Lexington–Concord Sesquicentennial half dollar facts for kids

| United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1925 |

| Mintage | 162,099 including 99 pieces for the Assay Commission |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at Philadelphia Mint without mint mark. |

| Obverse | |

|

|

|

| Design | The Minute Man by Daniel Chester French, Concord, Massachusetts |

| Designer | Chester Beach |

| Design date | 1925 |

| Reverse | |

|

|

|

| Design | Old Belfry, Lexington, Massachusetts |

| Designer | Chester Beach |

| Design date | 1925 |

The Lexington–Concord Sesquicentennial half dollar is a special fifty-cent coin made in 1925. It was created by the U.S. Mint to celebrate 150 years since the Battles of Lexington and Concord. These battles, fought on April 19, 1775, were the very beginning of the American Revolutionary War. This coin is also known as the Lexington–Concord half dollar or the Patriot half dollar. It was designed by a talented artist named Chester Beach.

Lawmakers from Massachusetts asked Congress to approve this special coin in 1924. The bill passed through Congress and was signed by President Calvin Coolidge. Chester Beach had to make sure both the towns of Lexington and Concord liked his designs. The Commission of Fine Arts also had to approve it.

These coins were sold for $1 each at the anniversary celebrations in Lexington and Concord. They were also available at banks across New England. Even though fewer than half of the planned 300,000 coins were made, almost all of the ones that were struck were sold. Today, depending on how good their condition is, these coins can be worth hundreds of dollars to collectors.

Contents

What Started the American Revolution?

The Battles of Lexington and Concord happened in two towns in Massachusetts on April 19, 1775. Before the American Revolutionary War began, there was a lot of tension between the British government and the American colonies. By early 1775, groups of local fighters, called minutemen, had formed around Boston. They were ready to fight the British at a moment's notice. These groups stored weapons and supplies in towns like Concord.

The British commander in Boston, General Thomas Gage, was told to stop this resistance. On April 18, 1775, General Gage secretly ordered Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith to take 700 soldiers to Concord. Their mission was to destroy the American supplies there. It's not clear how the Americans found out about the plan. Some think General Gage's wife, who was from New Jersey, might have been a spy.

Another American leader, Joseph Warren, quickly told Paul Revere and William Dawes. These two men rode on different paths to Lexington to warn local leaders and the militia. They both reached Lexington and met with important figures like John Hancock and Samuel Adams. Thanks to their warnings, the supplies in Concord were moved to safety.

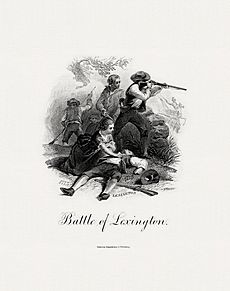

The First Shots Fired

British troops started their march at 2 AM on April 19. Major John Pitcairn led some troops ahead. When Pitcairn and his men arrived at Lexington's town common, they found a group of armed colonists. Pitcairn ordered them to leave. In the confusion, a shot was fired from an unknown source. This led to the British soldiers firing many shots. Eight local men were killed, and one British soldier was wounded.

The British then went to Concord and destroyed what supplies they could find. A second fight happened at the Old North Bridge. This is where the famous "shot heard round the world" was fired. About 400 minutemen had gathered by then. When they saw smoke from Concord, they thought the town was burning. They tried to cross the bridge to help. The British fired at them, but the colonists fired back and won this small battle.

The British, now with more soldiers, began their march back to Boston. But at least 2,000 militiamen kept attacking them with gunfire along the way. The British suffered many losses until they reached the safety of cannons near Boston. These encounters at Lexington and Concord were the very first battles of the Revolutionary War.

How the Coin Was Approved

In 1924, members of Congress from Massachusetts wanted to create a special coin for the 150th anniversary of the battles. Congressmen John Jacob Rogers and Frederick Dallinger introduced bills to make this happen. Rogers represented Concord's area, and Dallinger represented Lexington's.

They asked for a commission to be set up, with members chosen by Congress and President Calvin Coolidge. They also wanted $10,000 for the commission and approval for special coins and stamps. Rogers explained that the idea for the coin came from a similar bill for the Pilgrim Tercentenary half dollar (1920–1921).

At that time, the government didn't sell commemorative coins directly. Instead, Congress chose an organization that could buy the coins at their face value (50 cents) and sell them to the public for more (like $1). The goal was to make up to 300,000 coins. The congressmen pointed out that the government would actually make money from these coins. This is because they would profit from the difference between the coin's value and its production cost, and collectors would keep the coins, so the government wouldn't have to pay them back.

The bill passed easily in the House of Representatives. It then went to the Senate and was approved there too. President Coolidge signed the bill into law on January 14, 1925. This meant the Lexington–Concord half dollar could be made!

Designing the Special Coin

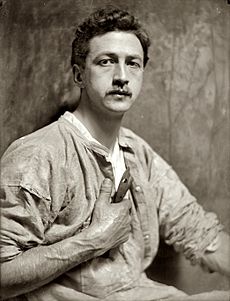

In 1923, both Lexington and Concord committees thought about having a special coin. They both contacted Chester Beach, who had designed the Monroe Doctrine Centennial half dollar. Beach convinced them to work together. They agreed to split his fee of $1,250. Each town would choose the design for one side of the coin.

The Concord committee suggested the design for the front (obverse) of the coin. The Lexington committee suggested the design for the back (reverse). Chester Beach needed the United States Commission of Fine Arts to approve his plaster models before he could get paid. He learned that the Mint would take a few weeks to start making the coins once the final approval was given.

The towns wanted specific words on the coin. For example, they wanted "THE CONCORD MINUTE MAN" to appear on the coin, even if it was hard to read. This was important to avoid any disagreements between the two towns. The Commission of Fine Arts thought the statue of the Minuteman might be too narrow for a coin. But they still approved the design, saying that a designer should be allowed to use symbols as they see fit for a coin. By late March 1925, test coins were being made at the Philadelphia Mint.

What Do the Coin Designs Show?

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April's breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.

The front (obverse) of the coin shows a statue called The Minute Man. This statue was created by Daniel Chester French in 1874 and stands in Concord. It honors the minutemen, who were volunteer soldiers ready to fight the British in 1775. The coin shows a farmer holding a rifle, with his coat draped over his plow. He is ready to answer the call to assemble, perhaps from the bell in the Old Belfry in Lexington.

The minuteman's head on the coin covers part of the country's name, "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA." To his left are the words "CONCORD MINUTE-MAN," and to his right is "IN GOD WE TRUST." The actual statue in Concord has the first part of a famous poem called "Concord Hymn" by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Many American schoolchildren used to memorize these lines.

The back (reverse) of the coin shows the Old Belfry, which is in Lexington. A bell in this belfry was rung to call the local militia together. The belfry wasn't old when it was built in 1761. The bell was rung after Paul Revere and William Dawes arrived. Captain John Parker sent his men home when no British soldiers appeared, but told them to stay ready. The bell was rung again at 5:30 AM when news came that the British were close.

Some coin experts have shared their thoughts on the design. John F. Jones, a coin expert, thought the statue and belfry were good choices for the coin. However, he felt the coin lacked the sharp details of earlier special coins. Art historian Cornelius Vermeule thought the coin didn't show much of Beach's original artistic skill. He also didn't like the many words on the coin, especially "In God We Trust" in that spot.

How the Coins Were Made and Sold

A total of 162,099 Lexington–Concord Sesquicentennial half dollars were made at the Philadelphia Mint in April and May 1925. Ninety-nine of these coins were set aside for testing by the 1926 Assay Commission. Interestingly, these coins were made from blank metal pieces that were originally meant for a different coin, the 1924 Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar.

The very first coin made was given to President Coolidge. The half dollars were sold at the anniversary celebrations in Lexington and Concord, which took place from April 18–20, 1925. About 39,000 coins were sold in Lexington and 21,000 in Concord. The Lexington Trust Company and the Concord National Bank handled the sales. They sold the coins in special wooden boxes decorated with images of the statue and belfry.

These coins were also sold by banks throughout New England and in some other parts of the country. Only 86 coins were sent back to the Mint, likely because they were damaged. Most of these coins were sold to the general public, not just to coin collectors. The original price was $1. Today, a coin guide from 2018 lists the half dollar as being worth between $75 and $700, depending on its condition. One amazing coin even sold at an auction in 2014 for $11,880!

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |