Julio de Urquijo e Ibarra facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Julio de Urquijo

Count of Urquijo

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Born |

Julio Gabriel de Urquijo e Ibarra

1871 Deusto, Spain

|

| Died | 1950 San Sebastián, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | scientist |

| Known for | linguist |

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista |

Julio de Urquijo e Ibarra (1871-1950) was an important Basque linguist, a person who studies languages. He was also a cultural activist and a Spanish politician who belonged to the Carlist movement. In the Basque language, he called himself Julio Urkixokoa.

Julio de Urquijo served twice as a representative in the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes. This was from 1903 to 1905 and again from 1931 to 1933. He was very active in politics during the late Restoration period in Spain. As a scientist, he helped create many groups that studied the Basque language and culture. These included the Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos (1907) and the Sociedad de Estudios Vascos (1918). He was an expert in Basque paremiology (the study of proverbs) and bibliography (the study of books and their history). He believed that a standard Basque language should develop naturally, rather than being created by an academy.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Julio Gabriel Ospín de Urquijo e Ibarra was born in 1871 into a rich and well-known family. His family came from the Ayala Valley in Spain. Julio's grandfather, Serapio Ospín Urquijo, worked as a secretary for the Bilbao city council for many years. His father, Nicasio Adolfo Ospín Urquijo (1839-1895), was a lawyer and also worked for the city. He even served briefly in the Spanish parliament.

In 1865, Julio's father married María del Rosario de Ibarra (1846-1875). Her family was very wealthy and controlled a large part of the Biscay iron ore mining industry. Rosario's father, Julio's grandfather on his mother's side, was a powerful politician in the region. He led many businesses and held important official positions.

In 1869, Julio's parents moved to Deusto, which was a suburb of Bilbao at the time. They lived in a house called La Cava, which Rosario's father had just finished building. Julio's parents had five children: two daughters and three sons. During the Third Carlist War, the family moved to Santander. Sadly, Julio's mother passed away when he was very young. After that, his aunt, Rafaela Ibarra, helped take care of his early education.

After the war, the family returned to La Cava in 1878, which had been repaired. In 1891, Julio's father and family moved to Bilbao. La Cava remained with his aunt Rafaela.

Julio went to high school at the Instituto de Bilbao. In 1887, he finished high school and started studying law at the Jesuit Deusto college. This college was built with a lot of financial help from the Ibarra family. Julio finished his university studies in 1892, earning a degree in law from the University of Salamanca.

Julio inherited enough money, so he did not need to work as a lawyer. In 1894, he married Vicenta de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate. Her father, Tirso de Olazábal, was a leader of the Carlist movement in Gipuzkoa. Julio and Vicenta lived in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, a town in France, close to the Spanish border. They did not have any children.

Many of Julio's relatives were involved in politics. His older brother, Adolfo, was a politician and a Basque scholar. Julio's younger brother, José, became a conservative politician and a businessman. Julio's aunt Rafaela founded a religious group called the Congregación de los Santos Angeles Custodios. In 1984, she was recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.

Political Life as a Carlist

Some sources say that Julio de Urquijo grew up with Carlist ideas. However, others suggest that his family, especially on his father's side, were more aligned with the Liberal party. Julio's father became more conservative later in life. His older brother joined the Conservative Party.

Julio's political views became clear in the mid-1890s, after he moved to Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Living near his father-in-law, who was a Carlist leader, Julio became involved in the movement.

In 1903, Julio ran for parliament as a Carlist in the Tolosa district and won. For the next two years, he supported Carlist ideas in parliament. He also helped gather support for the party in his local area. In 1905, he ran again but did not win. In 1907, he helped with another Carlist election campaign.

In the early 1900s, Julio de Urquijo, along with Esteban Bilbao and Victor Pradera, were part of a new generation of Carlist activists. The Carlist leader, Carlos VII, and his successor, Jaime III, supported these younger members. Julio was friends with Don Jaime and traveled with him sometimes. From 1907 to 1909, Urquijo served as the political secretary for Carlos VII.

After some unrest in Catalonia in 1909, Urquijo helped his father-in-law with activities to support the Carlist cause. When his father-in-law was told to move by French authorities, Julio briefly took over supervising these efforts until things calmed down.

Later Political Years

In the 1910s, Julio de Urquijo focused more on Basque cultural projects. He was less involved in Carlist politics during this time. However, he did confront some rebellious Carlist members in 1919. He was not very active in Carlist politics during the final years of the Spanish monarchy or during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera. His political views were mainly mentioned when people talked about his work with the Sociedad de Estudios Vascos. For example, in 1929, he was described as an unusual Carlist when he joined the Real Academia Española.

In the 1931 elections, the Carlists were trying to form an alliance with the PNV (Basque Nationalist Party). Urquijo was a well-known figure in the Basque cultural movement, making him a good candidate. He won a seat in parliament for Gipuzkoa. He joined the Basque-Carlist group and strongly defended the Catholic Church.

The idea of an autonomy status for the Basque-Navarre region caused disagreements between nationalists and Carlists. Urquijo was not a main leader for or against this idea. He attended a key meeting about it but left early. Soon after, the Catholic-Carlist group in parliament broke apart.

In the 1933 election, the alliance between Carlists and Basques was no longer possible. Urquijo did not run as a candidate. There is not much information about his political activities in the last years of the Republic. When the Spanish Civil War started in 1936, he was in San Sebastián. He was not arrested, but he feared for his life and fled. He returned to Gipuzkoa after the province was captured by the Nationalists. However, he did not participate in politics after that.

Contributions as a Linguist

Julio de Urquijo's teachers at Deusto, Román Biel and Tomás Escriche Mieg, sparked his interest in linguistics. This interest grew stronger through the work of Julio Cejador and Resurreción María Azkue. Azkue was the family's chaplain and became a professor of Basque language in 1888.

Initially, Julio was interested in comparative linguistics, which looks at how languages are related. He also studied artificial languages. In 1889, he published his first work, a small book in volapük, an artificial language. He even joined the St. Petersburg volapük Academy. However, he became disappointed with volapük and stopped studying it in 1905.

Urquijo's disappointment with artificial languages led him to study Basque. Around 1905, he started writing to foreign Basque scholars like Julien Vinson and Hugo Schuchardt. He met Schuchardt twice. Urquijo's interest in Basque focused on its history and how it was influenced by other languages. He gradually became a skilled partner to both Schuchardt and Azkue.

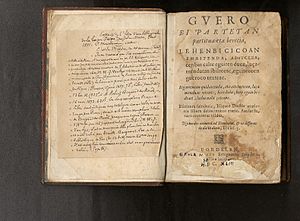

Julio de Urquijo knew that he lacked formal training in linguistics. This made him very critical of his own work. He focused on making sure his research was accurate, well-documented, and systematic. He also collected old Basque books and prints. During election campaigns, he would ask his agents to look for books instead of just votes! He built a huge library of about 11,000 items, including many rare books. In 1936, this collection was saved from the Civil War. His love for books led him to become an expert in bibliography.

Organizing Basque Studies

Urquijo believed that Basque studies needed to be organized to last. In 1901, he helped create Eskualzaleen Biltzarra, a group that promoted Basque culture. He also had the idea for a "Basque Language Academy."

In 1907, Urquijo used his own money to start the Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos (RIEV). He was the owner and manager, and he attracted many Spanish and foreign experts to write for it. The magazine focused on Basque language and literature. It played a key role in bringing scientific standards to Basque studies, publishing old Basque texts, and expanding research. By 1936, 27 volumes were published, making RIEV the most important platform for Basque scientific exchange.

In 1908, Urquijo became president of Eskualzaleen Biltzarra and made the group more active. In 1911, he helped start Euskalerriaren Alde, another magazine promoting Basque culture. He also helped create the Bayonne-based Cercle d'Etudes Euskariennes in 1911 and became its president.

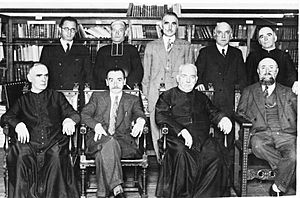

In 1918, Urquijo participated in the First Congress of Basque Studies in Oñati. This led to the creation of the Sociedad de Estudios Vascos (SEV), also known as Eusko Ikaskuntza. Urquijo became its vice-president and a member of its Language and Literature sections. This organization became a very important Basque cultural institution. In 1919, SEV created Euskaltzaindia, the Royal Academy of the Basque language. Urquijo became one of its four main academics. In 1922, he gave ownership of RIEV to SEV but remained its manager.

In 1937, Urquijo became secretary of the re-established RAE. He worked with Azkue to restart Euskaltzaindia. In 1941, the Basque language academy was re-established. In 1943, Urquijo helped found the Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País again, becoming its chairman. This group started its own magazine, Eusko Jakintza, which Urquijo managed.

His Own Research and Writings

Julio de Urquijo's own writings are extensive, with about 300 titles. These include books, articles, and reviews. Most of his important works were written between 1922 and 1929.

His work covered many different areas: general linguistics, comparative linguistics, paremiology (proverbs), onomastics (names), old songs and stories, the origin of the Basque language, folklore, archaeology, heraldry, etymology, music, and literature. He was known for his careful and scientific approach. He avoided wild theories that some other Basque enthusiasts of his time pursued.

Urquijo became an expert in two main areas. The first was bibliography, which fit his systematic nature. He became known as the "greatest Basque bibliographer." The second was paremiology, the study of proverbs, which he found very interesting. Some also say he specialized in Basque dialects and how they changed over time.

Compared to Azkue, Urquijo's own writings were not as extensive, partly because his knowledge of spoken Basque was not as strong. Scholars describe his work as careful and effective, perhaps because he was very self-critical. They also point out that besides his research and organizational work, Urquijo's contribution included many discussions and friendly critiques with other scholars.

Debates and Controversies

As a Basque scholar, Urquijo was involved in several important debates about the Basque language and culture. He agreed with Azkue in opposing the "aranistas" (followers of Sabino Arana). He believed their approach was not scientific and that they created theories that fit their idealized vision of the Basque community. Urquijo wanted a purely scientific approach. He was also against the "aranistas'" focus on linguistic purity and their strange ideas about word origins. He believed that the issue of language should be handled scientifically, not by zealous nationalists. Urquijo also valued the different Basque dialects, while Arana wanted to protect Basque from outside influences.

A big question for the SEV was how to create a unified written Basque. Urquijo was strongly against taking any immediate action. He felt there wasn't enough linguistic evidence to decide, and he liked the diversity of the dialects. He thought that efforts to unify the language were like the strange theories of early Basque scholars. He also opposed creating a committee for new words, believing that new words should come from the people, not from an academy. Urquijo thought it was more important to reprint traditional Basque works, research the language scientifically, and encourage its use. His view won, and SEV and Euskaltzaindia did not take any big steps to unify the language. Some scholars say that the unification, which finally happened in 1968, followed the ideas Urquijo had.

Later scholars have said that SEV focused more on a "traditional Basque Country" than the "real Basque Country." They suggest that Urquijo was largely responsible for this. SEV focused on scientific research, especially historical analysis, and avoided taking a role in regulating or setting language rules. This might have been because Urquijo wanted to avoid conflicts that could damage SEV's neutral image. However, some still criticized Urquijo and SEV for having an ideological bias, arguing that the religious nature of Basque cultural institutions at the time was not truly neutral.

Recognition and Lasting Impact

Julio de Urquijo began to be widely recognized as a scholar in the early 1900s. In 1909, he was made a corresponding member of the Real Academia de la Historia. In 1924, the University of Bonn gave him an honorary doctorate degree. In 1927, he was invited to join the Royal Spanish Academy of Language. By the 1930s, his home and huge library were considered a very special place for Basque tradition. Urquijo himself was called its "high priest."

In 1942, he became a professor at the University of Salamanca, which was his only time teaching. In 1949, the province of Gipuzkoa declared him a "distinguished son," with celebrations and special publications. The same year, he received a high honor, the Grand Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X the Wise. He passed away due to heart disease.

In 1954, a research center called the Seminario de Filología Vasca "Julio de Urquijo" was created in his honor. This center is still active today. In 1971, Euskaltzaindia, the Basque language academy, held celebrations for the 100th anniversary of his birth. His huge library, with 8,000 books and 11,000 other items, became part of the Koldo Mitxelena Kulturunea foundation. There are a few streets named after him in Spain, especially in his hometown of Deusto.

Today, scholars see Urquijo as a very important figure in the revival of Basque culture. He is often listed with other key individuals like Sabino Arana, Miguel de Unamuno, Resurrección Azkue, and Arturo Campión who led this movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. People generally praise Urquijo, even in the active Basque cultural and political world. Even though he was part of the Carlist movement, he is often seen as tolerant, open-minded, and a reformer.

See also

In Spanish: Julio de Urquijo para niños

In Spanish: Julio de Urquijo para niños

- Sociedad de Estudios Vascos

- Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos

- Standard Basque

- Basque language

- Rafaela Ybarra de Vilallonga

- Usera Tunnel scam, where his brother died

- Villa Arbelaiz

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |