Manuel Foster Observatory facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

|

|||||

The Observatorio Manuel Foster, also known as the Manuel Foster Observatory, is an astronomical observatory built in 1903 on Cerro San Cristóbal near Santiago, Chile. It was first called the D. O. Mills Observatory after the generous person who funded it, Darius Ogden Mills.

This observatory was created as a branch of the Lick Observatory to study stars in the southern part of the sky. Under the guidance of American astronomer W. W. Campbell, it was used for a big project to figure out the direction the Sun moves through space.

The first money for the project covered two years of work. Because Campbell was badly hurt, his assistant, William H. Wright, led the expedition. After setting up the telescope and its dome, they found the equipment worked well. Observations started in late 1903. By October 1905, they had successfully collected 800 spectrograms, which are like special photos of starlight.

Heber D. Curtis took over in March 1906. New funding from Mills helped improve the observatory. Using the information gathered here, Campbell finished his study on the Sun's motion in 1926. With more money, the observatory kept working until 1928. Then, a Chilean lawyer named Manuel Foster Recabarren bought it and gave it to the Universidad Católica de Chile.

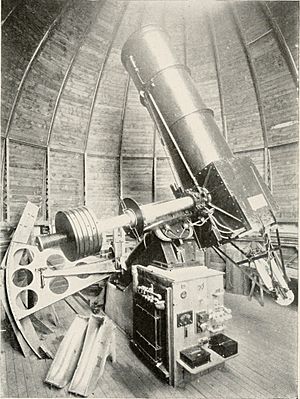

Today, the observatory is located in the Santiago Metropolitan Park. It became a national monument in 2010. Its main telescope is a cassegrain reflector. It has a 0.93 meter (about 3 feet) wide opening and an equatorial mount, which helps it track stars. This telescope is housed inside a dome that can spin around.

Contents

How the Observatory Began

In 1897, astronomer William Wallace Campbell and his assistant, William H. Wright, started a project. They wanted to measure the speed of all bright stars in the northern sky. They used a new tool called the Mills spectrograph. This tool was attached to the 91 centimeter (36 inch) telescope at the Lick Observatory.

This spectrograph was made possible by a grant from banker Darius O. Mills. It was designed to photograph the light from stars, called stellar spectra. It started being used in May 1895 and worked very well. It made measurements much more accurate than before.

By 1894, Campbell realized they needed to do the same measurements for stars in the Southern Hemisphere. This would help them better understand how our Solar System moves compared to nearby stars. When the director of Lick Observatory died in 1900, Campbell took his place. He told D. O. Mills about the need for a southern observatory, and Mills agreed to pay for it.

Mills provided $26,075 for instruments, buildings, salaries, travel, and supplies for a two-year trip. The new observatory was planned to be a simpler version of the Lick Observatory's equipment for studying starlight. Campbell first thought about Australia for the location. But weather records showed that Chile would be a better spot. He chose a place near Santiago, Chile's capital, so supplies and housing would be easy to find.

Building the Telescope and Dome

The Lick Observatory had a spare 36.25-inch (92 cm) silvered parabolic glass mirror. But its shape wasn't perfect. After deciding on a Cassegrain-style reflecting telescope, they sent the mirror to the John A. Brashear Company in Allegheny in 1901 to be reshaped.

However, the mirror broke while a central hole was being cut. So, they had to order a new one. The telescope's base was built in Los Angeles and arrived at the observatory in December 1901. A spinning steel dome for the observatory was built by Warner and Swasey Company. The spectroscope and other parts were made by Brashear.

When the new mirror arrived in 1902, its shape was still wrong, and it had to be sent back for fixing. Because of these delays, they decided to ship the instruments to Chile without fully testing them first. The finished mirrors finally arrived in February 1903. As a result, the team reached Chile in April, which was the start of the southern rainy season.

Setting Up and First Observations

W. W. Campbell had planned to go on the trip himself. But he was badly injured while testing the equipment. So, Campbell's assistant, William H. Wright, led the trip with Harold K. Palmer as his helper. They sailed from San Francisco on February 28, 1903. They arrived in Valparaíso on April 18.

After a month-long delay due to a port strike, the equipment was unloaded. It was then moved 120 miles (193 km) to Santiago by train. Members of the Chilean government welcomed them, as they had agreed to help.

After looking for a good spot, they chose the middle part of Cerro San Cristóbal for the observatory. This hill is in the northeastern suburbs of Santiago. It is about 860 feet (262 meters) above the city. This height put it above the city's dust and haze. It was also free from the frequent fogs in the valley. The temperature range on the mountain was also better.

Unfortunately, the weather was unusually cloudy that year, which limited their tests. In late May, the strike ended in Valparaíso. This allowed the observatory equipment to be shipped, and construction began.

The telescope had only minor damage during shipping. However, the dome arrived very rusty and needed repairs. Building the observatory started on May 27. The dome had a steel frame covered with wood and heavy painted canvas. This covering did not keep water out. The observers lived in the city, so they had to climb to the observatory every night.

Testing of the main telescope began on September 11, 1903. They found some minor issues with the mirror's shape, but these were not a big problem for their work. The telescope also changed its focus as it cooled down. The silver coating on the mirror quickly became dull, which meant they needed longer exposure times. But the spectrograph worked as accurately as the one at Lick Observatory. By June 1, 1904, they had collected 380 successful spectrograms.

Continued Funding and Improvements

The first funded observation program ended in October 1905. By then, they had taken pictures of the light from brighter stars in the southern sky. They had a list of 145 stars, with at least four photographic plates taken for each. In total, they had 800 spectrograms. They also found 22 stars whose speeds were changing.

Mr. Mills agreed to keep funding the station for another five years. To lead this new period, astronomer Heber D. Curtis sailed from San Francisco on December 30, 1905. The same month, Palmer returned to Lick Observatory to start measuring the spectrogram plates. Curtis took charge on March 1, 1906, and Wright returned to the United States. Curtis's assistant, George F. Paddock, arrived on August 2, 1906.

The new money was used to improve the observatory. They built an extra building for a machine shop and two rooms for the observers. New parts were added to the telescope's declination axis, which had been hard to move. They also built two new spectroscopes for studying fainter stars. A cooling unit was added to keep the dome chilled in the evening. They also built a device to quickly put new silver on the mirror.

The first time they resilvered the mirror was in March 1906. After this, they could take pictures 40% faster. However, the new silver coating only lasted about a month before it became dull again. They decided it should be resilvered every two months for the best results. The leaky canvas roof of the dome was replaced with galvanized iron in early 1906.

Data collection continued for the next three years. About 200 nights each year were good for viewing. Most of the work used the two-prism spectroscope, which could see stars up to about magnitude 7.0. By late 1909, they had produced 2,700 photographic plates. They found 48 possible spectroscopic binaries (star systems where two stars orbit each other very closely). They also found several stars moving very fast across the sky. In February and March 1909, the telescope was used to observe Comet Morehouse.

On June 5, Joseph H. Moore arrived in Santiago to take charge of the observatory. Curtis left for California on June 17, and Paddock left in July. Roscoe F. Sanford replaced Paddock. By early December, they had taken, measured, and collected data for 725 stars. In total, they had made 3,608 spectrographic plates.

Later Years and New Ownership

After D. O. Mills died in 1910, his son, Ogden Mills, agreed to fund the observatory until 1913. He provided $30,000, which covered costs until 1914. Besides normal measurements, Campbell decided to use the extra time to measure the light from nebulae (clouds of gas and dust) in the southern sky. This would add to earlier measurements of 13 nebulae in the northern sky.

Observations of 12 nebulae in the Greater Magellanic Cloud showed that this formation was moving away at a speed of 250 to 300 kilometers per second (155 to 186 miles per second). This suggested it might be related to spiral nebulae. After four years in charge, Moore returned to California in 1913. Ralph E. Wilson replaced him on August 1 of that year. Sanford stayed for two more years, leaving in June 1915.

Full funding from Ogden Mills ended in 1917. The remaining time was paid for by fourteen friends of the observatory, including Mills. Wilson was helped by math instructor Arthur A. Scott from 1913 until June 1917. Then Charles M. Huffer helped. In June 1918, Wilson left and returned to the United States. He worked on building aircraft for the United States in World War I. This left Huffer alone at the station. Paddock was not allowed to return by the military. Huffer ran the station until October 1919, when Paddock returned for five years. The observatory was renamed the Chile Station of Lick Observatory in 1919. The last head of the observatory was Ferdinand J. Neubauer, who took over on January 22, 1924.

In 1926, Campbell was able to figure out the speed and direction of the Sun's motion based on the star speed study:

| V0 | 19.6 ± 0.40 km/s |

| α0 | 271.5 ± 1.40° |

| δ0 | +28.6 ± 1.17° |

This location is in the constellation of Hercules. It is close to today's estimated position of (α = 271°, δ = 30°) and a speed of 19.7 km/s. The observatory continued to operate under Lick Observatory control until 1928. About 10,700 spectrograms were produced. The results from both hemispheres were published at that time.

The Chilean lawyer Manuel Foster Recabarren bought the observatory in 1928. He then gave it to the Universidad Católica de Chile. At that time, it was the biggest working telescope in the southern hemisphere. It was also the tenth largest in the world.

During the 1940s, German astronomer Erich P. Heilmeier used it to study Beta Cephei and other variable stars. As the city of Santiago grew, the conditions for observing got worse. Part of the observatory was damaged in a fire. Heilmeier also complained about a lack of water, astronomers, and money. The University kept using it sometimes until 1948. Then, technical and money problems caused it to stop working.

Restoration of the observatory began in the 1980s. Since 1982, the University has used it again for research and teaching. They focused on studying RS CVn variables, Wolf–Rayet stars, and Beta Cephei stars. In 1986, they observed Halley's Comet for the public. Then, in 1984, they observed the supernova SN 1987A. However, the quality of observations got worse over time because of the city's growth and its light pollution. The observatory stopped working completely in 1995. It was declared a national monument in 2010. The site is now mainly used for education. It is open for guided tours for the public.

See also

In Spanish: Observatorio Manuel Foster para niños

In Spanish: Observatorio Manuel Foster para niños

- List of astronomical observatories

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |