Laura Smith Haviland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Laura Smith Haviland

|

|

|---|---|

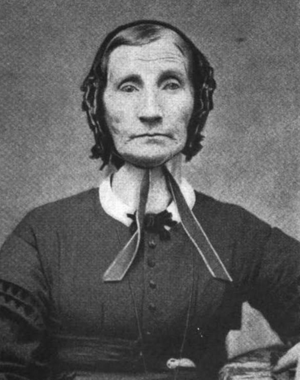

Haviland in 1881

|

|

| Born | December 20, 1808 Kitley Township, Ontario, Canada

|

| Died | April 20, 1898 (aged 89) Grand Rapids, Michigan, U.S.

|

| Occupation | abolitionist, suffragist, temperance worker |

| Spouse(s) | Charles Haviland Jr. |

| Children | 8 |

Laura Smith Haviland (December 20, 1808 – April 20, 1898) was an American abolitionist, suffragette, and social reformer. She was a Quaker and a very important person in the history of the Underground Railroad. She worked hard to end slavery, help former slaves, and fight for women's rights.

Contents

Early Life and Quaker Roots

Laura Smith Haviland was born on December 20, 1808, in Kitley Township, Ontario, Canada. Her parents, Daniel and Asenath Smith, were Americans who had moved there. They were Quakers, a religious group known for their simple life and strong beliefs.

Quakers believed in equal education for boys and girls, which was very unusual at that time. They also thought slavery was wrong and cruel. Laura grew up in this environment, learning about fairness and justice from a young age.

In 1815, her family moved back to the United States, settling in Cambria, New York. There wasn't a school nearby, so Laura's mother taught her to spell. Laura loved to learn and read every book she could find.

At 16, Laura married Charles Haviland, Jr., another Quaker. They had eight children together and shared a happy marriage.

Fighting Slavery and Starting a School

Laura had seen African Americans treated badly when she was young. These experiences, along with books she read, made her strongly against slavery.

In 1832, Laura and others helped start the Logan Female Anti-Slavery Society in Michigan. This was the first group in Michigan dedicated to ending slavery.

Five years later, in 1837, Laura and Charles started a school called the Raisin Institute. It was a "manual labor school" for children who didn't have much money. Laura taught the girls household skills, while Charles taught the boys farm work. The Havilands insisted that the school welcome all children, no matter their race, religion, or gender. This made it the first racially integrated school in Michigan. At first, some white students didn't want to study with African American children, but Laura said their differences "soon melted away."

As the Havilands became more involved in fighting slavery, some other Quakers disagreed with their active approach. In 1839, Laura and her family left the Quaker group to join the Wesleyans, who also strongly supported ending slavery.

In 1845, a terrible illness took the lives of six of Laura's family members, including her parents, her husband, and her youngest child. Laura herself got sick but survived. She was 36, a widow with seven children, and had a farm and the Raisin Institute to manage. Two years later, her oldest son also died. Because of money problems, the Raisin Institute had to close in 1849.

Despite these sad losses, Laura kept working against slavery. In 1851, she helped create the Refugee Home Society in Windsor, Ontario, Canada. This group helped former slaves settle in Canada, providing them with a church, a school, and land to farm. Laura even stayed there for several months to teach.

By 1856, Laura had raised enough money to reopen the Raisin Institute. The school now included talks by former slaves about their experiences. In 1864, the Institute closed again because many staff and students joined the Civil War.

Helping on the Underground Railroad

In the 1830s, the Haviland family started hiding runaway slaves on their farm. Their home became the first "station" of the Underground Railroad in Michigan. After her husband died, Laura continued to shelter runaway slaves. Sometimes, she even took them to Canada herself. She was a key leader in the Detroit part of the Underground Railroad.

Laura also traveled to the Southern states many times to help slaves escape. In 1846, she went to Tennessee to try and free the children of Willis and Elsie Hamilton, who were former slaves. The children were still held by their mother's old slave owner.

The slave owner, John P. Chester, tried to trick the Hamiltons into returning. Laura, suspecting a trap, went in their place with her son and a student. Chester was furious when he realized Laura was not Willis Hamilton. For 15 years, Chester tried to get revenge on Laura, even sending slave catchers after her.

Later, after the Fugitive Slave Law was passed, the Chester family tried to have Laura arrested for "stealing" their slaves. If found guilty, Laura could face big fines and prison. Luckily, the judge in her case was sympathetic to abolitionists. He delayed her case, which allowed Laura to help the Hamiltons escape to Canada. Laura avoided punishment.

Laura made other successful trips south that she didn't write about in her book. Sometimes, she pretended to be a white cook or even a light-skinned free person of color. She visited plantations and helped slaves escape to the North.

Civil War and Helping Freed People

During the American Civil War, Laura visited many refugee camps and hospitals, even going to the battle lines. She gave supplies to people who had lost their homes, to freed slaves, and to soldiers.

In 1865, General Oliver Otis Howard, who led the new Freedmen's Bureau, made Laura an Inspector of Hospitals. But her job was much bigger than just inspecting hospitals. For two years, she traveled through different states, giving out supplies, reporting on how freed slaves and poor white people were living, setting up refugee camps, starting schools, working as a nurse, and giving public talks.

To help white people understand what slavery was like, she visited old plantations. She collected chains, irons, and other tools that had been used on slaves. Laura brought these items North and showed them during her talks. She also met with President Andrew Johnson to ask him to free former slaves who were still in Southern prisons for trying to escape years before.

While working at a hospital in Washington, D.C., Laura became friends with Sojourner Truth, another famous abolitionist.

The Haviland Home Orphanage

After the Civil War, the Raisin Institute was renamed the Haviland Home. It became an orphanage for African American children. Laura brought 75 homeless children from Kansas to live there. As more children arrived, some white people in Michigan became worried. They said Laura was costing taxpayers too much money and demanded the orphanage close.

In 1867, a group bought the orphanage and closed it, leaving the orphans without a home. Laura stopped her work in Washington, D.C., and returned to Michigan to help the children. She collected enough donations to buy the orphanage herself and managed it. By 1870, money was very scarce. Laura asked the state to take over the orphanage, and it became the Michigan Orphan Asylum.

Later Years and Legacy

When the Reconstruction period ended in 1877, many African Americans left the South because they faced attacks from racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Thousands of people crowded into refugee camps in Kansas. Laura was determined to help. She traveled to Washington, D.C., and spoke about the terrible conditions in the camps. Then, she went to Kansas with supplies for the refugees. Using her own savings, Laura bought 240 acres (about 1 square kilometer) of land in Kansas for the freed people to live and farm on.

Laura Haviland not only fought against slavery and helped freed people, but she also worked for other important causes. She supported women's suffrage, which meant women getting the right to vote. She also helped start the Woman's Christian Temperance Union in Michigan, which worked to reduce alcohol use.

Laura Haviland died on April 20, 1898, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She is buried next to her husband in the Raisin Valley Cemetery in Adrian, Michigan. At her funeral, white and African American singers sang hymns, and both white and African American people carried her casket to the grave. This showed the unity she had worked for throughout her life.

Honoring Laura Haviland

- The town of Haviland, Kansas is named after her.

- A statue of Laura Haviland stands in front of the Lenawee County Historical Museum in Adrian, Michigan. The words on the statue say: "A Tribute to a Life Consecrated to the Betterment of Humanity."

- Laura Smith Haviland Elementary School in Waterford, Michigan is named in her honor.

- Laura Smith Haviland was added to the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum in Peterboro, New York in 2018.

See also

In Spanish: Laura Smith Haviland para niños

In Spanish: Laura Smith Haviland para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |