Julia Stephen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Julia Stephen

|

|

|---|---|

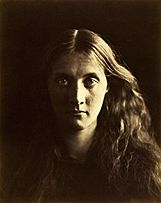

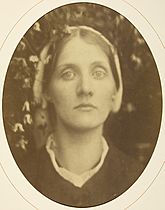

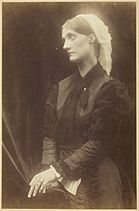

Julia Stephen in 1872, photographed by her aunt Julia Margaret Cameron

|

|

| Born | 7 February 1846 |

| Died | 5 May 1895 (aged 49) |

Julia Prinsep Stephen (born Jackson, and later Duckworth; 7 February 1846 – 5 May 1895) was an English Pre-Raphaelite model and a kind helper of others. She was the wife of the writer Leslie Stephen. She was also the mother of famous artists and writers, including Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. They were part of the Bloomsbury Group, a group of thinkers and artists.

Julia Prinsep Jackson was born in Calcutta, India. When she was two, her mother and two sisters moved back to England. She became the favorite model of her aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron, a famous photographer. Her aunt took more than 50 pictures of her. Julia often visited Little Holland House, a place where many artists and writers met. There, she became known to several Pre-Raphaelite painters who included her in their artworks.

In 1867, Julia married Herbert Duckworth, a lawyer. Sadly, she became a widow soon after, with three young children. She was very sad but decided to help others by nursing and doing charity work. She also became interested in the writings of Leslie Stephen. They shared a friend, Anny Thackeray, who was Leslie's sister-in-law.

After Leslie Stephen's wife died in 1875, he and Julia became close friends. They married in 1878. Julia and Leslie Stephen had four more children. They lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate in South Kensington, London. Leslie's seven-year-old daughter, Laura, who had a mental disability, also lived with them. Many of Julia's seven children and their families became well-known. Besides her family duties and modeling, she wrote a book called Notes from Sick Rooms in 1883. This book was based on her nursing experiences.

She also wrote stories for her children. These stories were published after her death as Stories for Children. Julia Stephen believed that women's work was just as important as men's. However, she thought they should work in different areas. She did not support the movement for women to get the right to vote. The Stephens often had many visitors at their London home. They also spent summers at their house in St Ives, Cornwall. All her duties at home and outside eventually made her very tired. Julia Stephen died at home in 1895, at age 49, after getting rheumatic fever. Her youngest child was only 11 years old. Her daughter, Virginia Woolf, wrote a lot about their family life in her books and personal writings.

Julia's Life Story

Her Family Background

Julia Stephen was born Julia Prinsep Jackson in Calcutta, India, on 7 February 1846. Her parents were Maria "Mia" Theodosia Pattle and John Jackson. Both came from Anglo-Indian families. Her mother's mother, Adeline Marie Pattle, was French. Her father was a doctor who worked for the East India Company. He was also a professor at Calcutta Medical College. While her father came from humble beginnings, he became very successful. The Pattle family, on her mother's side, was well-known in Anglo-Bengali society.

Maria Pattle was one of eight sisters famous for their beauty and lively personalities. They spoke Hindustani among themselves. They were quite a sensation when they visited London and Paris. Julia's parents married in Calcutta in 1837. They had six children. Julia was the youngest of three daughters who survived. The Jackson family was well-educated and loved literature and art.

Her Early Years (1846–1867)

In 1846, Julia's two older sisters were sent to England for health reasons. They stayed with their mother's sister, Sarah Monckton Pattle, at Little Holland House in Kensington. Julia and her mother joined them in 1848 when Julia was two. Later, the family moved to Well Walk, Hampstead. Her father came from India in 1855. The family lived in Hendon at Brent Lodge. Julia was home schooled there.

Julia's sisters, Mary and Adeline, married soon after. Adeline married Henry Vaughan in 1856. Mary married Herbert Fisher in 1862. This left Julia as her mother's companion and caregiver. Her mother had poor health from about 1856. Julia often traveled with her to find cures. On one trip to Venice in 1862, she met Herbert Duckworth. He was a friend of her new brother-in-law, Herbert Fisher. Julia would later marry Herbert Duckworth. In 1866, the Jacksons moved to Saxonbury, near Tunbridge Wells. There, she met Leslie Stephen, who would become her second husband. He described Saxonbury as a "good country house with a pleasant garden."

The Pattle sisters and their families were important connections for Julia. Her aunt, Sarah Monckton Pattle, ran a famous gathering place at Little Holland House. It was called the "Enchanted Palace." Many important people visited there, like Disraeli, Carlyle, and Tennyson. The painter George Frederic Watts lived and worked there. Edward Burne-Jones also stayed there for a while. Julia spent much of her childhood at Little Holland House.

It was at Little Holland House that Julia became known to Pre-Raphaelite painters. These included Burne-Jones, William Holman Hunt, and Frederick Leighton. She modeled for all of them (see Gallery I). She also met writers like William Thackeray and George Meredith. She became friends with Thackeray's daughters, Anne and Minny. Julia was much admired for her beauty. Leonard Woolf called her "one of the most beautiful women in England." In 1864, at age 18, she turned down marriage proposals from Hunt and the sculptor, Thomas Woolner. Leslie Stephen later said that Hunt only married his second wife because she looked like Julia. Julia was also a model for the sculptor Carlo Marochetti. He made a bust of her, which is now at the Charleston Farmhouse. Julia always had many admirers. She was tall for her time and had practical hands. She did not care much for vanity or fashion.

Her Marriages

First Marriage: Herbert Duckworth (1867–1870)

On 1 February 1867, at age 21, Julia got engaged to Herbert Duckworth. He was a Cambridge University graduate and a lawyer. They married on 4 May. Julia Margaret Cameron took many photos of her during this time. Cameron saw these photos as symbols of change. Their marriage was happy. Julia later said she had "the greatest happiness that can fall to the lot of a woman." Leslie Stephen, Julia's second husband, knew Herbert Duckworth from their time at Cambridge. He described Herbert as "simple, straight forward and manly."

The Duckworths lived at 38 Bryanston Square in London. Their first child was born on 5 March 1868. Two more children followed quickly. Their third child, Gerald Duckworth, was born six weeks after his father's sudden death in September 1870. Herbert died at age 37 from an internal infection. He was said to be reaching for a fig for Julia when it happened. He died within 24 hours.

Julia and Herbert Duckworth had three children:

- George (born 1868), who became a civil servant.

- Stella (born 1869), who died at age 28.

- Gerald (born 1870), who started Duckworth Publishing.

A Time of Sadness (1870–1878)

Julia was married for only three years. Her husband's death left her heartbroken. She felt that "life seemed a shipwreck." But she kept going for her children. She later told Leslie Stephen, "I was only 24 when it all seemed a shipwreck, and I knew that I had to live on." Her sadness made her strong and aware of others' pain. She decided to reject religion and the idea of happiness for herself. Leslie Stephen noticed that "she had accepted sorrow as her lifelong partner."

During this time, she started nursing the sick and dying to feel useful. She also read the writings of Leslie Stephen, who was an agnostic (someone who believes it's impossible to know if God exists). Leslie Stephen said, "She became a kind of sister of mercy." Whenever there was trouble or illness in her family, Julia was called to help. After her husband died, she moved in with her parents on the Freshwater, Isle of Wight. She also spent a lot of time at her aunt Julia Margaret Cameron's home in Freshwater. Her aunt took many photographs of her during this period (see Gallery II). Julia also resisted her aunt's attempts to get her to remarry.

Second Marriage: Leslie Stephen (1878–1895)

Julia became friends with Leslie Stephen through his writings and a mutual friend, Anne Thackeray. Leslie Stephen had married Anne's younger sister, Minny Thackeray, in 1867. Minny died in childbirth in 1875, leaving him with a daughter, Laura, who had a disability. After Minny's death, Leslie lived with Anne. Julia helped them move next door to her at 13 (later 22) Hyde Park Gate in South Kensington in 1876. This was a very respectable part of London. It was hoped that Julia's children would be companions for Laura, who was becoming harder to manage. In 1877, Leslie made Julia one of Laura's guardians.

Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth became close friends. She saw him as someone who needed care. They shared their feelings about sadness and duty. Leslie Stephen was a well-known writer and came from a respected family. In January 1877, Leslie Stephen realized he loved Julia. He proposed to her on 5 February. Julia at first said no. She thought about dedicating her life to helping others, like living in a convent. But when Anne Thackeray married in August 1877, Julia changed her mind. She realized she didn't want to be separated from Leslie.

On 5 January 1878, Julia Duckworth and Leslie Stephen got engaged. They married on 26 March at Kensington Church. Julia was 32 and Leslie was 46. Leslie and his daughter Laura moved into Julia's house at 22 Hyde Park Gate. Julia lived there for the rest of her life. She continued her modeling career. Burne-Jones's Annunciation was finished in 1879. Their first child, Vanessa, was born shortly after on 30 May. Julia had decided to have no more children after Vanessa. However, three more children were born over the next four years.

Their marriage was happy. Leslie Stephen called it a "deep strong current of calm inward happiness." He wrote that their children were "a pure delight" to Julia. The Stephens were considered part of the "intellectual aristocracy." They were financially comfortable. They were seen as ideal Victorian parents: a leading writer and a woman admired for her beauty, wit, and kindness. Leslie treated her like a goddess, and she took care of him. However, Julia told him she would never give up her nursing work.

In the early 1880s, Leslie Stephen read a book about Thomas Carlyle. He was shocked by how Carlyle had treated his wife. He wondered if his own marriage had similar problems. Leslie, who loved mountaineering, had a mental breakdown in 1888 from overwork. They visited the Swiss Alps for three weeks. Laura Stephen became more difficult to manage. She had violent outbursts. She was eventually sent away to a governess in 1886 and later to a hospital in 1893. The family had little contact with her after that. In 1891, Vanessa and Virginia Stephen started the Hyde Park Gate News, a family newspaper.

Their Home at 22 Hyde Park Gate

Number 22 Hyde Park Gate was a narrow street in South Kensington, London. It was near the Royal Albert Hall and Hyde Park. The family often walked in Hyde Park. The house was built in the early 1800s for upper-middle-class families. It soon became too small for their growing family. In 1886, they added a new top floor and a bathroom. It was a tall but narrow house with no running water at first. Servants worked in the basement. The ground floor had a drawing room and a library. Julia and Leslie's bedrooms were on the first floor. The Duckworth children's rooms were on the next floor. The Stephen children's nurseries were on two higher floors. The servants' bedrooms were in the attic. The house was dimly lit and full of furniture and paintings.

The younger Stephen children formed a close group inside the house. Life in London was very different from their summers in Cornwall. Their outdoor activities were mainly walks in Hyde Park. Their daily life revolved around their lessons.

Summers at Talland House (1882–1894)

Leslie Stephen enjoyed hiking in Cornwall. In 1881, he found a house in St Ives and leased it. The best part of the house was its view of Porthminster Bay and the Godrevy Lighthouse. The young Virginia Woolf could see the lighthouse from her window. It later became a central part of her novel To the Lighthouse. Talland House was a large, square house with a terraced garden that sloped towards the sea.

Every year from 1882 to 1894, the Stephens leased Talland House for their summer home. Leslie Stephen called it "a pocket-paradise." He said it was a place of "intense domestic happiness." For the children, it was the best part of their year. Virginia Woolf later wrote about a summer day in August 1890. She remembered the sounds of children playing and the sea. She felt her life was "built on that." The family did not return to Talland House after Julia's death in May 1895.

In both London and Cornwall, Julia was always hosting guests. She loved to play matchmaker, believing everyone should be married. While Cornwall was supposed to be a break, Julia quickly started caring for the sick and poor there, just as she did in London.

At both Hyde Park Gate and Talland House, the family met many famous writers and artists. Guests included Henry James and George Meredith. The children heard many intellectual conversations.

Julia and Leslie Stephen had four children:

- Vanessa (born 1879), who married Clive Bell.

- Thoby (born 1880), who helped start the Bloomsbury Group.

- Virginia (born 1882), who married Leonard Woolf.

- Adrian (born 1883), who married Karin Costelloe.

4. Photograph by Vanessa Bell, in the library; 5. Julia died in May 1895. This would be the family's last summer in St Ives

Her Relationships with Family

Much of what we know about Julia Stephen comes from her husband, Leslie Stephen, and her daughter, Virginia Woolf. Virginia was only 13 when her mother died. Woolf often wrote about her mother in her diaries and essays. She described her mother as "astonishingly beautiful." Her novel To The Lighthouse features a character based on Julia Stephen. Vanessa, who was 15 when her mother died, also shared her memories through her daughter, Angelica Garnett.

As the youngest daughter, Julia was her mother's favorite. This was partly because she constantly cared for her mother, who was often ill. Julia's mother died in 1892. Leslie Stephen wrote about Julia with great respect in his Mausoleum Book. He saw her as a "beloved angel" and a saint. He described her beauty as matching her kind and noble soul. She lived a life dedicated to her family and helping others. Virginia Woolf noted that her mother's charity work was different from others. She had great sympathy, judgment, and a sense of humor.

Julia shared the education of her children with her husband. The girls were mostly schooled at home. The boys went to private schools and then university, as was common then. Julia taught them Latin, French, and History. Leslie taught them mathematics. They also had piano lessons.

Julia managed her husband's sad moods and his need for attention. This sometimes made her children resentful. She also nursed her parents and her sister Adeline during their final illnesses. Leslie Stephen also had periods of poor health. He suffered a breakdown from overwork in 1888–1889. Julia's frequent absences and duties made her young children feel insecure. They became very dependent on Stella Duckworth, Julia's eldest daughter, who was also very selfless.

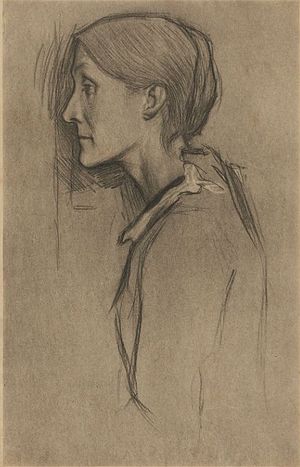

Julia greatly admired her husband's intelligence. She believed her own work, though different, was just as important as his. Virginia Woolf noted that her mother's "nervous energy dominated the family." While Virginia felt closest to her father, Vanessa said her mother was her favorite parent. Julia's grandson, Quentin Bell, described her as saintly and kind. He said she was always there to help. However, the constant demands on her eventually wore her down. She suffered from depression. William Rothenstein's drawings of her in the 1890s show her looking "haunted, worn down and beautiful."

Running a large household with many servants was a big job. Julia believed a woman's main role was to serve her husband. She managed the family finances and supervised the servants. Sophie Farrell, a cook, worked for the family for many years. Virginia Woolf remembered her mother "adding up the weekly books."

Her Death

On 5 May 1895, Julia died at her home. She was 49 years old. She died from heart failure caused by influenza. She left her husband with four young children, aged 11 to 15. Her children from her first marriage were adults. Stella, then 26, took over her mother's duties until she married two years later. Julia was buried on 8 May at Highgate Cemetery. Her husband, daughter Stella, and son Thoby were later buried there too.

Her Work

As an Artist's Model

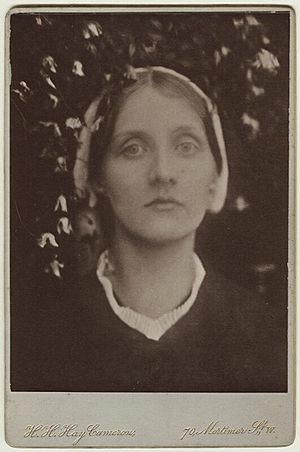

Julia Stephen is most famous for being a model. She posed for Pre-Raphaelite painters and her aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron. She was Cameron's favorite model. Cameron took over 50 portraits of Julia (see Gallery II). These photos show Julia's moods and thoughts. Cameron was fascinated by Julia. Julia's image from Cameron's early photos shows her as a delicate figure with large, soulful eyes and long, wild hair.

Most of Cameron's photos of Julia were taken between 1864 and 1875. Some were taken during her engagement in 1867. Cameron called one of these photos "the real nobility I prize above all things." In this photo, Cameron used strong side lighting to highlight Julia's neck and head. This showed her strength as she was about to marry. Cameron often used a soft focus effect, like in Julia Duckworth 1867. One photo was titled My Favorite Picture of all my works. In this one, Julia's eyes are looking down. Another, My niece Julia full face, shows her staring directly at the camera. This suggests she was a strong, independent woman. These photos are very different from the ones taken during her widowhood (1870–1878). Those photos show her looking thin and pale, reflecting her grief.

Helping Others and Charity Work

Julia worked tirelessly to run her household and care for her relatives. She also helped friends and people in need. She had a strong sense of social justice. She traveled around London by bus, nursing the sick in hospitals and workhouses (places where poor people lived and worked). She later wrote about her nursing experiences in her book Notes from Sick Rooms (1883). This book gives practical advice on good nursing. For example, she describes how uncomfortable bread crumbs in the bed can be for a sick person.

She also spoke up for the sick and poor. She wrote a letter protesting against cutting off beer rations for poor women in a workhouse in Fulham. She argued that agnosticism (not believing in God) was not against being spiritual or charitable. She used her experience of caring for the sick and dying to support her arguments.

At home, Virginia Woolf described how Julia used one part of the drawing room to give advice and comfort. She was like an "angel in the house."

Her Views

Julia had strong opinions about women's roles in society. She was not a feminist and even signed a petition against women getting the right to vote in 1889. She believed that women had their own important roles and role models. She pointed her daughters to Florence Nightingale and Octavia Hill as examples. Julia believed that men and women had different roles in life, but that both were equally valuable. Her views were common for an upper-middle-class Victorian woman. Interestingly, in her family, the traditional roles were somewhat reversed. Leslie Stephen worked from home, while she often worked outside the home.

Despite her views, she was friends with strong supporters of women's rights, like the actress Elizabeth Robins. Robins remembered that Julia's calm face was misleading. She said Julia could say surprising things that seemed "vicious" from such a "Madonna face." Julia Stephen was mostly a traditional Victorian lady. She supported the system of live-in servants and believed in a "strong bond" between the lady of the house and her staff.

Her Writings

Julia Stephen wrote a book, a collection of children's stories, and several essays that were not published during her lifetime. Her book, Notes from Sick Rooms, was published in 1883. It was a guide to nursing. It was later republished with Virginia Woolf's On Being Ill. She also wrote Stories for Children between 1880 and 1884. These stories taught about family values and being kind to animals. Some stories, like Cat's Meat, showed the challenges in Julia's own life. Her writings show her as decisive, traditional, and practical, with a sharp wit.

She also wrote the biography for Julia Margaret Cameron in the Dictionary of National Biography. Her husband was the first editor of this dictionary. This was one of the few biographies of women in the book. Virginia Woolf later wished there were more stories about ordinary women in it. Among her essays, Agnostic women defended her charity work as an agnostic. She also wrote two essays about managing households and servants.

Her Legacy

Julia Stephen is seen as the mother of the Bloomsbury Group. She was a beautiful muse (inspiration) for the Pre-Raphaelites. We know what she looked like from many paintings and photographs. George Watts's portrait of Julia (1875) hung in Leslie Stephen's study. Later, it was at Vanessa Bell's Charleston Farmhouse, where it still is. The family owned many of Julia Margaret Cameron's photos of Julia. After Leslie Stephen died in 1904, the children moved to 46 Gordon Square. They hung five of these photos in their entrance hall. These images were an important link to their mother, who died too soon.

Julia's importance is not just in herself, but in how she influenced others. Many of her children and their descendants became famous. She played a role in English thought and literature in the late 1800s. Julia Stephen fit the Victorian ideal of a perfect woman: good, beautiful, capable, and helpful. She passed on her ideas about life to her children. Some even say that Virginia Woolf's writing style was similar to her mother's in Notes for Sickrooms. Even though Julia's daughters rejected some Victorian traditions, her influence can be seen. Virginia Woolf wore her mother's chignon hairstyle and even her dress in Vogue magazine. Vanessa Bell also wore her mother's dresses. Virginia Woolf also wrote with her mother's pen.

Julia Stephen wrote many letters throughout her life. Leslie Stephen said they "never passed a day apart without exchanging letters." After her death, the Julia Prinsep Stephen Nursing Association Fund was created to honor her. Leslie Stephen said she made "many friends among the poor" with her kind ways.

Her Influence on Virginia Woolf

Many people have studied how Julia Stephen influenced her daughter, Virginia Woolf. Woolf said her first memory, and most important, was of her mother. Her memories of her mother were like an obsession. Woolf had her first major mental breakdown when her mother died in 1895. This loss affected her deeply throughout her life.

Woolf wrote that her mother was "beautiful, emphatic... closer than any of the living are." She felt her mother was an "invisible presence" in her life. Some scholars argue that the mother-daughter relationship is a constant theme in Woolf's writing. Woolf saw her mother as a "saint" who was perfect but also intimidating. Her mother's frequent absences and early death made Woolf feel a sense of loss. Julia's influence and memory were always present in Woolf's life and work. Woolf wrote, "she has haunted me."

Images for kids

-

Virginia Woolf in 1902, with chignon, by Beresford