José María Melo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

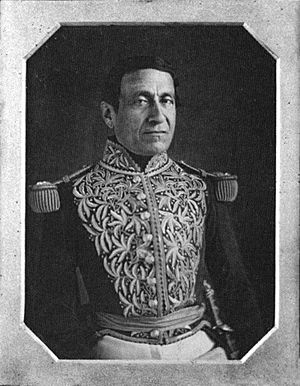

José María Dionisio Melo y Ortiz

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 7th President of the Republic of New Granada | |

| In office April 17, 1854 – December 4, 1854 |

|

| Preceded by | José María Obando |

| Succeeded by | José de Obaldía (as interim president) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 9, 1800 Chaparral, Tolima, Viceroyalty of New Granada |

| Died | June 1, 1860 La Trinitaria, Chiapas, Mexico |

| Political party | Liberal (Draconian) |

| Spouses | Teresa de Vargas París Juliana Granados |

José María Dionisio Melo y Ortiz (born October 9, 1800 – died June 1, 1860) was a Colombian general and important political leader. He fought bravely in the wars that made South America independent from Spain. In 1854, he became the president of Colombia for a short time.

Melo was of Pijao ancestry, making him the first and only president of Colombia with indigenous roots. He joined Simón Bolívar's army in 1819 and showed great skill in battles like Ayacucho. After the country of Gran Colombia broke apart, he was sent away to Venezuela.

He later traveled to Europe, where he learned about new ideas like utopian socialism. When he returned to Colombia in 1840, he joined groups called the Democratic Societies. These groups were made up of middle-class workers and pushed for reforms.

Melo supported President José Hilario López, the first Liberal president. But as the Liberal Party split, Melo took power in a sudden move called a coup d'etat in 1854. He ruled for eight months before an alliance of Conservatives and other Liberals overthrew him.

He was again sent away, this time to Central America. There, he fought against an American mercenary named William Walker who tried to take over Nicaragua. He then supported Mexican President Benito Juárez in a war in Mexico. In 1860, conservative troops captured and executed him in Chiapas, Mexico.

Today, José María Melo is seen as a controversial figure in Colombian history. Some historians now view him as a very progressive leader whose ideas for change were stopped by powerful groups. Many on the Colombian left, including President Gustavo Petro, see him as a hero who died for his beliefs.

Contents

Early Life and Indigenous Roots

José María Dionisio Melo y Ortiz was born on October 9, 1800. His parents were Manuel Antonio Melo and María Antonia Ortiz. He was born in Chaparral, Tolima, a small town in what was then the Viceroyalty of New Granada. He grew up in Ibagué, the main city of the province.

Melo had Pijao ancestry, which means he had indigenous roots. Because of this, he is considered the only Colombian president with a clear claim to indigenous heritage. Some historians have debated how much indigenous ancestry he had. They note that his parents were listed as "white nobles" from important colonial families. However, others point out that Melo was not seen as part of the criollo elite, unlike leaders like Simón Bolívar or Francisco de Paula Santander.

Fighting for Independence

Melo joined the army fighting for independence on April 21, 1819. He became a lieutenant in the army led by Simón Bolívar. This army had just entered New Granada (now Colombia) from Venezuela.

Melo quickly showed his skills as a military leader. He fought in many important battles. These included battles at Popayán, Pitayó, and Jenoy. He also fought in the battles of Bomboná and Pichincha in 1822, which helped Ecuador gain its freedom. Later, he fought in Junín, Mataró, and Ayacucho in 1824. These battles secured Peru's independence from Spain.

Melo was also part of the army that surrounded the fortress city of Callao in 1825. This led to the fall of the last Spanish stronghold in South America.

After Independence: Gran Colombia

After the Spanish were defeated, Melo stayed with Bolívar's army. He fought in the war between Gran Colombia (a large country that included modern-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama) and Peru. Melo fought in the Battle of Portete de Tarqui in 1829. This battle ended in a tie between the two forces.

Even though the war with Peru ended, Gran Colombia faced many problems. Venezuela and Ecuador left the union. Bolívar resigned as president in 1830. Domingo Caycedo became president of the new Republic of New Granada. In September 1830, General Rafael Urdaneta overthrew Caycedo. Urdaneta wanted Bolívar to return. But this attempt failed, and Caycedo came back to power. Urdaneta and his supporters, including Melo, were arrested. They were later sent away to Dutch Curaçao in August 1831.

First Time in Exile

Melo went to Venezuela and settled in Caracas. There, he married María Teresa Vargas y París. In Caracas, Melo met military officers who wanted Gran Colombia to be reunited. They were against the government of José María Vargas, which was conservative and favored separation. They also opposed José Antonio Páez, a powerful leader who supported Venezuela's separation.

In 1835, Melo and this group, led by Santiago Mariño, started a rebellion. It was called the Revolution of the Reforms. They wanted Gran Colombia to be restored and asked for political and social changes. They managed to remove Vargas from power. But Páez gathered an army and forced the rebels to leave Caracas. The rebels who survived went into exile, some to the Dutch Antilles and others to Nicaragua.

Melo traveled to Europe in December 1836. He studied at the Military Academy in Bremen, Germany. He became very interested in socialist ideas that were being discussed there. Melo was especially drawn to early utopian thinkers like Charles Fourier and Henri de Saint-Simon. He also liked the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Louis Auguste Blanqui. Melo was also interested in the Chartist movement in England and the work of French socialist Flora Tristan.

Coming Back to Colombia

The Democratic Societies

Melo returned to Colombia in 1841. This was possible because President José Ignacio de Márquez offered a pardon during the War of the Supremes. Even though he had military training from Germany, he did not rejoin the army. Instead, he settled in Ibagué. He started several businesses and even taught at the Colegio de San Simón. He eventually became an important political leader in his region.

After returning, Melo helped start the "Democratic Societies." These were political groups that brought together artisan workers and liberal thinkers. The groups used ideas from Saint-Simon, Fourier, and French socialist Louis Blanc. They also held readings of the Bible in Spanish, giving them radical interpretations.

The artisans in these groups wanted the government to put tariffs (taxes) on goods imported from industrial countries like England and the United States. They believed these imports hurt the growth of local industries. They also rejected the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty. This treaty, signed by Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera's government, allowed the U.S. to get involved in Panama (which was a Colombian province then) to protect American business interests.

Liberal Government and Party Split

Melo and the Democratic Societies supported the Liberal General José Hilario López in the 1849 presidential elections. López won, and his plans included many of the Democratic Societies' demands. These included ending slavery and separating the church from the government. He also worked on land reform and giving more power to local governments.

In June 1849, President López appointed Melo as the commander of the Hussars Cavalry Corps in Bogotá. In this role, Melo fought against a rebellion in 1851. This rebellion was started by slave owners and conservatives who were against the end of slavery. Melo was promoted to general. He raised a militia of 3,000 volunteers to stop the rebellion in Cundinamarca. Melo defeated the rebels at Guasca. After the rebellion was put down, he became the commander of military forces in Cundinamarca in June 1852.

However, Melo disagreed with López about "resguardos," or indigenous reservations. Melo and the Democratic Societies believed that dissolving these reservations, as López suggested, would allow landowners to use indigenous people as cheap labor.

This disagreement was part of a bigger split within the Liberal Party. One group was the Gólgotas (Golgotha liberals). They believed in free trade. The other group was the Draconianos (Draconian liberals). This group believed that a strong central government and a protectionist economy were needed to protect the republic. After the civil war of 1851, Melo and the Democratic Societies sided more and more with the Draconian group. This was mainly because the artisans strongly opposed free trade.

In August 1850, the artisans demanded protection for their work and a national workshop supported by the government.

Melo started a newspaper called El Orden in 1852. It was meant for military officers and criticized the Golgothas. It also became linked to the Draconian Liberals and the artisans. The newspaper attacked both Conservatives and Golgothas. It accused them of planning to sell Panama to the United States and trying to exile important Draconian leaders like José María Obando.

Obando, a Draconian, was elected president in 1853. He created the Constitution of 1853. This constitution was very advanced for its time in Latin America. It set up a federal system, officially ended slavery, allowed almost all men to vote, and had national elections decided by direct popular vote. Even with these progressive changes, Obando and the Draconians were not fully happy. They knew the Golgothas had written the document.

The Quiroz Incident

In 1853 and 1854, Bogotá became divided between the artisans and the merchant class. This happened especially after a tariff bill failed in the Golgotha-controlled Senate. The city also faced a severe food shortage. Violent street fights broke out between the two groups. A sudden takeover of the government against Obando seemed very possible.

This was the situation during the Quiroz incident in March 1854. Melo's political enemies accused him of being responsible for the death of a soldier under his command, Pedro Ramón Quiroz. Quiroz was hurt in a street fight in January. Melo was accused of hitting him with his sword. In court, Melo showed proof that he was at military headquarters at the time. Quiroz himself, before he died, also said Melo was not responsible. However, the judge and the Mayor of Bogotá were Melo's political opponents. They tried to make this evidence seem unreliable.

As the trial continued in April 1854, the situation in Bogotá worsened. Golgothas fought with Draconians in the streets. Armed artisans gathered, shouting "bread and work, or death." The Vice President, a Golgotha, told President Obando to remove Melo from the army immediately to prevent a rebellion. Obando refused.

Eight Months as President

On April 17, 1854, groups of artisans stormed the homes of important senators in Bogotá and arrested them. The exact start of this revolt is unclear. Some historians believe it was planned by Miguel León, a local blacksmith and leader of a Democratic Society club. Melo arrived with the artisans at the presidential palace. He urged Obando to dissolve Congress and form a temporary government. Obando refused and was arrested.

Melo announced that his government rejected the 1853 constitution and the Golgotha-controlled Congress. He said they tried to harm the Army, which he called an "illustrious body of armed citizens that gave the people independence." He also declared that "liberty shall not perish as long as I exist." Similar artisan revolts happened in Cali and Popayán.

The Golgothas and Conservatives fled to Ibagué and formed a temporary government. They called Melo's government an "audacious military dictatorship." However, Melo's government had strong support from the artisans. One artisan newspaper wrote, "We are free, we are democrats, and we did not abandon our workshops, our homes, and our families, only to give away our sovereignty to one man."

Despite this support, Melo's forces were outnumbered by the "constitutionalists." This group united Golgothas like Tomás de Herrera with Conservatives like Julio Arboleda and Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera. Melo's control was mostly limited to Bogotá. In a major battle south of the capital, Melo's army was defeated. Miguel León, one of the main thinkers of Melo's government, was killed.

After Melo's military defeat, his soldiers and the artisans were treated very harshly. The only military survivors of the Artisans Revolution were 200 people. They were sent on foot to Panama after their property was taken away. Conservatives saw this punishment as a good way to "cleanse Bogotá of the democratic pest."

Final Exile and Death

Melo was put on trial and was expelled from the country for eight years. Some people wanted him to be executed. But this was avoided thanks to some Golgothas, like Manuel Murillo Toro, who argued for mercy and paid his bail. He sailed for Costa Rica on October 23, 1855. We don't know exactly where he went right after his exile. But historians believe he fought in Central America against the American mercenary William Walker. Walker tried to create a slave republic in Nicaragua.

After the victory over Walker, Melo worked as a troop instructor in El Salvador. He briefly moved to Guatemala but then had a disagreement with the country's dictator, Rafael Carrera.

Melo crossed into Mexico on October 10, 1859. At that time, Mexico was in the middle of the War of the Reform. This was another conflict between liberals, led by Benito Juárez, and conservatives. Melo wanted to offer his help directly to Juárez. But he could not reach the Liberal government in Veracruz because of Conservative activity. Instead, he joined the Liberal army through the Governor of Chiapas, Ángel Albino Corzo. Melo became the chief cavalry officer in the Military Department of Comitán. He trained his men, many of whom were Tojolabal Indians, in cavalry warfare.

On June 1, 1860, Melo's cavalry troops were attacked by Conservative forces. This happened at the Juncaná hacienda in La Trinitaria, Chiapas. After several hours of fighting, Melo's defense collapsed. Melo was wounded and captured by the rebel forces. The Conservative general ordered Melo to be killed. The Colombian general was executed by a firing squad.

Melo's position in the Liberal army was taken by José Pantaleón Domínguez. He managed to stop the Conservative uprising in Chiapas. Melo was survived by his son, Máximo Melo Granados. His son married the daughter of the governor of Chiapas, Ángel Albino Corzo, and stayed in Mexico.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: José María Melo para niños

In Spanish: José María Melo para niños