Manchester computers facts for kids

The Manchester computers were a groundbreaking series of electronic computers. They were built by a small team at the University of Manchester between 1947 and 1977. This team was led by Tom Kilburn.

These computers were very special. They included the world's first computer that could store its own programs. They also created the world's first computer made with transistors. One of their computers was even the fastest in the world when it started in 1962!

The project had two main goals. First, they wanted to test a new type of computer memory called the Williams tube. This memory used special TV-like screens called cathode-ray tubes. Second, they wanted to build a machine to see how computers could help solve tough math problems.

The first computer in this series was the Manchester Baby. It ran its first program on June 21, 1948. This made it the world's first stored-program computer. The Baby and its improved version, the Manchester Mark 1, quickly caught the attention of the UK government. They asked a company called Ferranti to make a commercial version. This led to the Ferranti Mark 1, which was the world's first computer sold for general use.

The university later worked with a computer company called ICL. Many ideas from the university helped ICL design their 2900 series of computers in the 1970s.

Contents

What Was the Manchester Baby?

The Manchester Baby was built to test the Williams tube memory, not to be a full computer. Work on it started in 1947. On June 21, 1948, it successfully ran its first program.

This program had 17 instructions. It tried to find the largest number that could divide 262,144 (which is 218) without a remainder. It did this by checking every number downwards from 262,143. The program ran for 52 minutes and found the correct answer: 131,072.

The Baby was about 17 feet (5.2 m) long and 7 feet 4 inches (2.24 m) tall. It weighed almost 1 long ton (about 1,000 kg). It used 550 thermionic valves and needed 3.5 kilowatts of power. Its success was reported in a science magazine called Nature in September 1948. This showed the world it was the first stored-program computer. Soon, it was improved and became the Manchester Mark 1.

How Did the Manchester Mark 1 Develop?

Work on the Manchester Mark 1 began in August 1948. The goal was to give the university a more useful computer. In October 1948, a government scientist named Ben Lockspeiser saw a demonstration. He was so impressed that he quickly arranged for Ferranti to make a commercial version, the Ferranti Mark 1.

Two versions of the Manchester Mark 1 were made. The first one was ready by April 1949. The final version was fully working by October 1949. It had 4,050 valves and used 25 kilowatts of power. A key new feature of the Manchester Mark 1 was its use of index registers. These are common in modern computers today.

In June 2022, the "Manchester University "Baby" Computer and its Derivatives, 1948-1951" received an IEEE Milestone. This award celebrates important achievements in electrical engineering and computing.

What Were Meg and Mercury?

After building the Mark 1, the developers realized computers would be very useful for science. So, they started designing a new machine in 1951. This machine would have a floating-point unit, which helps with complex math.

The new computer ran its first program in May 1954. It was called Meg, or the "megacycle machine." It was smaller and simpler than the Mark 1. It was also much faster at solving math problems. Ferranti made a commercial version called the Ferranti Mercury. This computer used more reliable core memory instead of Williams tubes.

The First Transistor Computer

In 1952, while Meg was still being developed, a new project started. The goal was to build a smaller and cheaper computer. Two team members, Richard Grimsdale and D. C. Webb, worked on a machine using new transistors instead of valves. This became known as the Manchester TC.

At first, they only had germanium point-contact transistors. These were not as reliable as valves but used much less power. Two versions of this machine were built. The first one was a prototype and became the world's first transistorized computer. It started working on November 16, 1953. This 48-bit machine used 92 point-contact transistors and 550 diodes.

The second version was finished in April 1955. It used 250 junction transistors and 1,300 solid-state diodes. It only used 150 watts of power. However, it still used some valves for its clock and to read its magnetic drum memory. So, it wasn't the first *completely* transistorized computer. That honor went to the Harwell CADET in 1955.

Early transistors were not very reliable. This meant the machine often stopped working after about 90 minutes. Things improved when more reliable junction transistors became available. A company called Metropolitan-Vickers used the Transistor Computer's design for their Metrovick 950. They changed all the circuits to use junction transistors. Six Metrovick 950s were built, with the first one ready in 1956. They were used successfully for about five years.

Meet Muse and Atlas: The World's Most Powerful Computer

In 1956, the university began working on MUSE. This name came from "microsecond engine." The goal was to build a computer that could process one million instructions per second! A microsecond is one millionth of a second.

In late 1958, Ferranti joined the project, and the computer was renamed Atlas. Tom Kilburn led this joint effort. The first Atlas computer officially started on December 7, 1962. At that time, it was considered the most powerful computer in the world. People even said that when Atlas went offline, half of the UK's computer power was lost!

Atlas was incredibly fast. Its quickest instructions took only 1.59 microseconds to complete. It also pioneered many new ideas still used today. For example, it used virtual storage and paging. This allowed each user to have a huge amount of memory available. The Atlas Supervisor was its operating system, and many consider it the first modern operating system.

Two other Atlas machines were built. One was for a group of companies and the University of London. The other was for the Atlas Computer Laboratory near Oxford. A similar computer, called the Titan or Atlas 2, was built for Cambridge University. It had a different memory setup and used a time-sharing operating system.

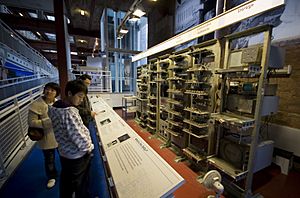

The University of Manchester's Atlas was turned off in 1971. However, the last Atlas computer was used until 1974. Parts of the Chilton Atlas are now kept at the National Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh.

In June 2022, the "Atlas Computer and the Invention of Virtual Memory 1957-1962" also received an IEEE Milestone.

What Was the MU5?

The Manchester MU5 was designed to be the next big computer after Atlas. Ideas for this new machine were discussed in 1968. The team wanted MU5 to be 20 times faster than Atlas!

In 1968, the Science Research Council gave Manchester University a grant of £630,466 (about £9.94 million today) to develop the machine. ICT (which later became ICL) also helped the university with their production facilities. At its busiest in 1971, about 60 people were working on the MU5 project.

The MU5 processor had special features to make it very efficient. It used associative memory to quickly find data. Its instructions were designed to help compilers create fast code. It could also predict what instructions would come next to speed things up.

The MU5 operating system, called MUSS, was very flexible. It could run on different processors. In the final MU5 system, three processors (MU5 itself, an ICL 1905E, and a PDP-11) were connected by a high-speed system. All three ran a version of MUSS.

MU5 was fully working by October 1974. Around the same time, ICL announced their new 2900 series of computers. The ICL 2980, first delivered in 1975, was greatly influenced by the MU5 design. The MU5 stayed in use at the University until 1982.

What Was the MU6?

After MU5 was finished, a new project started to create its successor, MU6. MU6 was planned to be a family of processors. This included MU6P for personal computers, MU6-G for general or scientific tasks, and MU6V for parallel processing.

A prototype of MU6V was built and tested, but it wasn't developed further. The MU6-G was built with a grant and worked as a service computer in the Department from 1982 to 1987. It used the MUSS operating system, which was first developed for the MU5 project.

What is SpiNNaker?

SpiNNaker stands for "Spiking Neural Network Architecture." It's a huge, manycore supercomputer architecture designed by Steve Furber at the University of Manchester. It was built in 2019.

SpiNNaker has 57,600 ARM9 processors. Each processor has 18 cores and 128 MB of memory. This means it has over 1 million cores and more than 7 TB of RAM! This powerful computer is based on spiking neural networks. These are very useful for simulating how the human brain works.

Summary of Manchester Computer Developments

| Year | University Prototype | Year | Commercial Computer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Manchester Baby, which evolved into the Manchester Mark 1 | 1951 | Ferranti Mark 1 |

| 1953 | Transistor computer | 1956 | Metrovick 950 |

| 1954 | Manchester Mark II a.k.a. "Meg" | 1957 | Ferranti Mercury |

| 1959 | Muse | 1962 | Ferranti Atlas, Titan |

| 1974 | MU5 | 1974 | ICL 2900 Series |