Julliberrie's Grave facts for kids

|

|

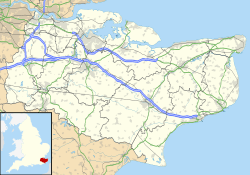

| Coordinates | 51°14′26″N 0°58′30″E / 51.240479°N 0.974888°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Long barrow |

| Designated | 1981 |

| Reference no. | 1013000 |

Julliberrie's Grave, also known as The Giant's Grave, is an ancient burial mound in Kent, England. It's a type of monument called an unchambered long barrow. People built it around 4,000 to 3,800 BCE, during a time called the Early Neolithic period. Today, it is mostly in ruins.

Archaeologists believe that early farming communities built this mound. These communities had just started farming in Britain, learning from people in Europe. Julliberrie's Grave is part of a tradition of building long barrows across Europe. However, it's also special because it belongs to a local group of barrows near the River Stour. Two other known barrows in this group are Shrub's Wood Long Barrow and Jacket's Field Long Barrow.

Julliberrie's Grave is about 44 metres (144 ft) long and 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high. It is 15 metres (49 ft) wide at its widest point. The northern end of the mound has been damaged over time. Unlike many other long barrows, archaeologists haven't found human bones here from the Early Neolithic period. It's possible that no one was buried there, or that the burials were in the lost northern part.

Archaeologists found a broken stone axe in the middle of the mound. They think it was placed there on purpose, as part of a special ritual. A rectangular pit was also dug on the western side of the barrow. This pit likely held a ritual offering of plants or other natural materials.

Later, during the Iron Age, people used the ditch around the barrow for a fire. In the Romano-British period, people buried human remains and a collection of coins near the mound. Over many centuries, local folklore stories grew about the site. People believed it was the grave of a giant or a whole army with their horses.

People interested in old things, called antiquarians, started studying the site in the 1600s. However, chalk quarrying heavily damaged it in the 1700s. Antiquarians dug into the barrow a few times in the 1700s and 1800s. More careful archaeological digs happened in the 1930s. Today, Julliberrie's Grave is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, which means it's protected. Visitors can explore it all year round.

Contents

Where is Julliberrie's Grave?

Julliberrie's Grave sits on a hillside overlooking the eastern side of the River Stour. It is about half a mile southeast of St Mary's Church, Chilham. You can see it from a public path nearby. It is protected by British law as a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Why are Long Barrows Important?

The Early Neolithic period was a time of big changes in Britain. Between 4500 and 3800 BCE, people started farming instead of hunting and gathering. This change happened because of contact with people from Europe. Kent was an important area for these new ideas and people to arrive. This was because of its location near the River Thames and close to Europe.

Most of Britain was covered in forests during this time. People likely herded cattle and moved around a lot. They didn't build many permanent homes. Even though people across Britain shared similar tools and ideas, there were differences in how they lived and built things.

Ancient Tombs and Beliefs

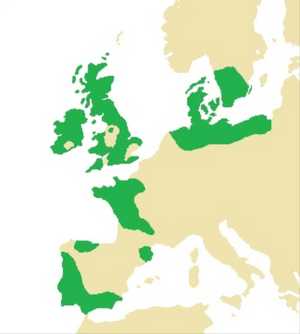

In Western Europe, the Early Neolithic was the first time humans built huge structures in the landscape. Many of these were tombs for the dead. People rarely buried individuals alone. Instead, they buried groups of people from their community together. These large tombs, made of wood or stone, started in Europe and then came to Britain.

Early Neolithic people in Britain cared a lot about how they buried their dead. Many archaeologists think this is because they believed in an "ancestor cult." This means they honored the spirits of their ancestors. They thought these spirits could help the living. Because other ceremonies might have happened at these sites, some historians call them "tomb-shrines."

These ancient tombs were often built on hills or slopes. They might have marked the boundaries between different groups of people. Some archaeologists think they showed who owned the land. Others suggest they were markers along paths used for herding animals. Building these monuments might have shown a new way of thinking about owning land. Some also believe these sites were already considered sacred by earlier hunter-gatherers.

Archaeologists have found different styles of these tombs in Britain. In northern Britain and Ireland, there were "passage graves." These had narrow stone passages leading to burial chambers. In central Britain, long mounds with chambers were common. In eastern and southeastern Britain, like Kent, "earthen long barrows" were more typical. These were often made of wood because large stones were rare.

About twelve Neolithic long barrows are known in Kent. The most famous are the Medway Megaliths. These are near the River Medway and have stone burial chambers. Julliberrie's Grave and the other Stour long barrows are different because they don't use large stones. This was likely a choice, as stones were available nearby. Archaeologists see the Stour long barrows as a unique group.

What Does Julliberrie's Grave Look Like?

Julliberrie's Grave is shaped like a trapezoid. It points from north-northwest to south-southeast. In the 1930s, it was about 43.9 metres (144 ft) long. It was 14.6 metres (48 ft) wide at its northern end and 12.8 metres (42 ft) wide at its southern end. The highest part of the mound was 2.1 metres (6 ft 11 in) tall. An old letter from 1703 said it was once even bigger, over 54.8 metres (180 ft) long.

A ditch goes around the southern end and sides of the mound. We don't know if the ditch went all the way around the northern end because that part is damaged. Some other long barrows in southern Britain also have ditches that completely encircle them.

No main burials of human remains have been found inside Julliberrie's Grave. This means it might be one of the long barrows that didn't contain burials. Or, the burials could have been in the northern part that was destroyed. It's also possible that the mound was not for burials at all, but instead marked a territory.

Archaeologists haven't been able to give Julliberrie's Grave an exact date. But based on its shape and the lack of burials, it seems to be a later type of long barrow. An archaeologist named Stuart Piggott thought it was built late in the Early Neolithic period, based on a polished axe-head found there.

Special Items Found Inside

During an excavation in 1937, a broken polished stone axe was found deep inside the southern end of the mound. This type of axe was very valuable back then. Because of where it was found, archaeologists think it was placed there on purpose as part of a ritual.

Finding an axe inside a monument isn't unique to Julliberrie's Grave. Axes have been found in other Early Neolithic sites in Britain. The style of the axe found here is similar to axes found in the Netherlands, Germany, and Scandinavia. This suggests a connection between Kent and those regions long ago.

On the western side of the mound, a rectangular pit was dug. It was about 4.7 metres (15 ft) long and 2.3 metres (7 ft 7 in) wide, and at least 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) deep. It looked like it was dug and filled very carefully. At the bottom, there was some chalk and organic material that archaeologists couldn't identify. They think it was an item placed there as an offering. This pit was likely dug shortly after the mound was built. Archaeologists believe it held a "ritual offering made at the completion of the barrow."

Later History: Iron Age and Roman Times

Archaeologists found signs that people used the site during the British Iron Age. A hearth (a fireplace) was found in the western ditch of the barrow. Two broken pots were found near it.

During the Romano-British period, people showed a lot of interest in Julliberrie's Grave. Archaeologists found several Roman burials near the southern part of the mound. These included both inhumations (whole bodies) and cremations (burnt remains).

One burial was a child, aged 5 to 7. It was buried with a bronze brooch, a bronze bracelet, a pottery dish, and a cup. These items were from the mid-first century CE. Another burial was a young woman, about 17 years old, also buried with a dish and a cup from the same time. There was also evidence of an infant burial. A third Roman burial contained six pottery vessels, including a bowl with the cremated remains of a young adult.

A pot filled with Roman coins from the time of Emperor Constantine was found near the barrow in the 1800s. During the 1930s digs, eight more Roman coins were found. A Roman hearth was also found on the southeastern side of the mound. It was used to dump animal bones, oyster shells, glass, and pottery. Archaeologists think this was a "rubbish dump," possibly from a memorial near the burials.

It was common for Romano-British people to bury their dead around older prehistoric mounds. Archaeologists think this might be because they saw these ancient sites as connected to local gods, ancestors, or their group's identity. These sites might have been important for people to show who they were and their place in society, separate from Roman rule.

Damage Over Time

Over the centuries, Julliberrie's Grave has been damaged. An old chalk quarry likely destroyed its northern end. By the 1930s, this quarry was no longer active and was covered by plants. Some damage also came from rainwater dripping from trees and from farming (ploughing) on the western side.

Names and Old Stories

By the early 1900s, locals called the site "Julliberrie's," "The Grave," and "The Giant's Grave." The "berrie" part of the name might come from an old English word for an artificial mound. The "Julli" part could be from a person's name or refer to "jewels" that people thought were hidden inside.

In the 1930s, people still believed the story that a giant was buried there. Another tale said it was the burial place of a hundred horses and a hundred men killed in battle. They couldn't be buried in the local churchyard. A local man also said his father told him not to climb the mound, as it was disrespectful to stand on a grave.

Julliberrie's Grave even appears in a 1936 novel called The Penrose Mystery by R. Austin Freeman.

How We Learned About Julliberrie's Grave

Early Studies and Digs

Unlike other nearby barrows, Julliberrie's Grave has been known for many centuries. The antiquarian William Camden wrote about it in the 1600s. He thought it was the burial place of Julius Laberius, a Roman general's officer who died fighting in Britain. Camden's idea was accepted by many later antiquarians.

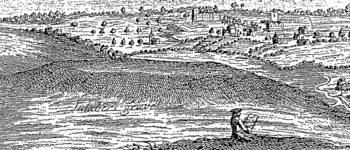

Other famous antiquarians visited the site. John Aubrey visited around 1671. William Stukeley visited in 1722 and 1724, making drawings of the barrow and the surrounding area. These drawings were later turned into engravings for his books.

An excavation of the barrow happened in 1702. Lord Weymouth and Heneage Finch dug a shaft through the middle of the mound. They found a few bones they thought were not human. Finch wrote that it was clearly a "burial-place," but he didn't know "of what people or time." This was one of the earliest organized "barrow openings" in England. Later digs in the 1930s found signs of another, unrecorded excavation.

In the early 1800s, the owner of the site put up a fence around the barrow to stop people from walking on it. This fence was gone by the 1930s. The Roman coin hoard was found when a post hole for this fence was being dug. In 1868, archaeologist John Thurnam was the first to correctly identify it as a long barrow. Later, Flinders Petrie and O. G. S. Crawford also recorded the site.

Jessup's Excavations

In July 1936, archaeologist Ronald Jessup led an excavation of the barrow. The landowner, Sir Edmund Davis, paid for it after the site was featured in a novel. After the dig, Jessup's team helped preserve the barrow by filling rabbit holes and removing thorny bushes.

In 1937, Davis paid for a second excavation, which lasted eight weeks. The main goal was to find good evidence to date the mound. Archaeologists Grahame Clark and Stuart Piggott helped analyze the finds. Jessup's work confirmed that it was a Neolithic long barrow. He also found that the northern end was destroyed and discovered the polished stone axe and the Roman burials.

Another archaeologist, Paul Ashbee, later praised Jessup's excavation. He called it "careful" and "comprehensive." He said it was one of the important long barrow excavations of the 1930s that set a good example for future work after World War II.

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |