenges as a Ruler

On their way to Flanders, Joan and Ferdinand were captured by Joan's cousin, Louis of France. Louis wanted to get back lands that he felt belonged to his late mother.

Joan and Ferdinand were freed only after signing the Treaty of Pont-à-Vendin in February 1212. They had to give up the towns of Aire-sur-la-Lys and Saint-Omer to France. After this, Joan and Ferdinand joined an alliance with King John of England and Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor. They also gained the support of the powerful people of Ghent.

In response, King Philip II attacked Lille in 1213, burning most of it. At the Battle of Bouvines in July 1214, Ferdinand was captured. He remained a prisoner of the French for twelve years. During this time, Joan ruled alone.

One of her first decisions was to remove taxes for certain groups to help businesses grow. For example, settlers in Kortrijk didn't have to pay property tax. This helped the wool weaving industry there. She also ordered Lille's walls to be rebuilt. But fearing another French attack, she signed the Treaty of Paris in October 1214. This treaty meant that major forts in southern Flanders were destroyed. It also meant Flanders was largely controlled by Paris.

Meanwhile, Joan tried to get her marriage annulled. She argued it was never fully completed. In 1221, she wanted to marry Peter Mauclerc, but King Philip II refused.

Sisterly Conflict and a False Father

Before July 1212, Joan's younger sister Margaret married Bouchard of Avesnes. The French King told Pope Innocent III that Bouchard had already taken holy orders as a sub-deacon. In 1215, the Pope canceled the marriage. But Margaret and Bouchard refused to separate. They had three sons together.

In 1219, Bouchard was captured during a battle against Joan in Flanders. He was released two years later after agreeing to separate from Margaret. Between August and November 1223, Margaret married William II of Dampierre.

Another problem for Joan happened in 1224. She wanted to take control of the castle of Bruges. King Philip II had given it to John of Nesle. Joan argued that the bailiff was asking for too much money. The dispute went to King Louis VIII of France. He sided with John of Nesle, which was another setback for Joan.

The Impostor Claiming to be Baldwin IX

In 1225, a hermit living near Mortagne-du-Nord claimed to be Joan's father, Baldwin IX. He said he had escaped from the Bulgarians after twenty years. He demanded that Joan return his rights to Flanders and Hainaut.

The supposed Baldwin acted like a real count. Many nobles and cities, including Lille and Valenciennes, supported him. Even King Henry III of England offered to ally with him against Louis VIII. Joan sent her advisor, Arnold of Oudenarde, to meet the hermit. Arnold returned convinced that the man was truly Baldwin IX. Other people were doubtful, but they were accused of being bribed by Joan.

Joan was forced to hide in Mons, the only city that stayed loyal to her. King Louis VIII agreed to help Joan get her lands back, but he demanded a high price. Joan had to pay 20,000 livres and give up the cities of Douai and Lécluse as a promise.

Before fighting, Louis VIII sent his aunt, Sybille of Hainaut, to meet the hermit. She had doubts about his identity. On May 30, 1225, the King met the hermit and questioned him. The hermit couldn't remember important details about Baldwin IX's life, like when he was knighted or his wedding night. Bishops recognized him as a trickster who had tried to pretend to be someone else before.

Convinced he was an impostor, Louis VIII gave him three days to leave. The false Baldwin IX fled but was caught near Besançon. He was sent to Joan. Despite a promise to spare his life, he was executed. It's thought that Bouchard of Avesnes, Margaret's former husband, might have been behind this plot.

After taking back the rebellious cities, Joan made them pay large fines. This allowed her to pay off her debts to the King of France much faster than planned. It also helped her pay the ransom for her husband, Ferrand.

Ferrand's Release and Joan's Second Marriage

Joan tried again to marry Peter Mauclerc. She asked Pope Honorius III to cancel her marriage to Ferrand due to family ties, and the Pope agreed. However, King Louis VIII refused to allow her to marry Mauclerc. He worried that his kingdom would be too squeezed between their lands. To stop Joan's marriage plans, the French King got the Pope to renew her marriage with Ferrand. He also forced Joan to agree to a treaty and pay a ransom for her imprisoned husband.

In April 1226, Joan and Louis VIII signed the Treaty of Melun. Ferrand's ransom was set at 50,000 livres parisis. The cities of Lille, Douai, and Lécluse were given to France as a promise until the full amount was paid. Joan also had to stay married to Ferrand. Both Joan and Ferrand could be excommunicated if they betrayed the King. Many cities and nobles also had to promise loyalty to the King of France. After Louis VIII died, his wife Blanche of Castile and son Louis IX finally released Ferrand in January 1227. Joan paid half the ransom, which was reduced to 25,000 livres.

In late 1227 or early 1228, Joan gave birth to a daughter named Marie. A few years later, on July 27, 1233, Ferrand died. He had suffered from kidney stones since his capture. His body was buried in the Abbey of Marquette-lez-Lille. After Ferrand's death, Joan wanted to marry Simon de Montfort, but King Louis IX refused because Simon was loyal to England.

After Ferdinand's death, their daughter Marie, who was Joan's heir, was sent to Paris for her education. In June 1235, she was promised in marriage to Robert, Louis IX's brother. Sadly, Marie died shortly after, leaving Joan without children.

Following a suggestion from Blanche of Castile, Joan agreed to marry Thomas of Savoy. He was the uncle of Louis IX's wife. They married on April 2, 1237. For this marriage, Joan had to pay 30,000 livres to the King of France and promise her loyalty again.

Joan died on December 5, 1244, at the Abbey of Marquette-lez-Lille near Lille. She had become a nun there shortly before. She was buried next to her first husband. Since she had no surviving children, her sister Margaret became the next ruler. Her tomb was found in 2005, but her remains were not inside it.

Joan's Impact as a Ruler

Boosting the Economy

Countess Joan helped the cities in Flanders grow, especially in her early years of ruling (1214–1226). She gave special legal and tax benefits to cities like Dunkirk, Ghent, Lille, and Ypres. In Kortrijk, in 1217, she encouraged workers to move there for the wool industry. She did this by removing a tax for new settlers.

After her husband Ferrand returned, she continued this policy. She gave new benefits to cities like Douai, Ghent, and Ypres. These benefits gave them more freedom from the countess's power. After Ferrand died in 1233, she kept the Lille Charter. She also allowed Valenciennes to build a belfry.

After marrying Thomas of Savoy (1237–1244), she continued to help the economy. She offered tax breaks and improved the justice system. She also took steps to help river and sea trade in cities like Bruges and Damme. In less urban areas, especially in Hainaut, her power remained strong. Joan always worked to help the economy and give cities more freedom. This was because she needed the support of the wealthy city dwellers against the King of France.

To help river trade, Joan ordered the building of water gates in Menen and Harelbeke in 1237. This made the Leie river easier to travel on. In 1242, she allowed the leaders of Lille to create three locks to connect to the Deûle river.

Supporting Religion

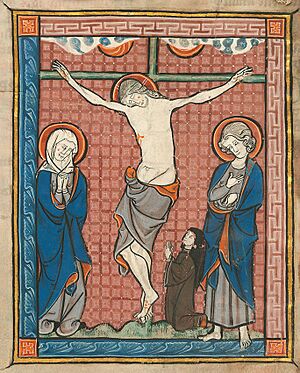

Joan had good relationships with the Cistercians. She founded the Abbey of Marquette-lez-Lille. She also supported or helped start several other monasteries for Cistercian nuns. Before the 12th century, monasteries in Flanders and Hainaut were only for men. But during the 13th century, twenty female monasteries were founded in Flanders and five in Hainaut. Joan and her sister Margaret supported these.

Joan also helped start Mendicant orders in her lands. In Valenciennes, she gave Franciscans an old castle to build a convent. She even sent her builders to help construct the church and convent for the Franciscans in Lille.

The Countess also helped establish many monasteries and Béguinages (communities for religious women). The most famous ones were in Mons and Valenciennes (Hainaut), and Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres (Flanders). These were all founded between 1236 and 1244. Her sister Margaret founded others in Douai and Lille in 1245.

By the end of the 12th century, the religious Victorines were present in Flanders and Hainaut. Joan encouraged this movement. In 1244, she directly supported the creation of the Bethlehem Priory in Mesvin. These monasteries had a lot of freedom and helped people in need. They also fit well with the new ways women were expressing their faith in the 13th century.

Joan also supported hospitals, including Saint-Sauveur and Saint-Nicolas in Lille. In 1228, she and Ferrand helped found the Biloke in Ghent. In February 1237, she founded the Hospice Comtesse. For this, she gave the gardens of her home in Lille. She also founded the Hospital of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary in Valenciennes. This hospital was used by the beguines.

Joan's Influence on Medieval Stories

Two old books are thought to have belonged to Joan. One is a Psalter (a book of Psalms) from around 1210. It might have been a gift to her when she married Ferdinand. The second is a copy of the Story of the Grail, from 1210 to 1220. Joan might have added more stories to this book.

The Story of the Grail is strongly connected to the Counts of Flanders. Chrétien de Troyes wrote under the protection of Joan's great-uncle. Manessier, who wrote the Third continuation of the story, dedicated his work to Joan. It's likely that Wauchier de Denain, who wrote the Second continuation, was also part of her court. He definitely dedicated his Life of St. Martha to Joan around 1212. This story was meant to teach and inspire her.

The Van den vos Reynaerde is the first version of Reynard the Fox in Dutch. It has unique parts not found in other versions. The author, "Willem die Madocke maecte," was a lay Cistercian monk. Joan asked the Cistercian General Chapter to recruit him in 1238. He became the director of the Hospice Comtesse in Lille.

However, Joan's role in supporting writers seems to have been limited. It's possible that to succeed in a world mostly run by men, she chose not to focus on this role, which was often given to women.

Joan's Legacy

Later historians often wrote negatively about Joan. Many believed that the hermit was truly Baldwin IX. They thought Joan had committed a terrible crime by killing him. In the mid-1400s, a book called Baudouin, Count of Flanders even said Joan was an illegitimate child possessed by a demon.

In the 1800s, some writers repeated the idea that Joan killed her father. But then, Emile Gachet began to defend Joan's reputation. Later, in 1840, Jules de Saint-Genois wrote A false Baudouin. The next year, Edward le Glay published his Histoire de Jeanne de Constantinople. This book helped to clear Joan's name and became a key source on her life.

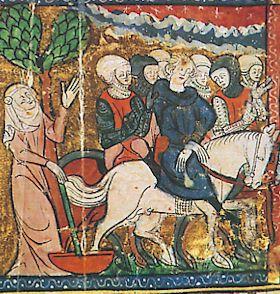

The Museum of the Hospice Comtesse has two tapestries showing Countess Joan. One shows her sitting between her two husbands, Ferdinand and Thomas. The other shows Count Baldwin IX with his wife and two daughters, Joan and Margaret. In the same museum, a painting from 1632 shows Countesses Joan and Margaret with religious figures.

There are statues of Joan in the béguinage of Kortrijk and the Old Saint Elisabeth in Ghent. The mother-child hospital in Lille is named after her. The city of Wattrelos has created large parade figures (Géants du Nord) for Joan and her two husbands. The city of Marquette-lez-Lille, where Joan was buried, also has these figures.

In 2009, an exhibition called Joan of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders and Hainaut was held. It included art dedicated to Joan and Margaret.

See also

In Spanish: Juana de Constantinopla para niños

In Spanish: Juana de Constantinopla para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |