Manapouri Power Station facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Manapōuri Power Station |

|

|---|---|

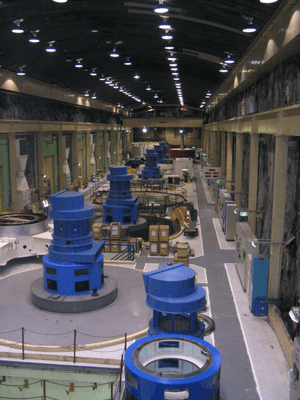

The Manapōuri Power Station machine hall

|

|

|

Location of Manapōuri Power Station in New Zealand

|

|

| Country | New Zealand |

| Location | west end of Lake Manapōuri, Fiordland National Park, Southland |

| Coordinates | 45°31′17″S 167°16′40″E / 45.52139°S 167.27778°E |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | February 1964 |

| Opening date | September 1971 |

| Construction cost | NZ$135.5 million (original station) NZ$200 million (second tailrace tunnel) NZ$100 million (half-life refurbishment) |

| Owner(s) | Meridian Energy |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Manapōuri |

| Catchment area | 3,302 km2 (1,275 sq mi) |

| Surface area | 141.6 km2 (54.7 sq mi) |

| Maximum water depth | 444 m (1,457 ft) |

| Power station | |

| Name | Manapōuri Power Station |

| Type | Conventional |

| Turbines | 7× vertical Francis |

| Installed capacity | 850 MW |

| Capacity factor | 68.4% / 79.7% |

| Annual generation | 5100 GWh |

| Lake Manapōuri is a natural lake - the drop between it and the sea is used by Manapōuri station. |

|

The Manapōuri Power Station is a huge underground power plant in New Zealand. It uses the power of water (called hydroelectricity) to make electricity. You can find it on the western side of Lake Manapōuri in Fiordland National Park, which is in the South Island.

This power station is the biggest hydroelectric plant in New Zealand. It can produce 850 MW of power. The Manapōuri Power Station is also famous for a big environmental protest called the Save Manapouri campaign. This campaign helped start the modern environmental movement in New Zealand.

The station was finished in 1971. Its main job was to provide electricity to the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter near Bluff, about 160 km away. Later, it also connected to the main power grid of the South Island. The station uses the 230-metre drop between Lake Manapōuri and Deep Cove, which is part of Doubtful Sound, 10 km away.

Building the station meant digging out almost 1.4 million tonnes of hard rock. This created the large machine hall and a 10 km tunnel for the water to flow out. A second, parallel tunnel was added in 2002 to make the station even more powerful. Since April 1999, the power station has been owned and run by Meridian Energy, a company owned by the New Zealand government.

Contents

Building the Power Station

The main part of the power station, called the machine hall, was dug out of solid granite rock. It sits 200 metres below the level of Lake Manapōuri. Two long tunnels, called tailrace tunnels, carry the water that has passed through the power station to Deep Cove. Deep Cove is a branch of Doubtful Sound, about 10 km away.

To get to the power station, workers and equipment use a two-kilometre vehicle tunnel. This tunnel spirals down from the surface. There is also a lift that goes down 193 metres from the control room above the lake. There are no roads directly to the site. Instead, a regular boat service takes power station workers 35 km across the lake from Pearl Harbour, a town at the southeast corner of the lake.

For many years, tourists could also take boat tours to see the power station. However, since 2018, these tours have been stopped for maintenance work. The original construction of the power station cost NZ$135.5 million. It took almost 8 million hours of work to build and sadly, 16 workers lost their lives during its construction.

Soon after the power station started working at full power in 1972, engineers found a problem. The water flowing through the first tailrace tunnel created more friction than expected. This meant the station couldn't produce as much power as it was designed to. For 30 years, until 2002, the station could only produce about 585 MW of power, much less than its planned 700 MW.

To fix this, a second tailrace tunnel was built in the late 1990s. This new tunnel is 10 km long and 10 metres wide. It was finished in 2002 and solved the problem. The second tunnel increased the station's power to 850 MW. It also made the water flow out more easily, allowing the turbines to make more power without using more water.

History of Manapōuri Power

Early Ideas for Power

The first people to explore and map this part of New Zealand noticed how much power could be made from the 178-metre drop between Lake Manapōuri and the Tasman Sea at Doubtful Sound. The idea of building a power station here was first thought of in 1903 by engineers Peter Hay and Lemuel Morris Hancock.

They saw that the lake system was very high above sea level, which was perfect for making electricity. Even though the area was very remote, they realised it would be great for big industrial projects, like making chemicals or metals. In 1926, a group of businessmen tried to get rights to use the water from Lake Manapōuri. They wanted to build a factory in Deep Cove to make nitrogen for fertiliser and weapons. However, they couldn't find enough money, and their plans didn't happen.

The modern story of Manapōuri began in 1955. A New Zealand geologist named Harry Evans found a huge amount of bauxite (a rock used to make aluminium) in Australia. In 1956, a company called Comalco was formed to develop this bauxite. Comalco needed a lot of cheap electricity to turn the bauxite into aluminium. They chose Manapōuri as the best place for this power and Bluff for the aluminium factory. The plan was to process the bauxite in Australia, ship it to New Zealand to be smelted, and then send the finished aluminium to markets.

Building Milestones

- February 1963: Bechtel Pacific Corporation won the contract to design and oversee the project.

- July 1963: Utah Construction and Mining Company and two local companies won contracts to build the tailrace tunnel and Wilmot Pass road. Utah Construction also won the contract for the powerhouse.

- August 1963: The ship Wanganella was brought to Doubtful Sound. It was used as a floating hotel for workers building the tailrace tunnel until December 1969.

- February 1964: Construction of the tailrace tunnel began.

- December 1967: The powerhouse was finished.

- October 1968: The tunnel was completed (called "breakthrough").

- September 1969: Water first flowed through the power station.

- September/October 1969: The first four generators started working.

- August/September 1971: The remaining three generators were started.

- 1972: The station was fully working. Engineers then found the problem with the tailrace tunnel's capacity.

- June 1997: Construction began on the second tailrace tunnel.

- 1998: A special machine called a tunnel boring machine started drilling from the Deep Cove end.

- 2001: The second tunnel was completed.

- 2002: The second tunnel started working. A $98 million project began to upgrade the seven generators. By the end of 2007, all seven generators were upgraded.

- 2014: Three large transformers were replaced. These were the biggest pieces of equipment to leave the station since it was built.

Political Decisions and Protests

In July 1956, the New Zealand Electricity Department announced the idea of building a power station using Lake Manapōuri's water. Five months later, Comalco officially asked the New Zealand government about getting a lot of electricity for aluminium smelting.

In 1960, the Labour Government and Comalco signed an agreement for Comalco to build both an aluminium factory at Tiwai Point and the power station at Manapōuri. This agreement went against the National Parks Act, which was supposed to protect the park. Comalco was given special rights to use the waters of both Lake Manapōuri and Lake Te Anau for 99 years. Comalco planned to build dams that would raise Lake Manapōuri by 30 metres and join the two lakes.

This plan led to the creation of the Save Manapouri campaign. This campaign marked the start of the modern environmental movement in New Zealand. In 1963, Comalco decided it couldn't afford to build the power station, so the New Zealand government took over. The electricity made by the plant was then sold to Comalco at a price that would help the government get back the cost of building the station.

In 1970, the Save Manapouri campaign organised a petition to Parliament. They were against raising the water level of Lake Manapōuri. The petition got 264,907 signatures, which was almost 10 percent of New Zealand's population at the time!

In 1972, a new Labour government was elected in New Zealand. The Prime Minister, Norman Kirk, kept his promise not to raise the levels of the lakes. He created a special group called the Guardians of Lake Manapōuri, Monowai, and Te Anau. This group was made up of leaders from the Save Manapouri Campaign and was set up to watch over how the lake levels were managed.

In 1984, the Labour Party came back into power. During this time, the government started selling off some government-owned businesses. Many people worried that the Manapōuri Power station would be sold, and Comalco seemed like the most likely buyer. In 1991, the Save Manapouri Campaign started up again, this time called Power For Our Future. They fought against selling the power station to make sure Comalco couldn't go back to its plans to raise Lake Manapōuri's water levels. The campaign was successful, and the government announced that Manapōuri would not be sold to Comalco.

On 1 April 1999, the New Zealand electricity system was changed. The Electricity Corporation of New Zealand was broken up, and Manapōuri Power Station was given to a new government-owned company called Meridian Energy.

In July 2020, Rio Tinto (the company that owned the aluminium smelter) announced they would close the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter in August 2021. This led to talks about what to do with all the electricity from Manapōuri. In January 2021, Rio Tinto decided to keep the smelter open until December 2024.

How the Power Station Works

The Manapōuri Power Station uses seven large Francis turbines to generate electricity. These turbines spin at 250 revolutions per minute. Each turbine is connected to a generator that produces 121.5 MW of power. The electricity is then sent through large transformers that change the voltage from 13.8 kV to 220 kV so it can travel long distances. There are eight transformers in total, with one kept as a spare.

The station's machine hall is 111 metres long, 18 metres wide, and 34 metres high. The first tailrace tunnel is 9,817 metres long and 9.2 metres wide. The second tailrace tunnel is 9,829 metres long and 10.05 metres wide. The road tunnel for access is 2,042 metres long and 6.7 metres wide. There are also seven cable shafts, each 1.83 metres wide and 239 metres deep, and a lift shaft that is 193 metres deep. The water flows into the turbines through seven penstocks, each 180 metres long.

Running the Station

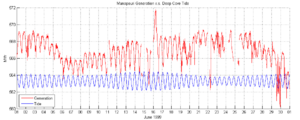

Because the tailrace tunnels are so long, it's hard to change how much power Manapōuri makes very quickly. Also, since the water flows out into Deep Cove at sea level, the amount of power produced can be affected by the ocean's tides. The difference between high and low tide can be up to 2.3 metres. This small change in water level can cause the power output to vary by about 5 MW. This means the power generation changes with the tides, not just with how much electricity people are using during the day.

Sending the Power Out

Manapōuri Power Station is connected to New Zealand's main power system, called the National Grid. It uses two sets of double-circuit 220 kV power lines. One set of lines goes from Manapōuri to Tiwai Point, passing through the North Makarewa substation. The other set connects Manapōuri to the Invercargill substation, with one circuit also going to North Makarewa. There's also another double-circuit 220 kV line that connects Invercargill to Tiwai Point.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |