Lancaster Canal Tramroad facts for kids

The Lancaster Canal Tramroad was a special kind of railway. It was finished in 1803. People also called it the Walton Summit Tramway or the Old Tram Road. Its main job was to connect the two ends of the Lancaster Canal. These two parts of the canal were separated by the River Ribble valley. The plan was to build a canal link later, but it never happened.

Contents

Building the Tramroad: A Temporary Fix

The Lancaster Canal Company got permission in 1792 to build a canal. This canal would link towns like Kendal, Lancaster, and Preston. It would also connect them to coal mines near Wigan. Coal was important for moving north. Limestone was important for moving south.

Most of the canal was built quickly. This included a huge aqueduct over the River Lune near Lancaster. But building across the wide River Ribble valley was too hard. The company ran out of money before they could finish it.

The first idea was to build a big stone aqueduct over the river. It would also need up to 32 locks to finish the route. But as a temporary solution, the canal company built the tramroad. This allowed boats to move goods between the two canal halves. It took three years to build.

How the Tramroad Worked

In 1794, the canal company hired William Cartwright. He helped build the Lune Aqueduct. Later, he was in charge of building the tramroad. Other famous engineers, John Rennie and William Jessop, were busy elsewhere. So, William Cartwright was fully responsible for the tramroad. His old house in Preston is still there today.

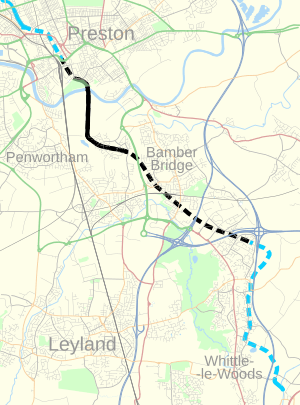

The tramroad was about five miles long. It had two tracks, like a double road. But there was a short part with only one track. This was in a tunnel under Fishergate in Preston. The iron rails were shaped like an "L". They were nailed to big limestone blocks. The wagons had wheels without flanges. The "L" shape of the rails kept the wheels on the track. The distance between the rails was about 4 feet 3 inches (1295 mm).

Horses pulled the wagons. Sometimes, up to six horses pulled one wagon. Each wagon could carry two tons of goods. At first, there were three sloped sections called "inclined planes." Here, wagons were pulled up or down by stationary steam engines using a continuous chain.

The tramroad crossed the River Ribble on a wooden bridge. This bridge lasted almost 100 years longer than the tramroad itself. In the 1960s, a new concrete bridge was built. It looked just like the old wooden one.

There were many accidents on the tramroad. Many of them happened on the inclined planes. Wagons would sometimes run away down the slopes.

People who owned wagons were called "halers." They paid the company a fee to use the tramroad. This was common on early railways. John Procter was the last haler. He worked on the tramroad for 32 years. He walked the 10-mile round trip twice a day. It's thought he walked or rode nearly 200,000 miles during his career! He even needed his clogs fixed once a week.

Why the Tramroad Closed

In 1813, people thought about replacing the tramroad with a canal. But it would cost too much money, about £160,000. This was too expensive for the company.

In 1831, the Preston and Wigan Railway was built. This was bad news for the tramroad. People suggested turning the tramroad into a railway. Or maybe it could join the new railway company. But this never happened. The tramroad got caught up in the railway business of the time.

In 1837, the new Bolton and Preston Railway rented the tramroad. They wanted it as a way to get into Preston. This would help them avoid a rival railway. But the two companies made a deal before this was needed. Still, the Bolton and Preston Railway ended up owning the tramroad.

In 1844, the Bolton and Preston Railway joined with the rival North Union Railway. Soon after, a new railway line was built to the canal basin in Preston. This meant coal from Wigan could come directly to Preston by train. The tramroad was no longer needed.

The North Union Railway wanted to close the tramroad right away. But the canal company said no. So, the railway had to keep it open, even though it was falling apart. In 1864, a new law allowed the canal north of Preston to be rented to the railway. The part south of Walton Summit was rented to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. This law also allowed the tramroad to close between Preston and Bamber Bridge.

In 1872, some land was exchanged. The part of the tramroad between Preston and Carr Wood became a public path. This included the tramroad bridge over the River Ribble. It is still a footpath today.

Another law in 1879 allowed the last part of the tramroad to close. This was between Bamber Bridge and Walton Summit. The north end of the canal was eventually sold to the London and North Western Railway. The Lancaster Canal Company officially closed in 1886.

Where You Can Still See Parts of It

A well-preserved section of the track was moved. It was taken from Bamber Bridge and put in Worden Park in Leyland. You can see plates and stone sleepers from the tramroad in the South Ribble Museum in Leyland. The Harris Museum in Preston also has some.

The Harris Museum also has a model of a wagon. They have a wheel and axle from a wagon too. These were found in the River Ribble. They had been there since an accident. A chain broke on a slope, and wagons crashed into the river below.

The tunnel under Fishergate was made bigger after 1885. It is still used today for cars to get to the Fishergate Shopping Centre car park. It used to lead to a goods yard. You can still see part of a support for a bridge over Garden Street.

A path on the north side of Avenham Park follows the old tramway route. It goes down a slope and across a footbridge over the River Ribble. This bridge is where the original wooden bridge was. The footpath continues along the riverbank.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |