Lowell mill girls facts for kids

The Lowell mill girls were young women who worked in the large textile factories in Lowell, Massachusetts. This happened during the Industrial Revolution in the United States, a time when new machines changed how things were made. Most of these workers were young women, often from New England farms, usually aged 15 to 35. By 1840, at the peak of the textile boom, Lowell's factories employed over 8,000 workers. Almost three-quarters of them were women.

These young women came to work in the mills for different reasons. Some wanted to help their brothers pay for college. Others sought educational chances offered in Lowell. Many also wanted to earn extra money for their families. Francis Cabot Lowell, who started these factories, wanted to provide good housing and education. He aimed to create a better environment than the harsh British mills, which were known for their poor conditions.

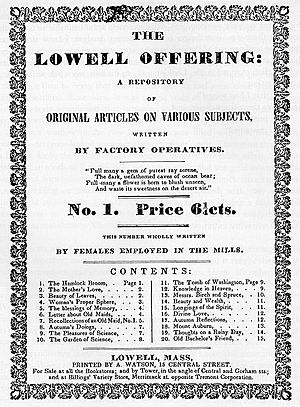

Even though women earned about half of what men did, many gained financial independence for the first time. They earned around three to four dollars per week. Boarding costs were about 75 cents to $1.25, leaving them money for clothes, books, and savings. The girls formed book clubs and even published their own magazines, like the Lowell Offering. This magazine let them share stories about their lives in the mills. Working in the factories also helped these women challenge traditional gender roles.

Over time, adult women replaced child workers, as factory owners like Lowell preferred not to hire children. As the factory system grew, many women joined the larger American labor movement. They protested against increasingly tough working conditions. A historian named Philip Foner noted that they "succeeded in raising serious questions about woman’s so-called ‘place’."

In 1845, after several protests, many workers formed the first union for working women in the U.S. It was called the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. This group started a newspaper called the Voice of Industry. In it, workers wrote strong criticisms of the new factory system. This newspaper was very different from other literary magazines published by female workers.

Contents

How Lowell Became an Industrial City

In 1813, a businessman named Francis Cabot Lowell started the Boston Manufacturing Company. He built a textile mill next to the Charles River in Waltham. Before this, some factories only did part of the cloth-making process, like carding and spinning. Weaving was often done by hand on nearby farms. But Lowell's Waltham mill was different. It was the first "integrated" mill in the United States. This meant it could turn raw cotton into finished cloth all in one building.

In 1821, Lowell's business partners wanted to make their textile operations even bigger. They bought land near the Pawtucket Falls on the Merrimack River. This area became the town of Lowell in 1826. By 1840, the textile mills there employed almost 8,000 workers. Most of these were women aged 15 to 35.

Lowell quickly became known as the "City of Spindles." It was a key center of the Industrial Revolution in America. New, large machines were rapidly developed for making cloth. At the same time, new ways of organizing workers for mass production were also created. These changes led to huge increases in production. Between 1840 and 1860, the number of spindles used went from 2.25 million to almost 5.25 million. The amount of cotton used jumped from 300,000 bales to nearly 1 million. The number of workers grew from 72,000 to almost 122,000.

This huge growth meant big profits for the textile companies. For example, between 1846 and 1850, the investors from Boston who founded Lowell earned an average of 14% profit each year. Most companies made similar high profits during this time.

Life and Work in the Mills

The social standing of factory girls had been looked down upon in places like France and England. Harriet Hanson Robinson, who worked in the Lowell mills from 1834 to 1848, wrote about this. She suggested that high wages were offered to women to encourage them to become mill girls. This was done despite the negative views that still existed about this type of work.

Factory Conditions

The Lowell System combined large machines with an effort to improve the standing of its female workers. A few girls came with their mothers or older sisters and were as young as ten. Some were middle-aged. But the average age was about 24. Workers were usually hired for one-year contracts, and they stayed for about four years on average. New workers started with various tasks and were paid a set daily wage. More experienced loom operators were paid based on how much they produced. New workers were trained by older, more experienced women.

Conditions in the Lowell mills were very tough by today's standards. Employees worked from 5:00 am until 7:00 pm, about 73 hours per week. Each room usually had 80 women working at machines. Two male overseers managed the work. The noise from the machines was described by one worker as "something frightful and infernal." Even though the rooms were hot, windows were often kept closed in summer. This was to keep conditions perfect for the thread work. The air was also full of tiny pieces of thread and cloth.

Charles Dickens visited in 1842 and spoke positively about the conditions. He said he didn't see any young girl who looked unhappy. He felt that if she had to earn a living by hand, he wouldn't move her from those factories. However, many workers worried that visitors were shown a cleaned-up version of the mills. They felt the companies used the image of "literary workers" to hide the harsh reality of factory life. One worker named Juliana wrote in the Voice of Industry that it was a "very pretty picture," but "we who work in the factory know the sober reality to be quite another thing altogether." The "sober reality" was 12 to 14 hours of dull, tiring work. Many workers felt this work made it hard to learn or think deeply.

Living Quarters

The factory owners built hundreds of boarding houses near the mills. Textile workers lived in these houses all year. A curfew of 10:00 pm was common, and men were generally not allowed inside. About 26 women lived in each boarding house, with up to six sharing a bedroom. One worker described her room as "a small, comfortless, half-ventilated apartment containing some half a dozen occupants." Life in these boarding houses was usually strict. Widows often ran the houses and watched the workers closely. Church attendance was required for all the girls.

Trips away from the boarding house were rare. The Lowell girls worked and ate together. However, half-days and short paid vacations were possible because of the piece-work system. One girl could work another's machines in addition to her own, so no wages would be lost. These close living conditions created both community and sometimes disagreements. Older women helped new workers learn about dress, speech, behavior, and the community's ways. The women became very close because they spent so much time together, both at work and after work. They often did cultural activities like music and reading.

Workers often encouraged their friends or relatives to come work in the factories. This created a family-like feeling among many of the workers. The Lowell girls were expected to go to church and act morally, as was proper for society. The 1848 Handbook to Lowell stated that the company would "not employ anyone who is habitually absent from public worship on the Sabbath, or known to be guilty of immorality."

Learning and Thinking in the Mills

For many young women, Lowell was appealing because of the chances to study and learn more. Most had already finished some schooling and were eager to improve themselves. When they arrived, they found a lively intellectual culture among the working class. Workers read a lot in Lowell's city library and reading rooms. They also joined large, informal "circulating libraries" that lent out novels. Many even tried writing their own stories and poems. Breaking factory rules, workers would attach poems to their spinning machines to "train their memories." They would also pin up math problems in their workrooms. In the evenings, many took courses offered by the mills. They also attended public lectures at the Lyceum, a theater built by the company. The Voice of Industry newspaper often listed upcoming lectures, courses, and meetings on topics from astronomy to music.

The companies were happy to show off these "literary mill girls." They boasted that these were the "most superior class of factory operative," impressing visitors from other countries. But this hid the strong dislike many workers felt for the 12–14 hours of tiring, repetitive work. They saw this work as harmful to their desire to learn. As one worker asked in the Voice, "who, after thirteen hours of steady application to monotonous work, can sit down and apply her mind to deep and long-continued thought?" Another Lowell worker shared a similar feeling: "I well remember the chagrin I often felt when attending lectures, to find myself unable to keep awake...I am sure few possessed a more ardent desire for knowledge than I did, but such was the effect of the long hour system, that my chief delight was, after the evening meal, to place my aching feet in an easy position, and read a novel."

The Lowell Offering

In October 1840, Reverend Abel Charles Thomas started a monthly magazine for and by the Lowell girls. As the magazine became more popular, women contributed poems, songs, essays, and stories. They often used their characters to talk about their lives and working conditions.

The "Offering" had both serious and funny content. In a letter in the first issue, "A Letter about Old Maids," the writer suggested that "sisters, spinsters, lay-nuns, & c" were an important part of God's plan. Later issues, especially after labor protests in the factories, included an article about the importance of organizing.

Strikes of 1834 and 1836

When the factory owners first tried to hire female textile workers, they offered good wages for that time (three to five dollars per week). But during an economic downturn in the early 1830s, the company leaders suggested cutting wages. This led to organized "turn-outs" or strikes.

In February 1834, the leaders of Lowell's textile mills announced a 15% wage cut, starting March 1. After several meetings, the female textile workers organized a "turn-out" or strike. The women involved in the strike immediately took out their savings. This caused a "run" on two local banks, meaning many people withdrew their money at once.

The strike failed, and within days, all the protesters either returned to work with lower pay or left town. However, this "turn-out" showed how determined the Lowell female textile workers were to take action. This upset the factory managers, who saw the strike as a betrayal of what was considered "feminine." William Austin, a manager at the Lawrence Manufacturing Company, wrote to his bosses that "a spirit of evil omen...has prevailed, and overcome the judgment and discretion of too many."

Again, because of a serious economic downturn and high living costs, the leaders of Lowell's textile mills increased the textile workers' rent in January 1836. This was to help the company boarding housekeepers. As the economic problems continued in October 1836, the Directors suggested another rent increase for workers living in company boarding houses. The female textile workers immediately protested. They formed the Factory Girls' Association and organized another "turn-out" or strike.

Harriet Hanson Robinson, who was an eleven-year-old "doffer" (a worker who removed full bobbins of yarn) during the strike, remembered it in her writings. She said: "One of the girls stood on a pump and gave vent to the feelings of her companions in a neat speech, declaring that it was their duty to resist all attempts at cutting down the wages. This was the first time a woman had spoken in public in Lowell, and the event caused surprise and consternation among her audience."

This "turn-out" attracted over 1,500 workers. This was almost twice the number from two years before. It caused Lowell's textile mills to run far below their normal capacity. Unlike the 1834 strike, there was huge community support for the striking female textile workers in 1836. The proposed rent hike was seen as breaking the written agreement between employers and employees. The "turn-out" lasted for weeks. Eventually, the leaders of Lowell's textile mills canceled the rent increase. Even though the "turn-out" was a success, the weaknesses of the system were clear. These problems got even worse during the Panic of 1837, a major economic crisis.

Lowell Female Labor Reform Association

The strong sense of community among the women, from living and working together, directly helped the first union of women workers grow. This was the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. It started with 12 workers in January 1845. Its membership grew to 500 within six months and kept expanding quickly. The women themselves ran the Association completely. They elected their own leaders and held their own meetings. They helped organize female workers in Lowell and set up branches in other mill towns. They organized fairs, parties, and social gatherings. Unlike many middle-class women activists, these workers found a lot of support from working-class men. These men welcomed them into their reform groups and treated them as equals.

One of the Association's first actions was to send petitions, signed by thousands of textile workers, to the Massachusetts General Court (the state legislature). They demanded a ten-hour workday. In response, the Massachusetts Legislature created a committee. It was led by William Schouler, a representative from Lowell. This committee investigated and held public hearings. During these hearings, workers spoke about factory conditions and the physical demands of their twelve-hour days. These were the first government investigations into labor conditions in the United States. The 1845 committee decided that it was not the state legislature's job to control work hours. The LFLRA called its chairman, William Schouler, a "tool" and worked to make him lose his next election. Schouler lost to another candidate over the issue of railroads. The impact of working men and non-voting working women was very limited. The next year, Schouler was re-elected to the State Legislature.

The Lowell female textile workers kept sending petitions to the Massachusetts Legislature. Legislative committee hearings became an annual event. Although the first push for a ten-hour workday didn't succeed, the LFLRA continued to grow. It joined with the New England Workingmen's Association and published articles in their pro-labor newspaper, the Voice of Industry. This direct pressure forced the leaders of Lowell's textile mills to reduce the workday by 30 minutes in 1847. The FLRA's organizing efforts spread to other nearby towns. In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a law for a ten-hour workday. However, there was no way to enforce it, and workers were often asked to work longer days. By 1848, the LFLRA stopped being a labor reform organization. Lowell textile workers continued to ask for and push for better working conditions. In 1853, the Lowell companies reduced the workday to eleven hours.

The textile industry in New England grew rapidly in the 1850s and 1860s. The companies couldn't find enough Yankee women to fill all the new jobs. So, to get more workers, textile managers turned to people who had recently moved to the United States. Many of these were survivors of the Great Irish Famine. During the Civil War, many of Lowell's cotton mills closed. They couldn't get raw cotton from the South. After the war, the textile mills reopened. They started hiring French Canadian men and women. Even though many Irish and French Canadian immigrants moved to Lowell to work in the textile mills, Yankee women still made up most of the workforce until the mid-1880s.

Fighting for Rights

The Lowell girls' organizing efforts were important for two reasons. First, women were taking part in "unfeminine" activities. Second, they used political ideas to gain public support. They presented their fight for shorter workdays and better pay as a matter of rights and personal dignity. They tried to connect their struggle to the larger ideas of the American Revolution. During the 1834 "turn-out" or strike, they warned that "the oppressing hand of avarice would enslave us." The women included a poem that said:

Let oppression shrug her shoulders,

And a haughty tyrant frown,

And little upstart Ignorance,

In mockery look down.

Yet I value not the feeble threats

Of Tories in disguise,

While the flag of Independence

O'er our noble nation flies.

In the 1836 strike, this idea came back in a protest song:

Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

That I cannot be a slave.

The clearest example of this political message is found in a series of writings published by the Female Labor Reform Association. These were called Factory Tracts. In the first one, titled "Factory Life As It Is," the author declared "that our rights cannot be trampled upon with impunity; that we WILL not longer submit to that arbitrary power which has for the last ten years been so abundantly exercised over us."

This way of thinking about labor activity as connected to American democracy has been very important for other labor campaigns. Noam Chomsky, a professor and social critic, has often mentioned this. He quoted the Lowell mill girls on the topic of wage slavery:

When you sell your product, you retain your person. But when you sell your labour, you sell yourself, losing the rights of free men and becoming vassals of mammoth establishments of a monied aristocracy that threatens annihilation to anyone who questions their right to enslave and oppress.

Those who work in the mills ought to own them, not have the status of machines ruled by private despots who are entrenching monarchic principles on democratic soil as they drive downwards freedom and rights, civilization, health, morals and intellectuality in the new commercial feudalism.

Notable People

- Sarah Bagley

- Eliza Jane Cate

- Betsey Guppy Chamberlain

- Harriet Farley

- Margaret Foley

- Adelia Sarah Gates

- Abba Goddard

- Lucy Larcom

- Francis Cabot Lowell

- Harriet Hanson Robinson

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |