John of Gaunt's chevauchée of 1373 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chevauchée of John of Gaunt (1373)Grande chevauchée |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Hundred Years' War | |||||||

Late 15th century portrait of John of Gaunt, also depicting his coat of arms |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,000 | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6,000 killed or captured | Unknown | ||||||

The John of Gaunt's chevauchée of 1373 was a long military raid by English forces during the Hundred Years' War. John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, led this journey. It started in Calais, France, in August 1373 and ended in Bordeaux in December 1373.

This "chevauchée" (which means a mounted raid) covered more than 1,500 kilometers (about 930 miles). It was the longest such raid the English ever organized in France. Even though it caused a lot of damage, it was a big failure for England. They gained little military or political advantage and suffered huge losses.

Contents

Why This Journey Happened

War Between England and France

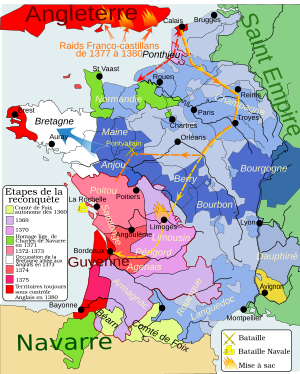

The war between England and France, known as the Hundred Years' War, had started again in 1369. Charles V of France, the French king, was very clever. He worked hard to take back lands England controlled in France. At this time, the English king, Edward III, was facing many defeats.

England only held a few areas in France. These included Calais, parts of Brittany, the Atlantic coast south of the Gironde estuary, and the area around Angoulême.

Who Was John of Gaunt?

John of Gaunt was King Edward III's second son. He was born in 1340. He had recently lost his wife, Blanche of Lancaster. From her, he inherited the duchy of Lancaster, which made him one of the richest landowners in England. People said he was a brave fighter. However, he was not as skilled as his older brother, Edward the Black Prince. In 1369, John of Gaunt had already led a disappointing raid through northern France.

The Original Plan and Why It Changed

By late 1372, the English Parliament agreed to send a strong army of 4,000 men. John of Gaunt was chosen to lead them. The first plan was for him to land in Brittany. He would help John IV of Brittany regain control there. Then, he would cross the Loire river at Nantes and enter Aquitaine.

However, in early 1373, England's situation in Brittany got much worse. The French took back Nantes. This ruined Gaunt's plan to cross the Loire there. Only three places in Brittany remained friendly to England. These were Derval, Brest, and Auray. Because of this, the path to Aquitaine was blocked. The plan was changed in May. Also, the English navy was too weak to sail directly across the Bay of Biscay. The only choice left was to land at Calais and march around Paris to the east.

How the English Fought

The "Chevauchée" Tactic

When Charles V became king, he tried to avoid big battles. He wanted to protect his knights. In response, the English used a tactic called the "chevauchée." The main goal of a chevauchée was to destroy the countryside.

English armies would spread out and loot farms. They burned crops and destroyed buildings. They lived off the land they raided. They would attack towns that refused to pay them. King Edward III first used this method in 1346. His son, the Black Prince, improved it in 1355 and 1356.

French Counter-Tactics

King Charles V and his top general, Bertrand du Guesclin, developed a way to fight back. They told people to go inside strong castles and fortified cities. They brought their food and animals with them. Anything that could not be protected was destroyed. French soldiers stayed inside castles. Mobile French troops would harass the English columns. They would also cut off their supplies. This meant the English had to march through burned lands, surrounded by strong French forts.

The Great Ride

Starting from Calais

Even though the plan changed, and John of Brittany wasn't thrilled about the new route, he joined forces with John of Gaunt. The Earl of Salisbury was sent by sea to help English forces in Brest.

John of Gaunt's army landed at Calais in early July 1373. By August 9, a fleet of over a hundred ships brought more soldiers. The army had 6,000 archers and 3,000 men-at-arms. This included 1,800 Scottish soldiers. About 2,000 non-fighting people also came along. The main commanders were Edward Despenser, Thomas Beauchamp, and William Ufford. Many English nobles and captains were also part of the army.

Marching Around Paris

In August, the English army left Calais. They split into two groups. John of Brittany's group marched south. John of Gaunt's group marched further east. They passed by towns that were friendly to them. On their first night, the English camp stretched for miles.

The army moved about ten kilometers (6 miles) each day. They looted and burned everything in a 20-kilometer (12-mile) wide path. The fastest troops marched first. Then came the two Dukes. Supply wagons followed them. Finally, the main army closed the march. They spread out to find enough food. But this also made them open to attacks from French cavalry or even angry farmers.

Over the next few days, the English fought French soldiers in northern France. A fierce fight happened near Doullens, which the English almost captured. Around August 19, the two Dukes met up. John of Gaunt had tried and failed to take Bray-sur-Somme.

Meanwhile, in Amiens, the French army was getting stronger. King Charles V called in more soldiers, including Bertrand du Guesclin. French soldiers attacked a small English group near Ribemont-sur-Ancre. They defeated them. The English continued their destructive path, setting Roye on fire.

Around September 3, the Dukes stayed near Laon for three days. Their troops looted the countryside. The 1,800 French soldiers in Laon did not stop them. Then, the army headed to Soissons. About 2,400 French soldiers followed them closely. These French soldiers avoided big battles. They told civilians to hide in cities. They moved animals to safety. They left soldiers in forts and destroyed bridges. This made it harder for the English to move and helped guide them.

The land of Coucy was not attacked. Its lord, Enguerrand VII de Coucy, was married to King Edward III's daughter. He tried to stay neutral.

On September 9, 1373, the French attacked an isolated English group at Oulchy. They killed many men and captured several knights. But no other major fights happened. The English stayed together, and the French followed King Charles V's orders.

More French troops arrived. The Duke of Orléans came with the "army of the sea." While John of Gaunt and John of Brittany were raiding the Champagne region, Du Guesclin headed east. He talked with the king in Paris. So, when the English reached Troyes around September 22, Du Guesclin and other French leaders were waiting. They had over 7,000 men. This position was important. It stopped the English from marching on Paris or Brittany. The English left Troyes around September 25.

A writer named Froissart wrote about this time:

This is how the Duke of Lancaster and the Duke of Brittany rode in the kingdom of France, and led their men ; never did they find anyone to talk to in matter of battle [...] ; they often sent their heralds to the lords who were pursuing them, looking for battle [...] ; but never did the French want to accept.

Marching South

The two Dukes then went along the Seine river. They crossed it near Gyé-sur-Seine around the end of September. Then they headed south into the Nivernais region.

The French army followed them in two groups. They marched on either side of the English, about an hour's walk away. The French soldiers slept in castles or fortified cities. The English, however, had to camp outdoors every night.

Around October 10, the English crossed the Loire river at Marcigny. They left a path of destruction behind them. Crossing the Allier river was harder. John of Gaunt had to go north-west towards Moulins. Its old stone bridge was one of the few ways to cross the river. He almost got captured there. French forces were all around him. The English barely escaped, but they had to leave many supply wagons behind.

As winter approached, the situation got worse. The countryside was poorer. In early November, some French troops left. The Marshal of Sancerre took charge of the remaining French operations.

In the Combrailles region and Upper Limousin, John of Gaunt's soldiers faced a very harsh winter. The thick forests were cold and almost empty. There was little food for horses or men. Cold and heavy rain turned roads into swamps. French horsemen harassed the English. The English left a long trail of horses that had died from starvation.

Finally, in early December 1373, the Duke of Lancaster reached the Corrèze river valley. This area was still against the French king. He was able to rest there for three weeks.

What Happened After

Unlike his older brother, Edward the Black Prince, who returned from his 1355 raid with huge amounts of treasure, John of Gaunt arrived in Bordeaux in late 1373 with a much smaller army. It was a bitter defeat. No big battles had happened, but half of his 30,000 horses had died. Two-thirds of the wagons had to be left behind. About 3,000 men died from cold, sickness, or hunger. Another 3,000 were killed or captured by the French. Many who made it to Bordeaux died later from illnesses caught during the journey.

In Bordeaux, things were very bad. The remaining soldiers doubled the town's population. A terrible sickness, the bubonic plague, spread that winter. Some knights were even begging for food. Money from London to pay the troops did not arrive. John of Gaunt's army was sick, sad, and many soldiers had left. John IV of Brittany sailed back to his duchy with a thousand men. By late March 1374, Lancaster had to give up his plan to invade Castile, which was allied with France. On April 8, 1374, he left for England.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |