Medway Megaliths facts for kids

Three of the Medway Megaliths: Kit's Coty House (left), Little Kit's Coty (above right), and the Coldrum Stones (below right).

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | Early Neolithic |

|---|---|

| Location | Northern Kent |

| Type | Long barrow |

The Medway Megaliths are a special group of ancient stone monuments. They are also sometimes called the Kentish Megaliths. These amazing structures were built a very long time ago, during the Early Neolithic period. This was between 4,000 and 3,000 years before the Common Era (BCE).

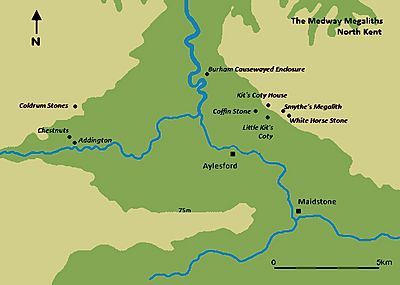

You can find them in the lower valley of the River Medway in Kent, South-East England. They were made from local sarsen stones and earth. These megaliths are the only known prehistoric stone group in eastern England. They are also the most south-easterly group in Britain.

These monuments are unique in Britain. They have special features that make them different from other similar sites. We don't know their exact purpose. However, some were used as tombs for important people. Many experts also believe they were places for religious ceremonies. They show how people in Britain changed from hunter-gatherers to farmers.

Three main tombs are west of the river: the Coldrum Stones, Addington Long Barrow, and Chestnuts Long Barrow. East of the river, there are three more: Kit's Coty House, Little Kit's Coty House, and Smythe's Megalith. Some other large stones, like the Coffin Stone and the White Horse Stone, might be parts of old tombs too. An ancient longhouse and a special fenced area called a causewayed enclosure were also found nearby.

Over time, the Medway Megaliths have been damaged. Some were even purposely destroyed in the late 1200s CE. People started becoming interested in them again in the late 1500s. Back then, they had some wrong ideas about how they were built. Later, archaeologists began to study them scientifically in the late 1800s. Local stories and beliefs have also grown around these sites. Today, some modern Pagans use them as sacred places.

Contents

Life in the Early Neolithic Age

The Early Neolithic period was a time of big changes in Britain. It began around 5,000 BCE. People started to farm instead of hunting and gathering food. This new way of life came from Europe. We don't know if new people arrived or if local people learned farming from others.

By 4500 to 3800 BCE, farming was common across the British Isles. People mostly raised cattle, moving around with their herds. There were different ways of life in different parts of Britain. But everyone shared a similar material culture (the objects they made and used).

There is proof of fighting in Early Neolithic Britain. Some groups built forts to protect themselves. We don't know much about how men and women lived together. But experts think it was probably a male-led society. This is common in societies that raise many animals.

Britain was mostly covered in forests back then. It's not clear how much forest was cleared in Kent during this time. Evidence near the White Horse Stone shows it was still very woody. There were trees like oak, ash, and hazel.

Why did people build tombs?

"The tombs provide the earliest and most tangible evidence of Neolithic people and their customs, and are some of the most impressive and aesthetically distinctive constructions of prehistoric Britain."

The Early Neolithic was the first time humans built huge structures. Many of these were tombs for the dead. They were often made with large stones called "megaliths." People were usually buried together in these tombs. Building these tombs started in Europe. Then, the idea came to Britain around 4,000 BCE.

Neolithic people cared a lot about burying their dead. Experts think they believed in an ancestor cult. This means they honored their ancestors' spirits. They thought these spirits could help them. People might have gone into these tombs, which were also like temples, to perform rituals. They would honor the dead and ask for help. That's why some call them "tomb-shrines."

These tombs were often on hills. They might have marked the edges of different groups' lands. Archaeologist Caroline Malone said they showed "territory, political allegiance, ownership, and ancestors." Some think they were markers for herding paths. Building these huge monuments might have shown that people were claiming the land. Others believe these spots were already sacred to earlier hunter-gatherers.

There were different styles of tombs in Britain. Passage graves were common in northern Britain and Ireland. These had narrow stone passages. Long mounds were found in northern Ireland and central Britain. In eastern and south-eastern Britain, people built earthen long barrows. These were often made of wood because stone was rare. The Medway Megaliths are one of these regional groups.

What do the Medway Megaliths look like?

Today, the Medway Megaliths are mostly ruins. But when they were new, they were huge and impressive. They are the most south-easterly group of stone monuments in Britain. They are also the only large stone group in eastern England. Experts like Paul Ashbee called them "the most grandiose and impressive structures" in southern England. The BBC Countryfile website says they are "really quite impressive" as a group. They are like "the east of England's answer to the megaliths of the Salisbury Plains."

The monuments are in two main groups. One is west of the River Medway. The other is on Blue Bell Hill to the east. The two groups are about 8 to 10 kilometers apart. The western group includes Coldrum Long Barrow, Addington Long Barrow, and Chestnuts Long Barrow. The eastern group has Kit's Coty House, Lower Kit's Coty House, and the Coffin Stone. We don't know if they were all built at the same time. We also don't know if they all had the same purpose.

All the Medway long barrows followed a similar plan. They were all lined up from east to west. Each had a stone chamber at the eastern end. They probably had a stone front at the entrance. The chambers were built from sarsen stone. This stone is very hard and strong. It is found naturally in Kent. Builders would have found these stones nearby. Then they moved them to the building site.

These shared features show that people in this area worked together. They were taller than most other tombs in Britain. Some were up to 10 feet high inside. But each monument also had its own unique features. For example, Coldrum is rectangular. Chestnuts has a special front. This might be because the tombs were changed over time.

It seems the builders were inspired by other tombs they knew. We don't know if these builders were local or moved to the Medway area. Experts have suggested ideas about where the style came from. Some think it was from the Low Countries or Scandinavia. Others suggest Germany or the Cotswold-Severn group. Paul Ashbee said it's "impossible to indicate" a precise origin. But he stressed that these megaliths are part of a bigger European tradition.

Not many things have been found inside the tombs. This is because they have been damaged. Human bones were found in Coldrum, Addington, and the Coffin Stone. Burned bones were found at Chestnuts. Pottery pieces were found at Chestnuts, Addington, and Kit's Coty. This suggests they were used as tombs for many people.

Some experts think the area around the megaliths was a "ritual landscape." This means people thought it had special powers. This might be why they built the monuments there. The monuments might have been placed to point towards the Downs or the River. Views from the monuments were not all the same. If the area was cleared of trees, Kit's Coty, Little Kit's Coty, and Coldrum would have had wide views.

Other ancient activity nearby

Other signs of Neolithic life have been found near the megaliths. Digs in the late 1990s found a Neolithic longhouse near the White Horse Stone. It was like longhouses from Europe, built around 5,000-6,000 BCE. Pottery found there suggests people used the site for a long time. We don't know if the longhouse was for living or for rituals. But excavators thought it was probably a home for a group of people.

A large causewayed enclosure was also found at Burham. It has two circular ditches. It covers 5 hectares, making it the biggest in Kent. It was used from about 3700 to 3400 BCE.

The Medway Megaliths are not the only ancient mounds in Kent. Another group of long barrows is near the Stour valley. These include Julliberrie's Grave. The Stour monuments are different because they don't use large stones. They are non-megalithic. This was probably a choice, as stones were available there.

Later history of the sites

People continued to use the land around the Medway megaliths for special purposes. This happened throughout later prehistory. There were rich Bronze Age burials and gold found from the Late Bronze Age. An Iron Age cemetery was also found. In the Middle Ages, the Pilgrim's Way path was built near the megaliths.

In the late 1200s, the Medway Megaliths were damaged on purpose. Some chambers were completely knocked down. Others were left standing. We don't know exactly why this happened. Some think it was because the Christian Church wanted to stop non-Christian beliefs. New churches built nearby might have been part of this plan.

How archaeologists study the megaliths

"The many perspectives of the Medway's stone-built long barrows... are conditioned by the nature of the inevitable progress of knowledge."

From the late 1500s, people called antiquarians started writing about the Medway Megaliths. Some megaliths were damaged or destroyed in the 1800s. They might have been broken up for building materials.

Later, archaeologists took over from antiquarians. In 1871, E.H.W. Dunkin wrote about the monuments. George Klint included them in his 1908 book on Kent. He showed early photos and said they were from the Neolithic period. In 1924, O.G.S. Crawford gave more details about the sites.

In 1982, Robin Holgate wrote a paper about the stones. He said that digging at each site was needed to understand them better. From 1998 to 1999, the Oxford Archaeological Unit dug near the White Horse Stone. This was before the Channel Tunnel Rail Link was built.

From 2006 to 2012, archaeologist Paul Garwood led a project. His team mapped the area around the megaliths. In 2007-2008, Sian Killick studied how the tombs looked from different parts of the landscape.

Modern beliefs and folklore

Some modern Pagan religions use the Medway Megaliths. Druids are one group. In 2014, a Druid group called Roharn's Grove held ceremonies there. Heathen groups also used the sites.

Scholar Ethan Doyle White studied how Pagans use the megaliths. He found that they connect the sites to ancestors. They also see them as sources of "earth energy." Pagans see Neolithic people as their "spiritual ancestors." Since the sites were tombs, they held the remains of the dead. These dead were also seen as ancestors. Heathens often see this ancestry as genetic. Druids focus on a spiritual connection to "ancestors of the land." Pagans also believe the megaliths are on "ley lines" of earth energy.

The western stones: Coldrum, Addington, and Chestnuts

Coldrum Long Barrow: The best preserved

Coldrum Long Barrow is also known as the Coldrum Stones. It is near the village of Trottiscliffe. It sits on a small ridge facing east. The tomb is about 20 meters long. It is wider at the eastern end, about 19 meters.

This is the best-preserved of the Medway Megaliths. But it has still been damaged. Especially on its eastern side, where stones have fallen.

The name "Coldrum" comes from a nearby farmhouse. In the 1800s, people found skulls near the tomb. In 1845, it was wrongly called a stone circle. In 1856, John Mitchell Kemble dug at the site. He found pottery pieces.

The first map of the monument was made in 1871. The first photo was published in 1893. In 1910, F.J. Bennett dug there. He found the bones of 22 people. He also found a pot piece and a flint saw. More bones were found in 1922. But many were lost during World War II. In 1926, the monument was given to The National Trust. It was made a memorial to a local historian. Local stories say the Coldrum Stones are "countless stones" that can't be counted. You can visit the site for free.

Addington Long Barrow: A road runs through it

Addington Long Barrow is north of the church in Addington. You can reach it from the A2 road. This monument is about 60 meters long. It gets narrower from east to west. The stone chamber was at the eastern end, but it has fallen down. A road now cuts through the middle of the monument. The mound is currently one meter high. It would have been much taller originally.

The first mention of stones here was in 1719. In 1779, it was wrongly called a stone circle. In 1827, when the road was made wider, some stones were moved. Around 1845, a local vicar dug at the site. He supposedly found pottery and human bones. A local man believed there was gold buried there.

Edwin Dunkin made a map of the site in 1871. Augustus Pitt-Rivers made a more accurate map in 1878. In 1981, the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit (KARU) surveyed the monument. In 2007, rabbit burrows damaged the road. During repairs, a new stone was found. Digs in 2007 and 2010 found more buried stones. The site is on private land, but you can see it from the road.

Chestnuts Long Barrow: A huge chamber

Chestnuts Long Barrow is near Addington long barrow. The earth mound is gone now. But the eastern end is still marked by large stones. Some of these stones have been put back in their original places. The mound was probably 20 meters long and 15 meters wide. The chamber inside was huge. It was 12 feet long, 7 feet wide, and 9 feet high. Human bones, burned bones, flint tools, and pottery were found inside.

The first clear mention of Chestnuts Long Barrow was in 1773. It was wrongly thought to be a stone circle. In 1778, John Thorpe wrongly linked it to ancient druids. It wasn't until 1863 that someone realized it was a chambered tomb. The site was dug up in 1957 by John Alexander. This was because a house was being built nearby. Bones and other things found were put in Maidstone Museum. Much of this was destroyed in a fire in the 1980s. In 1981, the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit surveyed the monument.

The barrow is on private land. You can visit it for a small fee.

The eastern stones: Kit's Coty, Little Kit's Coty, Coffin Stone, and others

Kit's Coty House: A famous monument

Kit's Coty House is what's left of another chambered tomb. It's probably the most famous monument in Kent. The long earth mound has worn away. Only a dolmen remains at the eastern end. This dolmen has three large upright stones and a capstone on top. In 1982, traces of the mound were found. It was about 70 meters long and 1 meter high.

Archaeologist Paul Garwood said the chamber is similar to ones in western Britain. His team studied the site from 2009 to 2012. They found that the chamber was not directly connected to the mound. It might have been built before the mound. They also found that the mound was built in at least two stages.

Kit's Coty House has been noticed since the 1500s. In the late 1500s, antiquarians like William Lambarde wrote about it. Lambarde compared it to Stonehenge. He thought it was built for Catigern, an ancient British figure. He also said it was linked to the mythical hero Horsa. Samuel Pepys even visited it in 1669.

Antiquarian John Aubrey wrote about it in his book. William Stukeley visited in 1722. He made drawings and plans. In 1722, a local story said the monument was for two Kentish kings who died in battle.

In 1886, Augustus Pitt Rivers visited Kit's Coty. He saw it was being damaged by farming and graffiti. He made it a protected monument in 1885. An iron fence was put around the chamber. In 1946, a local story said three witches built the dolmen. A fourth witch helped put the capstone on top. Today, the monument has iron railings around it. Many tourists visit it.

Little Kit's Coty House: The Countless Stones

Little Kit's Coty House is also called Lower Kit's Coty House. It's about 3 kilometers north-east of Aylesford. You can always visit it, but it's inside iron railings. It has about 21 stones of different sizes.

Antiquarian John Aubrey knew about Little Kit's Coty. William Stukeley also studied it. He said it was once a chambered tomb. He heard that many stones were pulled down in the late 1600s. By the early 1800s, people wrongly linked it to druids. By the mid-1800s, it was called "the Countless Stones." This name came from a local story. In 1887, it became a protected ancient monument.

Folklorist Leslie Grinsell thought it got the name "Countless Stones" after it was damaged around 1690. The story says an Aylesford baker tried to count the stones. He put a loaf of bread on each one. But one loaf disappeared, and the Devil appeared. The baker tried to count the loaves again. He had one more than he started with. As he was about to say the number of stones, he died. In 1976, Grinsell saw numbers chalked on the stones. This showed the story was still believed.

Coffin Stone: A mysterious sarsen

The Coffin Stone is about 400 meters north-west of Little Kit's Coty House. It's also near the Pilgrims Way.

The Coffin Stone is a rectangular sarsen stone. It is about 4.40 meters long and 2.80 meters wide. It is at least 50 centimeters thick. Archaeologists Brian Philp and Mike Dutto thought it marked a chambered long-barrow. They saw an outline of a mound. Two smaller stones are nearby. Another stone was moved on top of the Coffin Stone by a farmer in 1980.

Stukeley mentioned the stone in 1776. In the 1840s, an antiquarian said a sack of human bones was found near the stone in the 1830s. Edwin Dunkin said in 1871 that a hedge was removed in 1836. This revealed the stone, two human skulls, bones, and charcoal.

In 2008 and 2009, Garwood's team dug at the site. They found that the sarsen was placed there much later, between 1450 and 1600 CE. So, it was not a fallen stone from an ancient tomb. However, Garwood suggested it might have been a standing stone (monolith) in earlier times. He pointed to a large hollow nearby. This hollow was similar to places where stones were taken from at other ancient sites.

Smythe's Megalith: A lost tomb

Another chambered tomb once existed in a large field. It is sometimes called Smythe's Megalith. In 1823 or 1824, a landowner found large stones under the soil. They were making farming difficult. When he tried to remove them, he found three upright stones. He asked historian Clement Taylor Smythe to investigate. Smythe's dig found a rectangular stone chamber. It held the bones of at least two adults and a piece of pottery. Nothing of this monument is visible today. From the description, it was like the other Medway Megaliths. It was lined up east-west. The chamber was at the eastern end of a long barrow.

The White Horse Stones: A folk tale connection

The Upper White Horse Stone is in a narrow wooded area. You can reach it from the Pilgrim's Way path. This stone stands upright. It is 2.90 meters long, 1.65 meters high, and 60 centimeters wide. Nine smaller stones stretch west from it. These might be parts of a chambered tomb. But there is no mound. They might also be stones moved by farmers. About 300 meters west, there was another large stone. It was called Lower White Horse Stone. But it was destroyed in the 1820s. Its site is probably under the main road now.

A local story from the early 1800s links the White Horse Stone to the Battle of Aylesford in 455. It says Hengist and Horsa flew a banner with a White Horse. This banner was found near or under the White Horse Stone. Paul Ashbee thought this story was probably from the 1600s. He said much of the folklore about the White Horse Stone was originally about the Lower White Horse Stone. It moved to the Upper one after the Lower one was destroyed.

Other possible tombs

In 1980, a farmer found two large buried stones. This was near the eastern group of tombs. Digs found four more medium-sized stones buried in pits. The archaeologists thought this might be another chambered long barrow.

See also

In Spanish: Megalitos de Medway para niños

In Spanish: Megalitos de Medway para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |